Dr. Vera Sommerfeld studied Agricultural Biology at the University of Hohenheim in Stuttgart, Germany. Supervised by Prof. Dr. Markus Rodehutscord, she completed her PhD at the Institute of Animal Science at the University of Hohenheim in 2017. She now is a research associate mainly focused on poultry nutrition.

v.sommerfeld@uni-hohenheim.de

ABSTRACT

Laying hens are typically managed with phase-feeding systems that account for their changing nutritional requirements over the production cycle. Yet, these requirements not only evolve over the period of weeks and months, but also fluctuate within a single day, following the circadian rhythm of egg formation.

Under free-choice conditions, hens have shown to adjust their intake accordingly: They preferentially consumed protein- and energy-rich feed around oviposition and shortly thereafter, while exhibiting a marked appetite for calcium in the afternoon. Based on this knowledge, the concept of split feeding has emerged.

This work outlines the principles of split feeding and highlights recent research findings on its application in laying hens. Due to the heterogeneity of study designs, firm conclusions are not possible yet.

Nonetheless, recent studies converge on a key point: aligning feed supply with the circadian requirements of laying hens may sustain–or even improve–production performance, while at the same time lowering feed costs and reducing environmental impact. Current evidence, however, remains inconsistent, underscoring the need for long-term, large-scale trials to confirm or challenge these promising results.

INTRODUCTION

Laying hens are commonly managed with a phase-feeding system, consisting of starter, developer, pre-layer and layer diets. The layer feed itself is usually divided into three or more phases, aiming to match the hen’s changing nutritional requirements throughout the production cycle as closely as possible. In practice, however, such systems always represent a compromise between optimal nutrient supply and practical feasibility. Importantly, the nutrient requirements of laying hens not only change over the course of the production period, but also fluctuate on a much finer level, on a daily scale.

As early as the beginning of the 20th century, observations revealed that hens adjust their feed intake according to their laying activity. Kempster (1917) reported that hens consumed more oyster shell on days when they laid an egg compared to non-laying days, highlighting the importance of ensuring adequate calcium availability to meet the hen’s immediate needs. Subsequent studies investigated the role of individual “eating instincts” of chickens in achieving balanced nutrition and the resulting physiological outcomes (Dove 1935). Further studies focused on selective intake of specific feed components (Emmans 1977, Holcombe et al. 1976, Mongin and Sauveur 1974) and demonstrated that feed intake patterns follow the hen’s circadian rhythm and oviposition cycle (Hughes 1972, Morris and Taylor 1967, Wood-Gush and Horney 1970).

These early findings laid the foundation for the concept of split feeding–an approach designed to provide laying hens with certain nutrients at the specific time of day when required for egg and eggshell formation. This tailored approach aims for an efficient use of nutrients and to support the needs of modern high-producing hens. In this overview, the principles of split feeding and the latest research results on its application in laying hens will be presented.

PHYSIOLOGICAL BASIS OF NUTRIENT REQUIREMENTS IN LAYERS

Nutrient requirements for laying hens are usually derived using factorial approaches. These consider the requirement for maintenance, deposition in the egg, and, in the case of growing birds, tissue accretion. To account for incomplete absorption and utilization, a fixed efficiency factor is applied, typically established through experimental studies. Summing up these components–depending in case of GfE (1999) on body weight (and growth) as well as egg mass–yields a daily recommendation for the respective nutrient. Such recommendations are rationale in principle on a quantitative level. However, certain peculiarities of the laying hen introduce a level of complexity that goes beyond these seemingly straightforward values.

A contemporary hybrid laying hen produces on average almost one egg per day. Each cycle begins with the release of the most mature follicle, after which the yolk enters the infundibulum, the first segment of the oviduct. In the magnum, albumen is secreted over 2-3 hours, followed by the deposition of the shell membranes in the isthmus over about 1.5 hours–both consisting largely of protein. Calcification and pigmentation of the egg then occur in the uterus, or shell gland, for roughly 20 hours, before the egg is finalized with the formation of the cuticle. Oviposition takes place after 24-26 hours, and the next follicle immediately starts its maturation process (for a detailed overview see Molnár et al. (2018a)).

