Summary

This review calls attention to management factors which need special attention to optimize results

under conditions of non-cage management, starting with rearing in a technical environment similar

to the production unit and including optimal nutrition, health care and husbandry.

Introduction

The trend away from conventional battery cages towards deep litter, perchery and free range housing systems for laying hens has intensified in recent years. In West European countries in particular laying hens are increasingly kept in production systems that are consistent with ethical and moral principles of these societies. Organic farms managed in accordance with specific guidelines for organic farming are also gaining market shares.The management of laying hens in deep litter, perchery and free range systems requires more expertise and time than conventional battery cages. Any farmer who decides to keep hens in these production systems should try to learn as much as possible from well-managed and successful operations.

The management recommendations, most of which have been followed since many years in the management of layer and broiler parent flocks, draw on results of scientific studies as well as field experience and should help poultry farmers to optimize results under their specific conditions.

Design of laying houses

The first step in planning to build new houses or converting existing buildings to deep litter or percheries is to consult experts with sufficient experience. The construction of deep litter and perchery housing has to meet different and often higher standards than cage housing. Since the birds spend at least part of the time directly on the floor, this must be well insulated. The lower stocking density per m² of floor space compared with conventional cages and the corresponding reduction in heat production by the hens must be taken into account when designing ventilation and air-conditioning installations.The dispersion of the hens within the building depends on its size, any compartments within the shed, but especially air flow and house climate. If the latter two factors are relatively uniform the hens will disperse evenly within the shed and feel comfortable. Otherwise the birds will crowd together in areas of the shed they find agreeable.

Nests must be easily accessible and preferably positioned in a central location in the laying house. To train hens to use the nests, all eggs laid on the litter floor must be picked up frequently to discourage other hens from using these “floor nests”. Possible reasons for preferring certain floor positions should be analyzed to make them less attractive. Eggs laid outside the nest are hygienically compromised and have to be marketed at discounts.

In deep litter or perchery housing dust is generated by hens using the scratching area and moving about. To minimize health hazards for the birds, a good ventilation of the shed is essential. If the deep litter house or perchery is combined with an outdoor enclosure, the building should be in a northsouth direction to keep the walls from heating up at different rates and different amounts of light entering the building when the popholes are open. The design of the building and its installations should be user-friendly to allow easy servicing.

Deep litter housing systems for laying hens vary in design and layout depending on the type of building. The classic form consists of 80-90 cm high dropping pits covered with wooden or plastic slats or wire mesh, which take up two-thirds of the floor space. Feeders, drinkers and nests should be positioned on top of the dropping pit and the drinkers mounted at a distance of 30 to 50 cm directly in front of the nests.

The litter area with sand, straw, wood shavings or other materials occupies about one-third of the floor space and allows the hens to move about, scratch and dust-bathe. The littered scratching area may be replaced by perforated flooring. In this case it is recommended to provide a winter garden where the birds can express their natural behaviors such as scratching and dust-bathing. Stocking densities should not exceed 9 hens per m² of usable floor space. Rails or other elevated perching facilities should be provided as resting places for the hens.

Percheries are systems where the birds can roam on several levels. All levels are covered with wooden or plastic slats or wire mesh and may have ventilated manure belts installed. Feeding and watering facilities are usually located on the lower tiers, while the upper tiers serve as resting areas. Depending on the perchery type, the laying nests are either within the system or outside the perchery. A stocking density up to 18 hens per m² floor area is permitted. Lighting programs and feeding times can be designed to encourage the birds to move around the different levels. When constructing a new facility, the house carcass and the perchery system will be designed to match; when existing buildings are to be equipped with a perchery system, the adaptability must be taken into account. In free range systems a normal deep litter house or perchery is combined with an outdoor enclosure (4 m² floor area per hen) for the hens. This facility must be available to the birds during the day.

Popholes along the entire length of the building provide access to the exterior. A winter garden attached to the poultry house has proved highly beneficial. The hens cross the winter garden to get to the outdoor enclosure. Winter gardens in front of the laying house have a positive effect on both litter quality and house climate: when the popholes are opened, cold air does not flow straight into the building and the indoor temperature is less affected than without a winter garden.

