Introduction

The goal of the poultry breeding industry is the production of healthy chicks, which will be viable from both an immunological and nutritional perspective, when placed in the production setting. Communication and shared responsibility between the breeder farms and hatchery are essential to minimize the risk and consequences of health problems.Good rearing management is the starting point for healthy, productive and profitable hatching egg production. Rearing management means all factors which influence the birds’ health and includes several factors such as house structure, climatic conditions (ventilation, temperature, litter condition), stocking density, feed and water supply, hygienic conditions as well as the qualification and knowledge of the stockman. These factors affect each other and can promote or inhibit the health condition of the flock. In aiming to achieve desired performance results, managers of breeder flocks should integrate good environment, husbandry, nutrition and disease control programs. The rearing management must be directed to satisfy the bird’s requirements, to promote the production and to prevent diseases. Any disturbance can cause stress, which will reduce the resistance of the birds, increase their susceptibility to infections and reduce their immune response to vaccines.

Infectious poultry diseases are often associated with severe economic losses. Many of these diseases, re-emerging or introduced into a geographic area, can explode into an epidemic and may significantly affect international trade. Early recognition and monitoring programs are essential in managing infections and minimizing their economic impact.

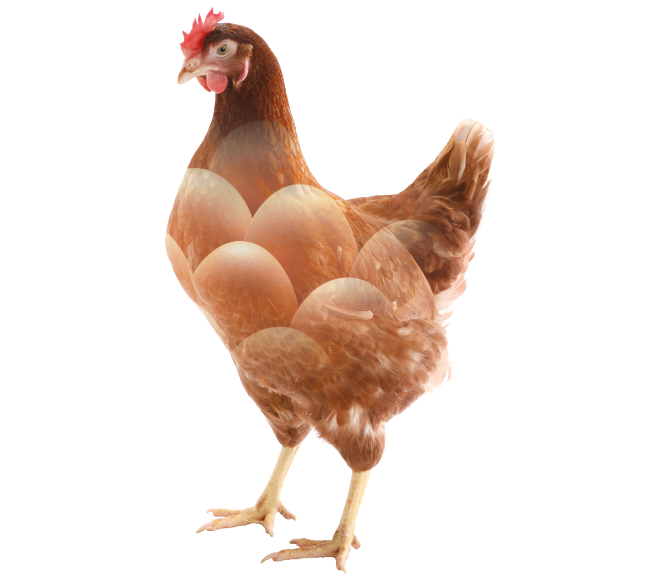

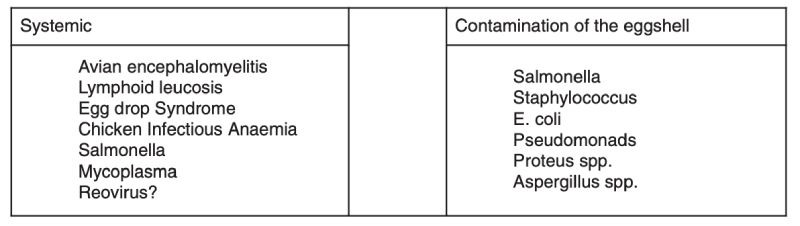

Infectious agents can be introduced into and spread among breeder farms by different routes. All infectious agents are transmitted horizontally (laterally) by direct contact between infected and noninfected susceptible birds or through indirect contact with contaminated environments through ingestion or inhalation of organisms. In addition, infections can occur via contamination of feed, water, equipment, environment and dust. Significant reservoirs for micro-organisms are man, farm animals, pigeons, water fowl and wild birds. Rodents, pets and insects are also potential reservoirs and transmit the infection between houses and can contaminate stored feed. Further sources are “carrier” birds who continue to excrete the infectious agent after they recover and no longer show clinical symptoms of the disease. Contaminated material can also be picked up on shoes and clothing and carried from an infected to a healthy flock. The disease can be spread by vaccination and beaking trimming crews, manure haulers, drivers of rendering trucks and feed delivery personnel. Vertical transmission occurs primarily by systemic ovarian transmission, by passage through the oviduct or by contact with infected peritoneum or air sacs. Secondly, vertical transmission happens by contamination of the egg content as a result of faecal contamination of the eggshell in contaminated nests, floor or incubators with subsequent penetration into the eggs (Fig. 1).