The circadian pattern has two key implications. First, hens may require more protein in the early stages of egg formation than later in the cycle. Second, their demand for calcium peaks during the period of shell calcification. The challenge arises because calcification usually occurs at night, when hens do not eat. Thus, calcium needed for shell deposition must be mobilized from medullary bone reserves.

Unlike structural and trabecular bone, which develop during early life and consist of highly organized hydroxyapatite crystals, medullary bone forms only at the onset of sexual maturity under the influence of estrogen. It is composed of loosely organized crystals in the long bones, enabling rapid deposition and resorption (Sinclair-Black et al. 2023). These reserves are depleted during shell formation and rebuilt after oviposition.

Moreover, nutrient digestibility can vary throughout the day, depending on the hen’s actual physiological needs (Hurwitz and Bar, 1965, Hurwitz et al. 1973, Sinclair-Black 2019). Taken together, these dynamics illustrate that the hen’s nutrient requirements fluctuate with the time of day, making a static, uniform nutrient concentration across 24 hours suboptimal–not only in terms of efficiency but also for animal welfare.

In studies where laying hens were provided with a separate calcium source, voluntary intake was generally low and showed only minor fluctuations on days without egg laying.

On laying days, however, calcium consumption increased between 2 PM and 5 PM before gradually declining again (Hughes 1972).

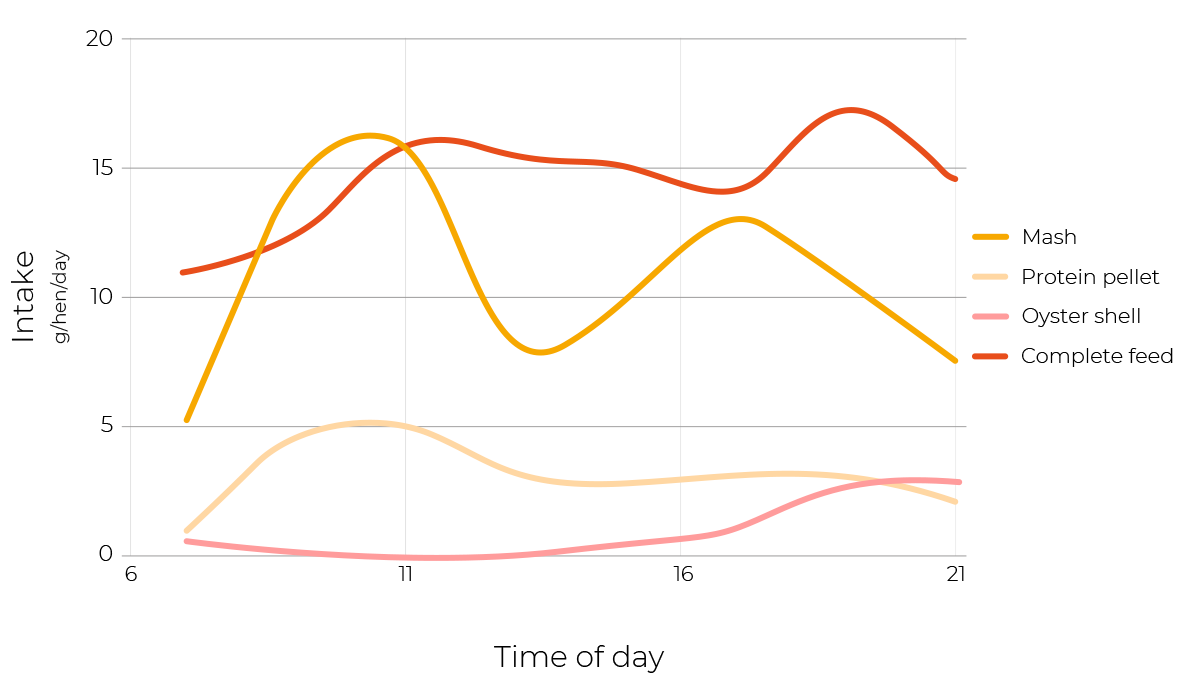

When hens were offered separate feed mixtures under free-choice conditions, most of them selected protein- and energy-rich feed around the time of oviposition and shortly thereafter, while exhibiting a distinct calcium appetite in the afternoon hours (Figure 1.).

Voluntary intake of a complete diet or free choice of a high-energy mash, protein pellet, and oyster shell flakes (aka “cafeteria”) (after Chah and Moran 1985).