Requirements for pullets

Pullets destined for deep litter or perchery housing should be reared in comparable management systems. This ensures minimal stress during transfer, the birds settle down quickly in their new surroundings and production can start without problems.Pullets to be housed in alternative systems should have their beaks carefully treated. Without proper beak treatment, injurious picking may develop any time during the laying period. Geneticists at Lohmann Tierzucht have been selecting against cannibalism and feather pecking for many years, but as long as these behaviors are observed in commercial farms, beak treatment is recommended in accordance with legal requirements. Egg producers should discuss their preferences with the pullet supplier in good time.

The bodyweight of the pullets should preferably be above the breeder’s standard. A slight overweight gives the birds a reserve during the transfer phase. When weighing pullets on arrival, the fasting loss during transit must be taken into account. Since birds kept on litter floors and in percheries have approx. 10 %, with free range even +15 %, higher energy requirements for maintenance, the pullets must have learned to eat more than birds in conventional battery cages. The ability to consume sufficient feed soon after arrival in the laying facility is of paramount importance for the hens.

The more closely the growing facility resembles the production system, the easier it will be for the pullets to adjust to their new surroundings. Hens in floor housing and percheries must also be able to move around by flying and jumping. To learn these skills, facilities like rails or perches should be provided before the age of six weeks. In deep litter systems suspended feeder chains have proved effective.

In percheries it is important to ensure that the levels are opened before the chicks are six weeks old. Staggered feeding times on the different levels encourage the pullets to move around within the building.

Housing of pullets

Pullets should be transferred to laying houses in good time before the anticipated onset of production. The recommended age is 17 or 18 weeks. The move from the grower to the layer facility should be handled with care but speedily. Capture, transportation and vaccination are stressful to the hens. Gentle transfer and careful adaptation of the flock to the new surroundings are crucial for good production results. After transfer the hens should be dispersed evenly in the laying quarters and placed close to feeders and drinkers. Water and feed must be available immediately.On arrival the light should be left on long enough so that the hens find their way around. Room temperatures should be within a comfortable range for the birds. They should not be disturbed during the first 24 hours after the move. Inspections should only be carried out in an emergency. The attendants should always be calm and quiet and wear the same clothing. If birds appear nervous, hyperactive attendants may be a cause.

Management during the early days

During the first few days after housing it is important to stimulate feed intake, e.g. by- Providing an attractive meal type ration with good structure

- Running the feeding lines more frequently

- Feeding when the trough is empty

- Lighting of feeding installations

- Moistening the feed

- Use of skim milk powder or whey-fat concentrate

- Vitamin supplements

Pullets should never lose weight after transfer. They should continue to gain weight, or at least maintain their bodyweight. If possible without exceeding reasonable stocking density, the hens should be confined above the dropping pit or the perchery until they reach approximately 75 % production. Light sources should be placed so that the entire building and the nest entrances are well lit. Only the light above the dropping pit or in the perchery should be on toward the end of the light day.

Litter

Type and quality of the litter are important for the hens and the house climate. Different materials may be used:- Sand or gravel up to 8 mm granule size

- Wood shavings

- Wheat, spelt, rye straw

- Bark mulch

- Coarse wood chips

Sand and gravel should be dry when put down. Wood shavings should be dust-free and not chemically treated. Straw must be clean and free of mold. A litter depth of 1-2 cm is sufficient. Litter should be put down after the hens have been housed to be spread by the hens. This helps to prevent the formation of condensation water between floor and litter in case of low room temperature. Straw stimulates the investigative and feeding behavior of the hens and reduces vices. Removal and replacement of litter in heavily frequented areas of the building may become necessary during the laying period. A well designed winter garden has a positive impact on litter quality. This beneficial effect of a winter garden can be improved further by staggering the position of the popholes in the building and the winter garden.