Disease prevention and control

Control measures to prevent introduction and spread of infections in breeder flocks should be concentrated on high standards of poultry husbandry with bacteriological and serological monitoring of breeding birds. These measures must be coupled with meticulous attention at all stages of hatching egg production. The general strategy to control infectious poultry diseases includes:

- eradication of vertically transmitted diseases from top to bottom – initiated by the primary breeder and pursued down to the commercial producer;

- hatchery hygiene and hatching egg sanitation as well as education programs and regular bacteriological examination of employees; and

- hygienic measures throughout the production chain, vaccination, therapy, decontamination of feed. Efforts of the industry to improve bio-security may be supported or even enforced by legislation.

Figure 1: Some possible egg-borne infections

Hygienic measures

It is vital that hygienic standards in the breeder house are impeccable to avoid infection entering the hatchery either within or on the shell of the eggs. The design of the house is usually based on the production objective and focused on efficient production of hatching eggs. The design and construction of breeder houses should also focus on easy management, maintenance, and application of effective hygienic measures. Poultry houses should be kept locked and no visitors allowed to enter. Further precautions related to staff should be taken. Regular bacteriological examinations must be performed to identify carriers and to prevent transmission and cross contamination on the farm. Cleaning, disinfection and vector control must be integrated in a comprehensive disease control program. The procedure should be tailored to meet the particular needs. The cleaning and disinfection program should include time schedule, type of disinfectant and concentration as well as microbiological monitoring of the procedures. The procedures should be established not only for cleaning and disinfecting the house and surfaces but also for cleaning and disinfection of the equipment, which is itself used for cleaning. Rodents, especially rats and mice, are particularly important sources of salmonella contamination of poultry houses. An intensive and sustained rodent control is essential and needs to be well planned and routinely performed and its effectiveness should be monitored. Household pets also constitute a serious hazard. Buildings therefore should be pet proof.

In breeder farms it is important to optimize the production of clean fertile hatching eggs, by keeping egg laying areas as clean as possible, including the nest litter or pads. In addition, the breeder house nesting should be inspected on a regular basis. Hatching eggs should be collected frequently (3-4 times daily) to minimize the time that they are exposed to a contaminated environment. All substandard eggs with misshapen, cracked or thin shells should be removed. The egg shells should be disinfected soon after collection on the farm, since the penetration of the shell by micro-organisms is particularly rapid. If the bacteria penetrate the shell before the egg reaches the hatchery, it is difficult to find an effective method to counteract such contamination.

Two methods are used to disinfect hatching eggs under field conditions, namely fumigation or dipping in a solution of detergent or disinfectant. Fumigation is done best with formaldehyde gas for at least 20 minutes with a concentration of 35 ml formalin mixed with 17.5 g potassium permanganate and 20 ml water per m³ space. Temperature during fumigation must be maintained at a minimum of 20-24°C and relative humidity at 70%. The eggs should be placed in trays that will permit the fumigant to contact as much of the shell surface as possible. Because of the unpleasant nature of formaldehyde gas and its possible health hazards to the operator, some owners elect to use wet treatments. Different sanitizing solutions are used and most of them are based on chlorine, glutaraldehyde or quaternary ammonium compounds. Egg dipping in detergents or in disinfectants is highly effective in greatly reducing or eliminating the bacteria from the shell when performed correctly. However, there is little or no effect on those bacteria that have already penetrated the shell. Manufacturer’s instruction for the chemicals used should be followed, particularly those concerning the number of eggs that may be dipped per liter solution and how often fresh solution has to be provided. Attention also must be directed to the temperature of the detergent which must be higher than the egg temperature. After hatching egg sanitation, hygienic measures should be followed to preclude recontamination. Farm egg rooms should have a guideline for cleanliness and standard operation. Bacterial contamination in the egg room should be routinely monitored.

