Summary

Genetic and non-genetic factors influence egg weight of commercial layers and should be controlled

by farm management before production of a flock starts: the genetic profile of a strain cross with

regard to egg weight and correlated traits, the light stimulation during rearing and the bodyweight or

frame size development of the pullets. Once a flock is in production, the nutrient intake, especially

the early feed intake, has a major effect on the egg weight curve. Modern layer nutrition is focused on

meeting the demands of the birds at all times by adjusting the supply of nutrients according to daily

egg mass production and daily feed intake. Precision supply of nutrients influencing egg size is a tool

to adjust the egg weight on mid or short term basis. The option to increase egg size by molting,

keeping hens for two or more cycles, is losing support due to economic and welfare reasons.

Introduction

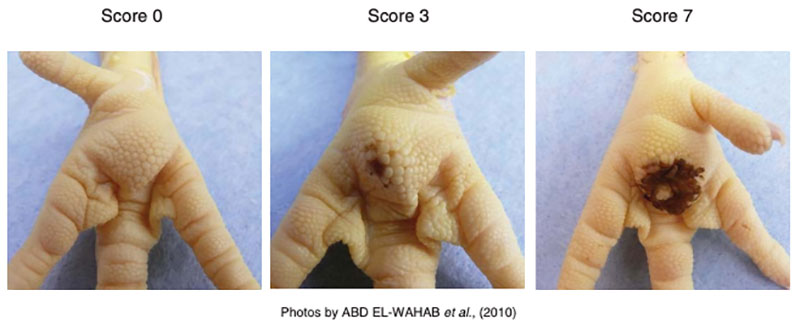

Actions concerning animal health in the turkey production are coming more and more to the fore. Foot pad dermatitis (FPD) is a common challenge to poultry production. FPD, also known as plantar pododermatitis, is basically a type of contact dermatitis affecting the plantar region of the feet, with lesions that begin as small scaly brown scabs on the surface of the metatarsal and digital pads, becoming cracked and eroded and progressively larger over the first few weeks of life along with acute inflammation, swelling, hyperplasia and necrosis of the epidermis with deep ulcers occurring in severe cases (GREENE et al., 1985; BREUER et al., 2006). The ulcers are often covered by crusts formed by exudates, faecal material and litter. Although there are various estimates of its prevalence, it is difficult to compare findings because the scoring systems used in different experiments are not the same. In a survey carried out by EKSTRAND and ALGERS (1997) 98 % of Swedish turkey poults had signs of FPD. BERG (1998) estimated the prevalence of FPD in Swedish turkeys to be 20 % for severe lesions (ulcers) and 78 % for mild lesions (discolouration, erosion). FPD can achieve a prevalence of 91-100 % in fattening turkeys (HAFEZ et al., 2004). Also, GROSSE LIESNER (2007) found that about 97 % of turkeys at slaughtering showed FPD lesions, but without any negative adverse effects on final body weight.FPD is an important aspect of bird welfare, as in severe cases, the foot pad lesions may cause pain which together with a deteriorated state of health constitutes a welfare issue. The growing demand for least-cost, wholesome and convenient food products has been the driver for the expansion and diversification of the poultry industry. The rate of FPD incidence per farm is gaining recognition as a well-being indicator (BRADSHAW et al., 2002; MARTRENCHAR et al., 2002). Moreover, lesions on the feet may be a gateway for bacteria which might affect carcass quality (MAYNE et al., 2006). The aetiology of FPD is a complex interaction of different factors. Some of these are related to dietary factors such as proportion of soybean meal and amounts of oligosaccharides, potassium and salt in feed that force wet litter conditions (JENSEN et al., 1970; SMITH et al., 2000; EICHNER et al., 2007; BILGILI et al., 2009; YOUSSEF, 2011). Other factors are related to management and housing (litter quality, type of litter, stocking density and drinking system). YOUSSEF (2011) noted that lignocellulose litter showed the lowest severity of foot pad lesions on dry and wet litter and chopped straw (dry) was associated with higher foot pad scores. Finally, there are factors related to diseases caused by various infections. However, since decades litter moisture is considered to be a leading factor causing FPD (JENSEN et al., 1970).

Therefore, distinct trials were conducted to find out the “critical” litter moisture content (that results in higher severity of FPD), to investigate the effects of litter type/floor heating, to quantify the impact of the dietary factors (surplus of electrolytes) and finally to test potential effects of a coccidial infection (wet litter as a consequence of an experimental infection) on the development and severity of FPD in young turkeys housed with or without floor heating.