House climate

Room temperatures around 18°C are considered optimal for laying hens in alternative systems, with a relative humidity between 50 and 75%. Lower temperatures during the winter months are no problem, provided the hens are adapted to them. But temperatures exceeding 30°C are less well tolerated. If room temperatures above 30°C cannot be avoided, sufficient air movement around the hens is essential to enable the birds to dissipate heat. Additional fans in the poultry house are highly effective in such situations.Hens with access to a winter garden or an outdoor enclosure should get accustomed to colder winter temperatures. Plumage quality needs to be considered in temperature management programs in alternative housing. Activity of the birds, stocking density and the presence of popholes are important effects on air quality and room temperature.

Draughts are harmful for the birds who may try to escape them by congregating in poorly ventilated parts of the building. Increased mortality and floor eggs may be due to poor ventilation. The ventilation system should ensure that in summer warm air is removed quickly from the birds’ surroundings and in winter the building does not become too cold. High concentrations of noxious gases should be avoided. Ammonia reduces bird comfort and is injurious to health. A well designed winter garden and the use of outdoor pens or wind protection (strip curtains) in front of the popholes prevent the ventilation system in the poultry house from breaking down if a negative pressure system is used.

In case problems occur with the ventilation system in deep litter or perchery housing, experts should be consulted.

Feeding

The high genetic potential of today’s hybrid layers for efficient egg production can only be realized with a balanced diet. The nutrient requirement of a laying hen is divided into the requirements for maintenance, growth and egg production. Recommended nutrient allowances can be formulated for any production system, for alternative management systems as well as for conventional cages. The maintenance requirement of a laying hen is approximately 60-65 % of the total energy requirement. Compared with laying hens kept in cages, the maintenance requirement in alternative systems is higher due to the increased activity of the hens. It has been calculated at +10 % for hens producing barn eggs and +15 % for hens using free range.The prerequisites for sufficiently high nutrient intake of hens are:

- a diet with a sufficiently high energy content, i.e. nutrient density

- and adequate feed intake

In case it is not economically viable to raise the nutrient density of layer diets, sufficient feed intake becomes more important for the expression of the hen’s genetic potential. The feed intake capacity of a population of laying hens can be optimized by genetic selection, for individual laying hens it is determined mainly by:

- The hen’s bodyweight

- Daily egg mass production

- Ambient temperature

- Condition of the hen’s plumage

- Energy content of the ration

- Health status

- Genetic variation within flock

Feeding at onset of lay

When pullets are moved to the laying house at 16-17 weeks of age, they are not yet fully grown and should not be fed a layer diet. Layer diets with more than 3 % calcium should not be introduced too early. Until about 19 weeks of age the hens should get a pre-lay diet, the change to a high-density layer starter should be made when about 5% production is reached. The move to the laying house exposes hens to considerable stress. The development from pullet to mature laying hen is associated with fundamental changes affecting all major physiological and hormonal processes. The phase of juvenile growth and body mass increase ends on reaching sexual maturity, followed by the start of lay. However, the hens are not yet fully grown at onset of lay, their growth continues until about 30 weeks, when the weekly weight gain falls to less than 5 g.The changes occurring during the transition phase from pullet to laying hen often lead to a reduced feed intake, which may drop to well below 100 g per hen and day. This rate of consumption does not meet the hen’s nutrient requirement at that age and, based on the energy levels of commercial layer rations in Europe, must definitely be considered too low. A suboptimal nutrient supply at the onset oflay places a strain on the birds’ metabolism as endogenous energy reserves have to be mobilized and it can contribute to the development of fatty liver syndrome.

During this phase every effort must therefore be made to increase the feed intake as quickly as possible to at least 120 g per bird and day. An effective way of boosting the nutrient intake is to offer the hens a ration with a higher nutrient density (11.6 – 11.8 MJ/kg) and correspondingly increased amino acid concentrations. An inadequate nutrient supply in early lay jeopardizes the success of the entire laying period and leads to irreversible loss of egg production.