Vaccination

Vaccination is one of the most effective tools to prevent specific diseases. Several factors are dictating the choice of the vaccine, vaccination route and frequency of vaccination. These factors are: the epidemiological situation, the type of production, management practices on the farm, the goal of vaccination, availability of the vaccine, cost benefit analysis, general health status of the flock and governmental regulations. Vaccination programs for breeder flocks should be tailored to induce long lasting high antibody levels during the entire production cycle in order to protect against possible field challenge, to maintain acceptable standards of egg production, egg quality and hatchability, and to transfer the desired maternal antibodies to the offspring.

Treatment

In spite of all precautions, poultry may become sick. In such cases rapid medication is essential. Several drugs have been found useful for reducing clinical signs and shedding of some bacterial diseases in infected flocks. Treatment should reduce losses, but in some cases relapses may occur when treatment is discontinued. No drugs should be given until a diagnosis has been obtained; giving the wrong drug can be a waste of money. Drugs should be used very carefully: the correct dose level and duration is important. It should also be kept in mind that residues of drugs in fertile eggs from treated breeders may occasionally cause abnormalities in some embryos.

Eradication by industry and legislation

Salmonellosis and salmonella infections in poultry are distributed world-wide and result in severe economic losses when no effort is made to control them. The large economic losses are caused by high mortality during the first four weeks of age, high medication costs, and reductions in egg production in breeder flocks, poor chick quality and high costs for eradication and control measures. The most important aspect, however, is the effect of salmonella contaminated eggs, poultry meat and meatproducts on public health.

Salmonella belong to the family Enterobacteriaceae and all members are Gram-negative, non-sporing rods without capsules. The genus Salmonella includes about 2500 serovars. Some serovars may be predominant for a number of years in a region or country, then disappear to be replaced by another serovar. The course of the infection and the prevalence of salmonellosis in poultry depend on several factors such as: salmonella serovar involved, age of birds, infectious dose and route of infection. Further, stress-producing circumstances such as bad management, poor ventilation, high stocking density or concurrent diseases may also contribute to the development of a systemic infection with possibly heavy losses among young birds. After recovery, birds continue to excrete salmonella in their faeces. Such birds must be considered as a potential source for transmission of the microorganisms. The incubation periods range between 2 and 5 days. Mortality in young birds varies from negligible to 10 – 20% and in severe outbreaks may reach 80% or higher. The severity of an outbreak in young chicks depends on the serovar involved, virulence, degree of exposure, age of birds, environmental conditions and presence of concurrent infections.

If infection was egg transmitted or occurred in the incubator, there will be a lot of unpipped and pipped eggs with dead embryos. Symptoms usually seen in young birds are somnolence, weakness, drooping wings, ruffled feathers and huddling together near heat sources. Many birds that survive for several days will become emaciated, and the feathers around the vent will be matted with faecal material. Furthermore respiratory distress as well as lameness as a result of arthritis may be present. Adult birds serve mostly as intestinal or internal organ carriers over longer periods with little or no evidence of the infection.

In general the main strategy for control of microbial food borne hazards should include: Cleaning the production pyramid from the top (in the case of invasive salmonella) by destroying infected flocks, hatching egg sanitation and limiting introduction and spread at the farm through Good Animal Husbandry Practices. Reducing salmonella colonization by using feed additives, competitive exclusion treatment or vaccines offer additional possibilities.

In 1992, the European Union adopted a directive to monitor and control Salmonella infections (Directive 92/117/EEC) in breeding flocks of domestic fowl. This directive laid down specific minimum measures to control the infection. Those focused on monitoring and controlling salmonella in breeding flocks of the species Gallus gallus, when serotypes Salmonella Enteritidis or Salmonella Typhimurium were detected and confirmed in samples taken.