This “cafeteria” feeding approach resulted in lower overall feed consumption but higher utilization of energy, protein, and calcium, as well as an increased eggshell strength (Chah and Moran 1985). Summarising research on choice feeding, Henuk and Dingle (2002) concluded that poultry are capable of self-selecting a diet that meets their specific circadian requirements. While the rhythm of egg production and oviposition influences nutrient requirements and intake, it has also been shown that a timely adjustment of nutrient supply, as implemented in choice or split feeding, can alter the oviposition rhythm without affecting egg production per se (Chah and Moran 1985; Jordan et al. 2010). Henuk and Dingle (2002) also emphasized potential economic benefits, such as energy savings from avoiding grinding, mixing, and pelleting of complete diets, along with reduced overall feed or nutrient intake.

As summarised by Molnár et al. (2018a), choice-feeding showed no or even decreasing effects on feed conversion ratio, feed intake, energy intake, and protein intake compared to conventional systems. Egg production, egg weight, and egg mass were unaffected or even increased. For a comprehensive overview of choice feeding in laying hens, the reader is referred to the reviews by Henuk and Dingle (2002) and Molnár et al. (2018a).

In addition to the conventional system of offering a complete feed for ad libitum consumption in mash or pellet form, alternative feeding concepts have emerged. These approaches are based on the circadian rhythm of laying hens and their needs for certain nutrients according to the physiological demands of egg formation: protein and energy in the morning, calcium in the evening.

Several strategies can be applied, each with specific advantages and limitations, e.g.:

1. Cafeteria feeding: Hens are offered separate diets rich in protein or energy, along with an additional calcium source, from which they can freely select according to their needs.

2. Split feeding: Two different mixed feeds are provided, one in the morning and one in the evening, each adjusted in nutrient concentration to match the hen’s requirements at that time of day.

3. Variation in calcium particle size: The distribution of fine and coarse calcium carbonate is adjusted between morning and evening diets, sometimes within a split feeding concept.

The latter is based on different physical properties of calcium carbonate sources. Most calcium carbonate sources with a particle size that is defined as “fine” (usually < 1000 µm diameter), dissolve rapidly and are quickly available, while “coarse” calcium carbonate sources (usually > 1000 µm diameter) remain longer in the digestive tract and release calcium more gradually. This slow release is particularly beneficial during the night, when hens do not consume feed and must rely on calcium reserves for eggshell calcification.

Protecting bone integrity is particularly important in the context of prolonged laying cycles, as older hens frequently produce large, thin-shelled eggs while suffering from weakened skeletal structure. Once medullary reserves are exhausted, calcium mobilization from structural bone may lead to osteoporosis (Gloux et al. 2020, Sinclair-Black et al. 2023). Providing coarse calcium carbonate particles before the night can therefore reduce the mobilization of medullary bone.

Supporting this concept, a meta-analysis by Hervo et al. (2022) demonstrated that increasing calcium carbonate particle size from 0.15 to 1.5 mm increased tibia breaking strength in laying hens.

Moreover, a more precise and need-based nutrient supply not only supports eggshell quality and skeletal health but may also reduce total nutrient intake and the risk of undesirable interactions, such as those involving phytate.