Feeding during the laying period

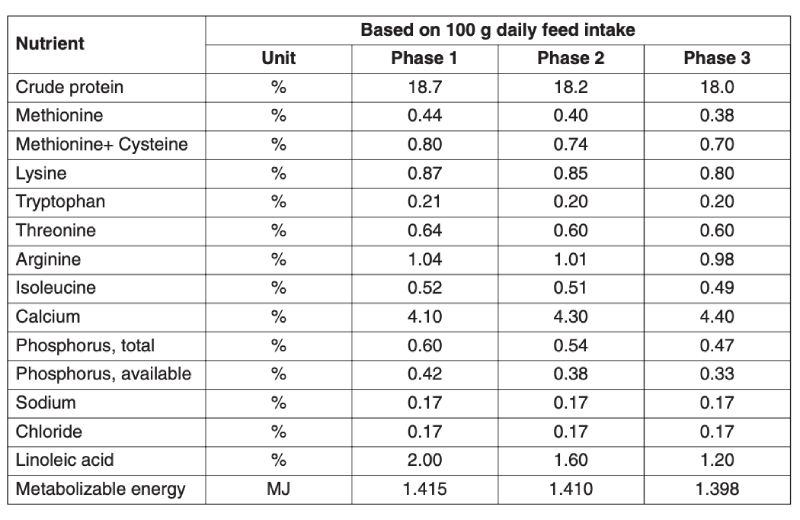

Table 1 Recommended daily nutrient allowances for brown-egg laying hens in deep litter

and free range systems*:

A universally valid conversion of these nutrient requirement data for all feeding situations, stated as nutrient content per 100 kg feed, is not possible, mainly because actual feed consumption per bird and day varies widely in real-life commercial situations. But when formulating diets for laying hens in alternative management systems it should be remembered that to achieve normal performance from hens in alternative systems requires both a diet with a higher nutrient density and the highest possible feed intake. The aim should be a daily consumption of 120 – 125 g feed per hen and day.

Phase feeding

The basis for any feeding program in alternative production systems must be the hens’ nutrient requirement. This changes continuously as the birds get older. To match the hens’ evolving nutritional needs requires diets formulated according to different criteria at each stage:- Layer starter (phase 1) with high nutrient density for a safe start to the laying period

- Balanced phase 2 diet to ensure good laying persistency with a reduced protein and amino acid content

- Phase 3 diet for optimal shell quality and corresponding egg weights

Information on recommended nutrient allowances and feeding programs for white- and brown-egg layers is available on request from Lohmann Tierzucht.

The basic principles of phase feeding can also be implemented in laying hen operations with several age groups and only one feed silo. Here, too, the hens’ changing nutrient requirements can be met by selecting appropriate feed types, although expert advice should be sought from a poultry nutritionist. But the best way of ensuring an optimal feed and nutrient supply is to have a separate feed silo for each age group. This variant is also preferable from an economic perspective. Larger holdings with several units should have two silos per unit. This facilitates cleaning of the silos and allows a quick change of diet if necessary. The alternate filling of two separate feed silos makes it easy to check the feed consumption of each flock with a view to determining the feed intake per hen. But in large operations modern, computer-controlled systems should be available for an accurate measurement of feed consumption.

Feeding and egg weight

The production of eggs of the correct weight for the market is of prime importance in alternative housing systems. Egg weight and shell quality are negatively correlated. Large eggs at the end of lay often have a poorer shell quality. Measures to control egg weight should therefore begin during the pullet rearing phase and be implemented early on. In high-production flocks a noticeable reduction in egg weight is very difficult to achieve during the laying period.It is therefore advisable to talk to the pullet producer and the feed supplier as early as possible about the diet formulations to be used.