The Scientific Committee on Veterinary Measures relating to Public Health considered that the measures in place to control food-borne zoonotic infections were insufficient at that time. It further considered that the epidemiological data collected by Member States were incomplete and not fully comparable. As a consequence, the Committee recommended to improve the existing control systems for specific zoonotic agents. Simultaneously, the rules laid down in Directive 2003/99/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 November 2003 on the monitoring of zoonoses and zoonotic agents, amending Council Decision 90/424/EEC and repealing Council Directive 92/117/EEC, replaced the monitoring and data collection systems established by Directive 92/117/EEC and Council Regulation 2160/2003/EC on the control of salmonella and other specified food-borne zoonotic agents was adopted. This Regulation covers the adoption of targets for the reduction of the prevalence of specified zoonoses in animal populations at the level of primary production. After the relevant control program has been approved, food business operators must have samples taken and analyzed to test for the zoonoses and zoonotic agents. On 30 June 2005 the Commission issued Regulation (EC) No 1003/2005 implementing Regulation (EC) No 2160/2003 as regards a Community target for the reduction of the prevalence of certain salmonella serotypes in breeding flocks of Gallus gallus and amending Regulation (EC) No 2160/2003. The Community target for the reduction of Salmonella Enteritidis, Salmonella Hadar, Salmonella Infantis, Salmonella Typhimurium and Salmonella Virchow in breeding flocks of Gallus gallus shall be a reduction of the maximum percentage of adult breeding flocks remaining positive to 1 % or less by 31 December 2009. Details of European legislation to control Salmonella and other zoonotic diseases is dealt with in detail by Voss (2007) in this issue of Lohmann Information.

Avian Mycoplasmosis

Mycoplasmas have affected the industry for many years and effective control of Mycoplasma infection has been a fundamental stepping-stone to improved performance and productivity. However, infections appear to be making a comeback. Numerous species of mycoplasmas have been isolated from avian sources. Two species are recognized as predominantly pathogenic to chickens and turkeys. Mycoplasma gallisepticum (MG) affects the respiratory system and is referred to as chronic respiratory disease (CRD) in chickens, and infectious sinusitis in turkeys. Mycoplasma synoviae (MS) may cause respiratory and/or joint diseases. Two additional species are known to be pathogenic to turkeys. Mycoplasma meleagridis (MM) causes airsacculitis, and Mycoplasma iowae (MI) causes decreased hatchability.

The disease spreads from flock to flock by vertical transmission through infected eggs. Infected progeny then transmit the agent horizontally either by direct bird-to-bird contact or by indirect contact through contaminated feed, water and equipment. Concerning vertical transmission, hens which become infected before the onset of lay tend to transmit at a lower rate than hens initially infected during egg production. Generally egg transmission is intermittent and the rate is variable (1-10%) and very low. The spread of infection from bird to bird within one pen is usually rapid, but it is rarely transmitted from one house to another. However, in continuous production complexes (multiple-age) with chronic apparently healthy carriers the spread of infection is difficult to control since the cycle of infection can not be broken without complete depopulation. The agent also can be transmitted by other species of birds as well as mechanically by other animals and man.

The clinical signs and the course of the disease are influenced by several factors such as the presence of concurrent micro-organisms (such as TRT, Influenza, Reo and E.coli) and/ or improper management (increased dust and ammonia levels in the environment).

Eradication of Mycoplasma in breeder flocks through testing and slaughter is the preferred method to clean the production chain from the top and to prevent mycoplasma introduction through primary and commercial breeder flocks. However, in places with intensive continuous poultry production it has been determined that this method is too expensive and impractical. Hatching egg treatments with antibiotics for the control of egg transmitted bacterial pathogens has been widely investigated and seems to be of great value. Different methods of egg treatment have been used such egg dipping in antibiotics using pressure differential dipping or temperature differential dipping. These methods greatly reduce the mycoplasma egg transmission, but do not always completely eliminate it.