CURRENT RESEARCH FINDINGS

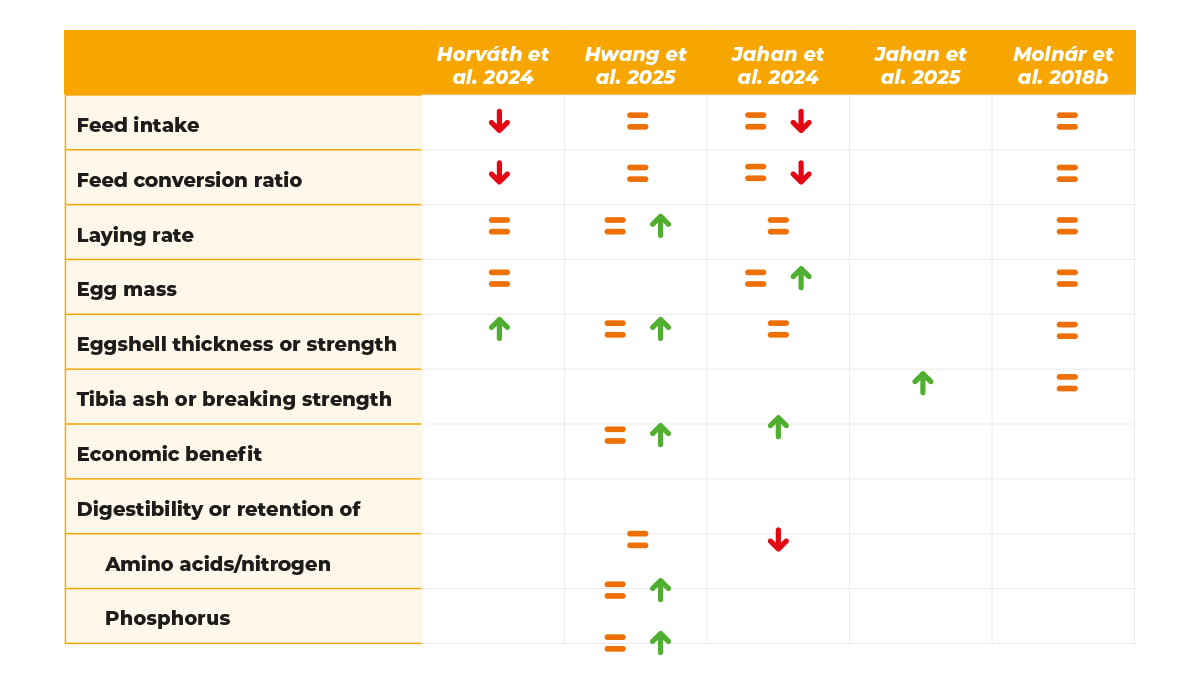

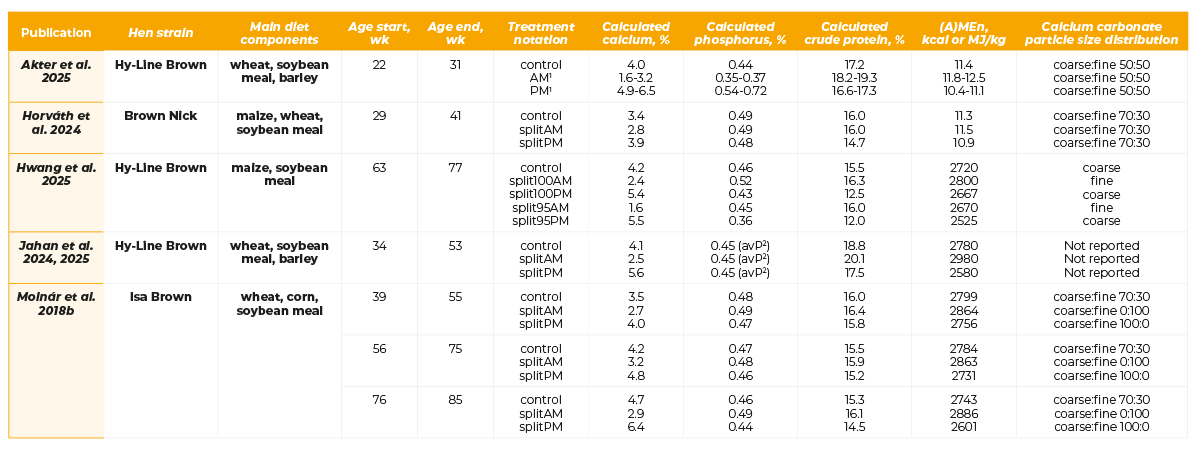

Although the body of literature on split feeding in laying hens has grown in recent years, it remains relatively limited. Reviewing earlier studies on split feeding with varying levels of protein, energy, calcium, and different calcium particle sizes (Faruk et al. 2010a,b, Keshavarz 1998a,b, Lee and Ohh 2002, de los Mozos et al. 2012, Traineau et al. 2013), Molnár et al. (2018a) and Horváth et al. (2024) concluded that split feeding did not impair performance and often (though not consistently) improved feed efficiency and increased egg shell quality. More recent findings provide further insights and are summarized in Table 1. with details regarding experimental setup displayed in Table 2..

Increases (↑), decreases (↓) or no changes (=) in various traits in laying hens by applying a split-feeding programme compared to a control diet.