Condition of plumage and feed intake

Maintaining the hens’ plumage in good condition throughout the production period should be a major concern of every poultry keeper. In doing so he fulfils his legal obligations under animal welfare laws, but well-maintained plumage is also essential for keeping the hens in good health. It protects against heat loss, thus restricting feed consumption. A bad plumage can easily increase daily feed intake by 10 g/day/bird and more. The increased feed and nutrient requirement of hens with damaged plumage is explained by the maintenance requirement, which accounts for 60-65 % of the total nutrient requirement and in this case is needed to maintain the birds’ body temperature. A daily feed consumption of 130 g/hen/day (or more) is therefore not unusual in special situations.Grit

Insoluble grit or fine gravel should be provided for free access feeding. Due to the specialized digestive system of birds, this can stimulate digestion and improve feed intake capacity. We recommend 3 g/hen once a month with 4 – 6 mm granulation.Water

Good water is the most important part of the diet for all animals, including poultry. To ensure health and optimum egg quality the water supplied to the hens should be of potable standard. The poultry farmer should therefore always ask himself if he would be prepared to drink the water offered to his birds himself.Feed and water intake are closely correlated. Under normal conditions the feed to water ratio is about 1:2. If hens do not drink enough, feed intake will be inadequate. Regular checks to ensure that drinkers are working properly are therefore recommended.

When ambient temperatures are high or if laying hens have health problems they consume more water. During hot weather water serves to regulate the hens’ body temperature. Cool drinking water is best for this purpose and water temperatures above 20° C should therefore be avoided. During extremely hot weather with temperatures of over 30° C the feed to water intake ratio can shift to 1:5. In such situations cooling of the drinking water is beneficial. Water meters allow regular monitoring of the hens’ water consumption. They are inexpensive and easy to install. A reduced or increased

water intake can be regarded as a first warning sign of problems in the flock or with the technology. Minimizing water wastage reduces costs and improves the house climate.

Regular cleaning of the water lines in poultry buildings is essential and special attention should be paid to checking the supply tanks. If water from wells on the farm is used regular water tests should be carried out. The assessment of water quality should be based on the standards laid down in the Drinking Water Ordinance.

Flock control

In the early days after housing a special attention to detail will pay ample dividends later on. Every morning at dawn a thorough tour of inspection is necessary. This should comprise checks for the proper functioning of:- drinkers,

- feeders,

- lighting installations and

- laying nests

The house climate should be checked and the condition of the flock and the hens’ behavior assessed.

Laying nests

Laying nests should be easily accessible to the hens, preferably located in a central location. It is recommended to keep the entrance to the nest well lit whereas the interior should be darkened. Pullets should not be allowed access to the nests too early, only just before the onset of lay. This enhances the attractiveness of the nest and improves nest acceptance. During the laying period the nests should be opened 2-3 hours before the start of the light day and closed 2-3 hours before the end of the light day. Closing the nests at night prevents soiling and broodiness. Close-out prevents the hens from roosting in the nests overnight and also makes the nest less attractive to mites. Tilting floors have proved effective for close-out. They also help keep the nest box floor clean.Floor eggs

The incidence of floor eggs can be reduced by incorporating the following experiences in the design of the laying house and the management of young flocks:- The entire building should be well lit – dark corners should be avoided.

- Draughty nests disturb the hens during egg laying.

- The entrance to the nest must be clearly visible.

- Additional lighting of the interior of the nest improves nest acceptance at the onset of lay.

- Litter depth should not exceed 2 cm at the onset of lay. Light-colored litter material is preferable to dark material.

- Feeders and drinkers should be near to the nest (2 to 3 meters).

- Drinking water in the vicinity of the nest entices the hens to this area.

- Feeders and drinkers should not create attractive areas for egg laying.

- If nest boxes are mounted on the dropping pits the perforated floors should have a gradient of about 7° towards the nest.

- Slats in front of the nests should incorporate barriers every two meters.

- Pullets should not be moved to the production facility before 17-18 weeks of age.

- The laying nests should be opened just before the onset of lay.

- Hens should not be disturbed while laying, i.e. no feeding at this time.

- Do not carry out flock inspections during the main morning laying period.

- Floor eggs should be collected from early in the morning, several times a day.

- To reduce floor laying, an extra hour of light at the start of the day is often effective.

- Electric fencing and draughts may help in problem areas.