Dipping solutions can become excessively contaminated with resistant micro-organisms such as pseudomonads and organic material. To prevent bacterial contamination of the solution filtering with subsequent cool storage and/or addition of disinfectants is the most effective method. Thorough and continuous bacteriological monitoring of dip solution is also required. The concentration of the antibiotics must be examined regularly and renewed routinely. By using enrofloxacin the pH-value of the dipping solution can be corrected during storage. The use of egg dipping in antimicrobials should be critically evaluated, because of the irregular uptake of dip solution, uneven distribution of active substance in the egg compartments and lack of standardization in dipping technique. Additionally, it is known that different disinfectants used for washing can influence negatively the antibiotic uptake of hatching eggs. Therefore it is recommended that the compatibility of different disinfectants used for egg washing and/or used in dipping solution has to be examined before application. As the uptake of active substance by the hatching egg can be very irregular during dipping, individual egg injection with accurate delivery of the proper dose is preferred in elite and grandparent breeding stock. Automated systems for in ovo drug disposition before hatch can also be used.

Hatchery management

Hatcheries must be designed to permit only a one way flow of traffic from the egg entry room through egg trays, incubation, hatching and holding rooms to the van loading area. The ventilation system must prevent recirculation of contaminated air. Hatching eggs should be from known sources to ensure that the origin of eggs is traceable. Do not incubate floor eggs, cracked eggs or eggs with hairlines. All eggs should be sanitized on arrival at the hatchery (pre-setting treatment) using fumigation. Additionally fumigation can be carried out after setting. This provides a final disinfection following handling, transport and risks of environmental contamination during storage of hatching eggs.

Good hatchery practice includes the analysis of unhatched eggs on a regular basis and, if infections are found, to trace the sources. Sanitation in the hatchery is paramount to the future health of chicks and poults. Cleaning and disinfection of machines and rooms must be carried out regularly. Hatchery equipment must be free of all organic matter before disinfection to ensure that the hatchery sanitation program is fully effective. Fluff samples from various surfaces in the hatchery should be cultured to detect microbial populations in hatchery air. The health status of all employees, including chick sexers, should be regularly monitored.

Education programs

The success of any disease control program depends on all people with direct or indirect contact with hatching eggs or chicks. It is essential to incorporate education programs about micro-organisms, modes of transmission as well as awareness of the reasons behind such control programs by people involved in poultry production.

Conclusions

Disease conditions are mostly accompanied with heavy economic losses in the poultry industry. Breeder farms and hatchery should be considered as an integrated operation. Close communication between breeder farm and hatchery is essential in sharing responsibility. Goals set for hatching egg production, hatchability and chick quality can only be reached with healthy breeder flocks. Good management practices, focused on the health and performance potential of day-old chicks, includes monitoring all breeder flocks and hatchery hygiene on a regular basis. Traceability of each batch of chicks or poults from hatchery to breeder farm helps to detect the source of problems and their elimination.

can be obtained from the author.

Zusammenfassung

Bruteierlieferbetriebe und Brüterei in gemeinsamer Verantwortung für die Produktion von Qualitätsküken

Wirtschaftliche Produktion von Geflügelfleisch und Eiern beginnt mit gesunden und leistungsfähigen Eintagsküken. Auf deren Produktion sind Brütereien spezialisiert, die wiederum von der Lieferung von Bruteiern definierter Qualität aus spezialisierten Bruteierlieferbetrieben abhängen. Die hierarchische Gliederung in der modernen Geflügelproduktion in Zucht-, Vermehrungs- und Produktionsbetriebe erleichtert die systematische Eradikation vertikal übertragbarer Krankheitserreger und den Informationsaustausch über die jeweils verfügbaren Möglichkeiten, die horizontale Übertragung von Erregern zu unterbinden. Die Geflügelindustrie hat aus eigenem Interesse erhebliche Fortschritte in der Kontrolle von Geflügelkrankheiten erreicht. Gesetzliche Vorgaben der EU sollen dazu beitragen, die Lebensmittelsicherheit in den Mitgliedsstaaten weiter zu verbessern und insbesondere das Risiko von Salmonellosen und anderen Zoonosen zu begrenzen. Integrationen bzw. feste Verträge zwischen Brütereien und Bruteierlieferbetrieben helfen, die Verantwortung zu definieren und konsequent auf vereinbarte Ziele hinzuarbeiten.