Two studies reported improvements by split feeding in feed conversion ratio of 0.1 kg/kg (week 29-41; Horváth et al. 2024) and 0.21 or 0.26 kg/kg (week 34-53 and week 44-53; Jahan et al. 2024). Egg mass increased by 1.5 g/hen/day between weeks 34-43 (Jahan et al. 2024). The effect was not significant for the period from 44-53 weeks and the total experimental duration of 20 weeks. Overall, split feeding generally exerted only minor or no effects on the laying hen performance (Hwang et al. 2025, Molnár et al. 2018b).

In terms of eggshell quality, split feeding increased eggshell thickness by 0.03 mm (Horváth et al. 2024). While no difference in eggshell strength was observed in some cases (Horváth et al. 2024), other studies reported increases of 0.11 kg/cm2 in week 8 or by 0.28 kg/cm2 in week 12 of experimental feeding (Hwang et al. 2025).

Relative shell weight also tended to be higher under split feeding (Molnár et al. 2018b), and the proportion of downgraded eggs was reduced by up to 0.6 percentage points (Hwang et al. 2025).

Nutrient utilization also benefited: split feeding increased prececal digestibility of certain amino acids (Horváth et al. 2024), enhanced phosphorus and calcium digestibility (Hwang et al. 2025), and in some cases increased tibia ash content and breaking strength (Jahan et al. 2025).

At the same time, it reduced protein and nitrogen intake, lowered nitrogen excretion (Horváth et al. 2024), and reduced gaseous emissions (Hwang et al. 2025).

Beyond physiological outcomes, behavioral benefits were also observed. Jahan et al. (2025) reported reduced feather pecking, greater outdoor range use, and a prolonged time exploring novel objects. Economically, higher eggshell quality translated into lower feed costs per saleable egg (Hwang et al. 2025, Jahan et al. 2024).

Using a Box-Behnken response surface methodology, Akter et al. (2025) identified an optimal split feeding regimen, at least for hens of 20 to 31 weeks of age: a morning diet with 21% crude protein, 3.3% calcium and 12 MJ metabolizable energy/kg feed, and an evening diet with 17% crude protein, 4.9% calcium and 11.1 MJ metabolizable energy/kg feed, achieving the best balance of feed efficiency and cost.

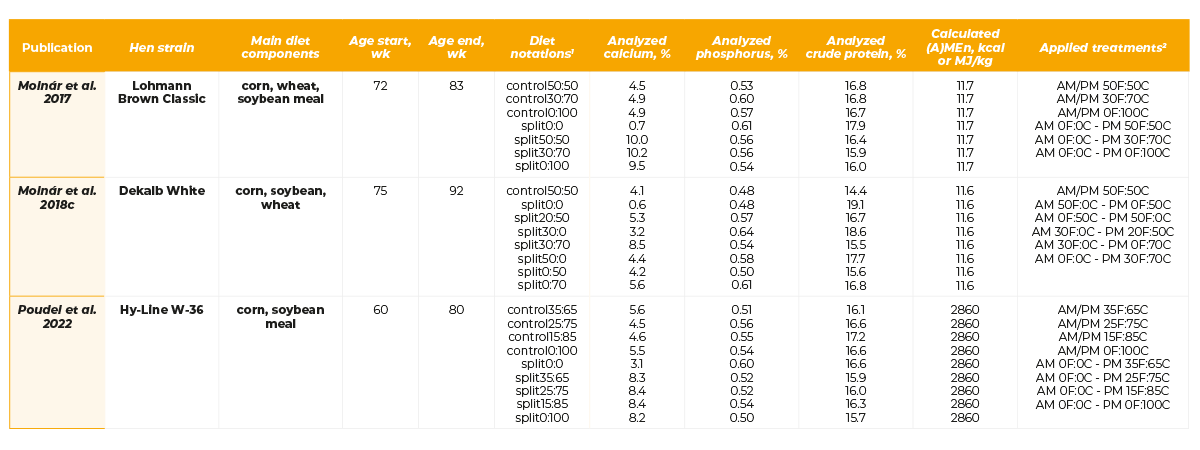

CONSIDERING CALCIUM CARBONATE PARTICLE SIZE DISTRIBUTION

The timing of provision of different calcium carbonate particle sizes can markedly influence performance traits. Details of experiments investigating this subject are summarized in Table 3. When hens received coarse calcium carbonate in the morning and fine in the evening, body weight, feed intake, egg weight and laying performance were significantly reduced after 82 weeks.