Lighting

The best light source for laying hens is a high frequency bulb emitting light within the natural spectrum (frequency range above 2000 Hz). Fluorescent tubes or energy-saving bulbs (50-100Hz) have a ‘disco effect’ on hens and encourage feather pecking and cannibalism. Light sources should have a dimmer switch.Lighting programs

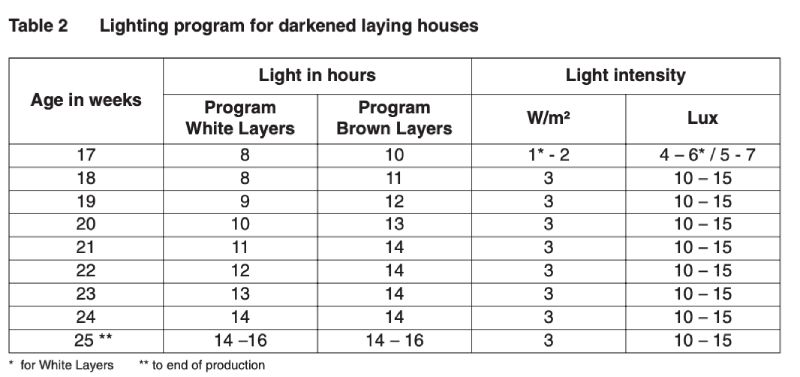

Great care must be taken to ensure that day length is not increased up to the point of stimulation for egg-laying and is not decreased during the laying period of a flock. This is easy to achieve in windowless buildings or laying houses with windows that can be blacked out, provided that foul-air and freshair shafts also have effective blackout facilities. In this case the most suitable lighting programs for the particular breeding products can be operated.Table 2 Lighting program for darkened laying houses

Special considerations for hens kept in buildings with natural daylight

In housing where the hens have access to winter gardens or an outdoor enclosure, or if windows, ventilation shafts and other openings cannot be blacked out sufficiently to shield the birds completely from the effect of natural daylight, this should be taken into consideration when designing the lighting program. If flocks are moved into these production facilities or if the hens have free access to winter gardens or outdoor areas, the lighting program must be adjusted to the natural day length.It makes a difference whether the housed pullets come from a windowless growing facility or were reared in a building whose windows were blacked-out in synchronicity with the lighting program or whether they were fully exposed to natural daylight during the growing period. In the case of hens which were unaware of the natural diurnal rhythm during rearing it is important to avoid excessive stimulation, and consequently stress, on transfer to open laying houses caused by an abrupt lengthening of the day (in spring and summer). An increase in the day length by not more than 2-3 hours is desirable.

In open housing the lighting program in the spring and summer months is determined by the lengthening of the natural day. When the natural day length begins to decrease again the day length should be maintained constant until the end of the laying period.

Crucial points to consider in the management of laying hens, the choice of light sources and the design of lighting program:

- Artificial light from fluorescent bulbs operating within a frequency range below 250 Hz is perceived as flickering by hens. Incandescent bulbs or fluorescent tubes operating at high frequencies over 2000 Hz are preferable.

- Artificial filtered light, but also unfiltered light from conventional light sources, restricts the vision of hens by limiting the light spectrum that is visible to them.

- Stimulation of hens in windowless housing follows the simple principle of shortening the light period until the desired stimulation has been achieved, followed by a lengthening of the light period. A reduction of the day length during the laying period is not allowed.

- If technically possible, open housing for laying hens should also have facilities for blacking out the windows. These could then be opened and shut in synchronicity with the lighting program.

The laying hen keeper and the pullet supplier should agree on the following in order to coordinate lighting programs during rearing and the subsequent laying period:

- If pullets are moved to open houses without a blackout facility an option is to design lighting programs synchronized with the hatch date of the flock. To avoid a “light shock” if transfer takes place during a period of very long days the step-down program during rearing should be modified in such a way that on transfer to the laying house the hens are exposed to an increase in day length of not more than two or three hours.

- Pullets should be reared in darkened housing or if windows are present, those should be opened and shut in synchronicity with the lighting program.

- Hens reared under artificial light and exposed to natural daylight later on, have to get used to it. The use of true light bulbs during pullet rearing can help.

- Pullets reared in buildings that cannot be darkened are affected by the length of the natural day, especially in the spring and summer months. Early maturing of pullets can only be prevented by adapted lighting programs, but light stimulation of such hens is difficult.

Animal health

Pullets destined for deep litter, perchery and free range systems are vaccinated in the rearing facility against viral (Marek’s Disease, IB, ND, Gumboro, ILT), bacterial (Salmonella) and parasitic diseases (coccidiosis). In alternative layer housing systems the infection pressure from fowlpox and EDS is so high that they should also be vaccinated against these diseases if there is any risk of infection. Combined vaccinations against IB, ND, EDS and sometimes also against ART are widely applied.Booster vaccinations against IB are advisable at 5-10-week intervals. A high infection pressure of Salmonella requires, in addition to the vaccinations given during rearing, an additional booster vaccination. Bacterial infections such as E. coli, erysipelas and Pasteurella multocida are common in alternative production systems. Outbreaks depend on the type of infectious agent, the infection pressure and the condition of the flock. Immune protection can also be achieved by combined vaccinations. Effective treatment of bacterial infections in laying hens is hardly possible. Preventative vaccination with flock-specific vaccines is therefore advisable. This initial outlay can help prevent high losses and a premature end to production. The bacteria causing erysipelas and Pasteurella infections are usually found in rodent pests in the vicinity of affected hens. Effective control of mice and rats is an important tool for prevention.

If high mortality rates or any other signs of disease are observed in the flock, a veterinarian should be consulted immediately.

Parasites

Roundworms and threadworms occur in hens and are transmitted via the droppings. If necessary the flock may have to be wormed.Red poultry mites are a major problem in alternative production systems. They damage health and reduce the productivity of flocks. Heavy infestation can also cause high mortalities (by transmitting diseases). Infestation causes distress in the flock (feather pecking, cannibalism, depressed production). Continuous monitoring of the flock is therefore advisable.

Common hiding places of mites are:

- in corners of nest boxes

- under the next box covers

- on the feet of feeding chains, trough connectors

- on dropping box trays

- in corners of walls and

- inside the perches (hollow tubes)

Mites should be controlled with insecticides or other suitable chemicals. These should be applied in the evening as mites are active during the night. It is important that the treatment reaches all hiding places of the mites. More important than the amount of chemicals applied is their thorough and even distribution. The mite and beetle treatment should begin as soon as the flock has been depopulated, while the laying house is still warm. Otherwise the pests crawl away and hide in inaccessible areas of the laying house.

Vices

Watch closely for any signs of abnormal behavior. A sudden occurrence of it without changes in the lighting regime can have a variety of reasons. If these vices occur check the following factors:- Nutritional and health status – bodyweight, uniformity, signs of disease

- Stocking density – overcrowding or insufficient feeders and drinkers cause distress

- House climate – temperature, humidity, air exchange rate or pollution by dust and/or noxious gases

- Light intensity / light source – excessive light intensity and flickering light (fluorescent tubes or energy-saving bulbs, < 200 Hz )

- Ecto- and endoparasites – infested birds are distressed and develop diarrhoea

- Feed consistency – finely ground meal-type feed or pelleted feed encourage vices

- Protein/amino acid content of the diet – deficiencies cause problems

- Supply of calcium and sodium – deficiency makes birds irritable

Outdoor enclosure

Access to outdoor enclosures should be managed in accordance with external weather conditions. For the first three weeks after transfer the hens should remain indoors. Then the popholes should be opened. If a winter garden is available this should initially be opened for just one week, before eventually opening the exit popholes 4-5 weeks after housing. Popholes should only be opened after eggs have been laid. Young flocks going outside for the first time need to be trained in the use of the outdoor enclosure. Food and water are only available indoors.Range/Pasture