In contrast, offering fine calcium carbonate particles in the morning and coarse in the evening increased feed intake and laying performance, despite both groups receiving the same total daily calcium amount (Molnár et al. 2018c).

In the same study, adjusting calcium concentrations–higher in the evening and lower in the morning–did not increase shell quality. Similar effects were observed by Poudel et al. (2022), who reported increased feed intake when fine calcium carbonate was omitted. Their split feeding program also enhanced eggshell breaking strength in older hens.

However, an excessively high proportion of coarse particles impaired tibia breaking strength compared with ratios of 35:65 or 25:75 fine:coarse.

Molnár et al. (2017) found that production traits increased when coarse calcium carbonate accounted for at least 50% of the dietary calcium, whether under standard or split feeding conditions. Yet, proportions higher than 30:70 (fine:coarse) were not advantageous in split feeding. While the split feeding program increased tibia ash content relative to standard feeding, it did not affect other egg quality traits.

A major challenge in interpreting these findings lies in the considerable variation in calcium sources, particle sizes, and solubilities. Gilani et al. (2022) demonstrated that materials classified as “fine” ranged from 38 to 992 µm, while “coarse” samples varied from 302 to 3068 µm.

Although solubility generally decreases with increasing particle size, exceptions exist (Plumstead et al. 2020), and the true solubility can only be confirmed by direct testing of the respective source. Such variability likely contributes to the divergent outcomes reported across studies.

PRACTICAL IMPLEMENTATION IN POULTRY SYSTEMS – CHALLENGES AND LIMITATIONS

A split feeding system can be implemented relatively easily when poultry houses are already equipped with feeder lines and two silos (Akter et al. 2025). According to Jahan et al. (2024), additional investments may include a system to weigh the feed and automate the change of feed. However, the authors emphasize that continuous advances in equipment and IT solutions will further facilitate the practical application of such systems.

The critical point in practice is to prevent mixing or misallocating the two diets. Offering a low-calcium diet in the evening, for example, can severely compromise eggshell quality and skeletal health. Therefore, feeders must be monitored regularly, and adjustments in feed intake–caused by temperature fluctuations, stress, activity, or other factors–should be made promptly (Molnár et al. 2018b).

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Most current experiments are limited to individual or small-group housing over relatively short periods. Future field studies are therefore essential and should account for additional factors such as bird genotype, activity level, group size, and behavior, environmental conditions, lighting programs, heat stress, gut microbiota, quality of feed ingredients and the optimal nutrient concentrations and particle sizes for the respective diets (Hwang et al. 2025, Molnár et al. 2018a,b, Moss et al. 2023, Akter et al. 2025, Jahan et al. 2024).

The existing evidence indicates a particular tendency, and long-term, large-scale trials are required to substantiate–or challenge–these findings (Molnár et al. 2018b). Given the heterogeneity of experimental designs (Table 2 and Table 3), no definitive conclusions can yet be drawn.

Setup of the experiments investigating effects of split-feeding on traits in laying hens.

1 13 treatments with three levels of crude protein (19.6%/18.4%, 20.3%/17.7%, 21%/17%), calcium (3.3%/4.9%, 2.5%/5.7%, 1.6%/6.6%), and apparent metabolizable energy (AME) (12 MJ/kg/11.2 MJ/kg, 12.4 MJ/kg/10.8 MJ/kg, 12.8 MJ/kg/10.4 MJ/kg) for AM/PM diets respectively

2 available phosphorus

Setup of the experiments investigating effects of feeding different calcium carbonate particle ratios in a split-feeding system on traits in laying hens.

1 diets were either fed in the morning (AM) and evening (PM), or different diets were used for AM and PM feeding

2 treatments show the respective combinations of diets for AM and PM feeding

C = coarse, F = fine

References

Akter, N., Dao, T.H., Crowley, T.M., Moss, A.F. (2025) Optimization of split feeding strategy for laying hens through a response surface model. Animals 15:750.Chah, C.C., Moran Jr., E.T. (1985) Egg characteristics of high performance hens at the end of lay when given cafeteria access to energy, protein, and calcium. Poultry Science 64:1696-1712.