Hens readily accept the range if the pasture area is broken up by a few trees or shrubs which provide protection from predators. The area closest to the laying house is heavily used by the flock and the grass becomes worn. Depending on the condition of this part of the range, ground care and disinfection measures should be carried out. Pasture rotation has proved effective in practice. Young pullets visiting pastures with good vegetation for the first time tend to ingest numerous plants, stones, etc. This can often greatly reduce their feed intake capacity. Failure to consume sufficient food, especially during the phase of peak egg production, jeopardizes the hens’ nutrient supply. In practice this often leads to weight loss, reduced production and increased susceptibility to disease. Young flocks should therefore be introduced gradually to using the outdoor areas.Zusammenfassung

Managementempfehlungen für die Haltung von Legehennen in Boden-, Volieren-, und FreilandhaltungenDas Management von Legehennen in Boden-, Volieren- und Freilandhaltung erfordert gegenüber der herkömmlichen Käfighaltung wesentlich mehr Sachkenntnis und Zeit, die zur Betreuung der Tiere investiert werden sollte. Besondere Beachtung sollten folgende Gesichtspunkte finden:

• Junghennen, die in Boden- und Volierenhaltungen eingestallt werden, sollten auch in solchen Haltungen aufgezogen worden sein. Je ähnlicher der Aufzuchtstall dem späteren Produktionsstall ist, desto besser werden sich die Tiere im neuen Stall eingewöhnen.

• Die Tiere müssen bezüglich des Körpergewichts und der Uniformität dem Standard des Züchters entsprechen und sie sollten über ein gutes Futteraufnahmevermögen verfügen.

• Der Schnabel der Junghennen, die in alternative Haltungsformen eingestallt werden, sollte behandelt worden sein, um Federpicken und unnötigen Tierverlusten vorzubeugen.

• Nach der Umstallung in den Legestall im Alter von 17-18 Wochen ist darauf zu achten, dass die Tiere unverzüglich Futter und Wasser aufnehmen und weiter wachsen. Ein Körpergewichtsverlust oder ein Stagnieren des Wachstums der Hennen sind unter allen Umständen zu vermeiden.

• Ein gutes und im gesamten Stallbereich einheitliches Klima ist in Alternativhaltungen besonders wichtig. Staub und Zugluft sind zu vermeiden. Temperaturen von 18° C und eine relative Luftfeuchte im Bereich von 50-75 % sind optimal.

• Bei der Fütterung der Tiere ist zu beachten, dass diese einen um 10-15 % höheren Erhaltungsbedarf haben als in der Käfighaltung.

• Bei Einsatz eines hochwertigen Legestarter Futters können Defizite in der Futter- bzw. Nährstoffaufnahme zu Beginn der Legeperiode ausgeglichen werden.

• Phasenfütterung ist zur Steuerung des Eigewichtes und der Futterkostenoptimierung auch für Alternativhaltungen zu empfehlen.

• Gut konstruierte, im Stall räumlich richtig angeordnete Legenester, ein gutes Nestmanagement und angepasste Fütterungszeiten helfen, den Anteil verlegter Eier zu minimieren. Die Hennen müssen frühzeitig lernen, zur Eiablage das Nest aufzusuchen. Hennenhalter müssen zu Legebeginn dem Verlegen von Eiern durch geeignete Maßnahmen entgegenwirken.

• Herden in Offenställen brauchen spezielle, auf das Schlupfdatum der Herde und die geographische Lage des Stalles angepasste, Beleuchtungsprogramme.

• Infektionsdruck und Belastung der Tiere durch bakterielle Erkrankungen sind in Alternativhaltungen wesentlich höher als in Käfighaltungen. Dies ist bei der Gestaltung von Impfprogrammen und der Prävention von Erkrankungen zu berücksichtigen.

• Hennen müssen an Freilandhaltungen gewöhnt werden. Bei der Nutzung von Ausläufen ist insbesondere darauf zu achten, dass die Tiere im Stall immer genügend Futter aufnehmen.

• Freilandausläufe sind zu pflegen, um einer Kontamination des Bodens mit Schadstoffen und Parasiten vorzubeugen.

Suscríbete a nuestro Newsletter

Y entérese de todas las novedades del sector.