Dove, W. F. (1935) A study of individuality in the nutritive instincts and of the causes and effects of variations in the selection of food. The American Naturalist 69:469-544.

Gesellschaft für Ernährungsphysiologie (GFE) (1999) Empfehlungen zur Energie- und Nährstoffversorgung der Legehennen und Masthühner (Broiler). DLG-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Gilani, S., Mereu, A., Li, W., Plumstead, P.W., Angel, R., Wilks, G., Dersjant-Li, Y. (2022) Global survey of limestone used in poultry diets: calcium content, particle size and solubility. Journal of Applied Animal Nutrition 10:19-30.

Gloux, A., Le Roy, N., Même, N., Piketty, M.L., Prié, D., Benzoni, G., Gautron, J., Nys, Y., Narcy, A., Duclos, M.J. (2020) Increased expression of fibroblast growth factor 23 is the signature of a deteriorated Ca/P balance in ageing laying hens. Scientific Reports 10:211124.

Emmans, G.C. (1977) The nutrient intake of laying hens given a choice of diets, in relation to their production requirements. British Poultry Science 18:227-236.

Faruk, M.U., Bouvarel, I., Même, N., Rideau, N., Roffidal, L., Tukur, H.M., Bastianelli, D., Nys, Y., Lescoat, P. (2010a) Sequential feeding using whole wheat and a separate protein-mineral concentrate improved feed efficiency in laying hens. Poultry Science 89:785-796.

Faruk, M.U., Bouvarel, I., Même, N., Roffidal, L., Tukur, H.M., Nys, Y., Lescoat, P. (2010b) Adaptation of wheat and protein-mineral concentrate intakes by individual hens fed ad libitum in sequential or in loose-mix systems. British Poultry Science 51:811-820.

Henuk, Y.L., Dingle, J.G. (2002) Practical and economic advantages of choice feeding systems for laying poultry. World’s Poultry Science Journal 58:199-208.

Hervo, F., Narcy, A., Nys, Y., Létourneau-Montminy, M.-P. (2022) Effect of limestone particle size on performance, eggshell quality, bone strength, and in vitro/in vivo solubility in laying hens: a meta-analysis approach. Poultry Science 101:101686.

Holcombe, D.J., Roland, D.A., Harms, R.H. (1976) The ability of hens to regulate protein intake when offered a choice of diets containing different levels of protein. Poultry Science 55:1731-1737.

Horváth, B., Strifler, P., Such, N., Wágner, L., Dublecz, K., Baranyay, H., Bustyaházai, L., Pál, L. (2024) Developing a more sustainable protein and amino acid supply of laying hens in a split feeding system. Animals 14:3006.

Hughes, B.O. (1972) A circadian rhythm of calcium intake in the domestic fowl. British Poultry Science 13:485-493.

Hurwitz, S., Bar, A. (1965) Absorption of calcium and phosphorus along the gastrointestinal tract of the laying fowl as influenced by dietary calcium and egg shell formation. The Journal of Nutrition 86:433-438.

Hurwitz, S., Bar, A., Cohen, I. (1973) Regulation of calcium absorption by fowl intestine. American Journal of Physiology 225:150-154.

Hwang, H.S., Lim, C., Eom, J., Cho, S. Kim, I.H. (2025) Split-feeding as a sustainable feeding strategy for improving egg production and quality, nutrient digestibility, and environmental impact in laying hens. Poultry Science 104:105100.

Jahan, A.A., Dao, T.H., Morgan, N.K., Crowley, T.M., Moss, A.F. (2024) Effects of AM/PM diets on laying performance, egg quality, and nutrient utilisation in free-range laying hens. Applied Sciences 14:2163.

Jahan, A.A., Dao, H.T., Rana, Md.S., Taylor, P.S., Crowley, T.M., Moss, A.F. (2025) Effects of AM/PM feeding on behaviour, range use and welfare indicators of free-range laying hens. Animal Production Science 65:AN24258.

Jordan, D., Faruk, M.U., Lescoat, P., Ali, M.N., Štuhec, I., Bessei, W., Leterrier, C. (2010) The influence of sequential feeding behaviour, feed intake and feather condition in laying hens. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 127:115-124.

Kempster, H.L. (1917) Food selection by laying hens. Journal of the American Association of Instructors and Investigators of Poultry Husbandry 3:26-29.

Keshavarz, K. (1998a) Investigation on the possibility of reducing protein, phosphorus, and calcium requirements of laying hens by manipulation of time of access to these nutrients. Poultry Science 77:1320-1332.

Keshavarz, K. (1998b) Further investigations on the effect of dietary manipulation of protein, phosphorus, and calcium for reducing their daily requirement for laying hens. Poultry Science 77: 1333-1346.

Lee, K.H., Ohh, Y.S. (2002) Effects of nutrient levels and feeding regimen of a.m. and p.m. diets on laying hen performances and feed cost. Korean Journal of Poultry Science 29:195-204.

Molnár, A., Maertens, L., Ampe, B., Buyse, J., Zoons, J., Delezie, E. (2017) Supplementation of fine and coarse limestone in different ratios in a split feeding system: Effects on performance, egg quality, and bone strength in old laying hens. Poultry Science 96:1659-1671.

Molnár, A., Hamelin, C., Delezie, E., Nys Y. (2018a) Sequential and choice feeding in laying hens: adapting nutrient supply to requirements during the egg formation cycle. World’s Poultry Science Journal 74: 199–210.

Molnár, A., Kempen, I., Sleeckx, N., Zoons, J., Maertens, L., Ampe, B., Buyse, J., Delezie, E. (2018b) Effects of split feeding on performance, egg quality, and bone strength in brown laying hens in aviary system. Journal of Applied Poultry Research 27:401-415.

Molnár, A., Maertens, L., Ampe, B., Buyse, J., Zoons, J., Delezie, E. (2018c) Effect of different split-feeding treatments on performance, egg quality, and bone quality of individually housed aged laying hens. Poultry Science 97:88-101.

Mongin, P., Sauveur, B. (1974) Voluntary food and calcium intake by the laying hen. British Poultry Science 15:349-360.

Morris, B.A., Taylor, T.G. (1967) The daily food consumption of laying hens in relation to egg formation. British Poultry Science 8:251-257.

Moss, A.F., Dao, T.H., Crowley, T.M., Wilkinson, S.J. (2023) Interactions of diet and circadian rhythm to achieve precision nutrition of poultry. Animal Production Science 63:1926-1932.

Mozos de los, J., Gutierrez del Alamo, A., Van Gerwe, T., Sacranie, A. (2012) Effect of reduced energy and protein levels of the afternoon diets on performance of laying hens using the oviposition determined feeding system. Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Australian Poultry Science Symposium, Sydney, pp. 283-286.

Plumstead, P.W., Sinclair-Black, M. and Angel, C.R. (2020) The benefits of measuring calcium digestibility from raw materials in broilers, meat breeders, and layers. Proceedings of the Australian Poultry Science Symposium 31:24-31.

Poudel, I., McDaniel, C.D., Schilling, M.W., Pflugrath, D., Adhikari, P.A. (2022) Role of conventional and split feeding of various limestone particle size ratios on the performance and egg quality of Hy-Line® W-36 hens in the late production phase. Animal Feed Science and Technology 283:115153.

Sinclair-Black, M. (2019) Assessment of in vivo calcium and phosphorus digestibility in commercial laying hens fed limestone with different particle sizes. Master’s Thesis. University of Pretoria.

Sinclair-Black, M., Garcia-Mejia, R.A., Blair, L.R., Angel, R., Arbe, X., Cavero, D., Ellestad, L.E. (2023) Circadian regulation of calcium and phosphorus homeostasis during the oviposition cycle in laying hens. Poultry Science 103:103209.

Traineau, M., Bouvarel, I., Mulsant, C., Roffidal, L., Launay, C., Lescoat, P. (2013) Effects on performance of ground wheat with or without insoluble fiber or whole wheat in sequential feeding for laying hens. Poultry Science 92:2475-2486.

Wood-Gush, D.G.M., Horney, A.R. (1970) The effect of egg formation and laying on the food and water intake of Brown Leghorn hens. British Poultry Science 11:459-466.

Suscríbete a nuestro Newsletter

Y entérese de todas las novedades del sector.