Material and methods:

Today’s breeding companies and their multipliers offer a broad range of commercial layer varieties which differ mainly in shell colour, egg numbers and egg weight. If the demand of a given egg market is predictable on a long-term basis, the egg producers can choose a variety closest to market needs. Depending on these targets, the frequency of eggs in different grades can be optimized by choosing a commercial layer fitting to this demand. Table 1 indicates the range of average egg weight which may be found under identical conditions in a random sample test or on any farm.MAYNE et al. (2007). Also, the histopathological scoring for foot pads was recorded on a 7-point scale (0 = normal epidermis; 7 = more than one rupture or “ulcer” of the epidermis) according to MAYNE et al. (2007).

Experiment 1: “Critical” moisture content of litter

The control group was housed on dry wood shavings continuously, whereas each other group was divided into two equal subgroups and exposed daily for 4 or 8 h to different moisture contents in the litter (35 %, 50 % and 65 % DM) in adjacent separated boxes. These different moisture contents were achieved by adding water continuously as required. All turkeys were fed ad libitum an identical commercial pelleted diet. Foot pads were assessed weekly for external scoring and at the end of experiment for histopathologically investigations.Experiment 2: Litter type and floor heating

The first 2 groups were kept on wood shavings (35 % moisture) with and without floor heating, the other 2 groups on lignocellulose (35 % moisture) with and without floor heating. Lignocellulose (Soft Cell®), made of natural lignocellulose which is processed into a soft and flexible material and is pelletized afterwards.The electrical floor heating system supplied with adjuster to control the temperature was used. Half of birds in each group were housed for 8 h/d in adjacent separate boxes where the litter was kept clean and dry (85 % DM) throughout the experiment. The temperature at litter surface varied at 35 °C in boxes with floor heating vs. 25 °C in ones without floor heating. All turkeys were fed ad libitum an identical commercial pelleted diet. Dust concentrations (PM10) were measured during the whole experimental period by using Air- Chek sampler (LISTED 124 U, Model: 224- PCXR8, SKC Inc. Pennsylvania, USA).Experiment 3: High dietary electrolyte levels with and without floor heating

All birds were housed on wood shavings. Two groups were fed on normal dietary levels of electrolytes (1.7 g Na; 8.5 g K and 1.5 g Cl /kg), while the other two groups were fed on a diet with about doubled levels (3.3 g Na; 15.7 g K and 3.2 g Cl /kg). For each dietary treatment, half of the birds were exposed to floor heating. Half of birds in each group (n = 10) was exposed daily for 4 h in adjacent separate boxes on wood shavings litter with a “critical” moisture content (35 % water/ i.e. 65 % DM). In each experiment, foot pads were assessed weekly macroscopically and at d 35 for histopathological scores.Experiment 4: Experimental coccidial challenge with and without floor heating

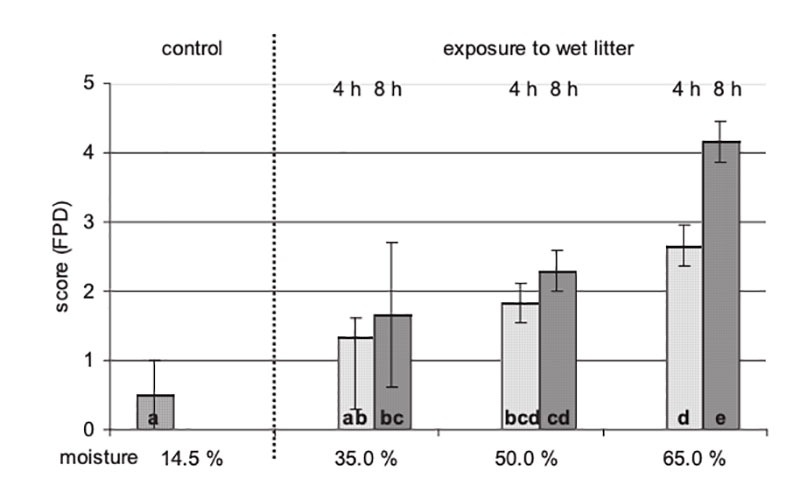

Two consecutive trials were done. All birds were fed ad libitum an identical pelleted diet without anticoccidia. The first 2 groups were kept on dry wood shavings with or without floor heating; the other 2 groups were housed on wet wood shavings litter with critical moisture content (35 %) with or without floor heating. Only two birds in each group were experimentally infected at d 14 of life with E. adenoeides (~50,000 oocysts/bird) nominated as seeder birds and/or primary infected birds. Foot pads were assessed weekly for external scoring and at d 42 of life for histopathological scoring. The number of oocysts was determined repeatedly in the excreta of the primary infected birds as well as from the pooled excreta samples of the other ones (nominated as secondary infected birds).Results: 1. In the first experiment, it was assumed that the “critical moisture content” for the development of FPD lesions is about 35 % litter moisture content. Furthermore, doubling exposure time (4—8 h) led to only slightly increased severity of FPD for the low litter moisture contents (35 and 50 % moisture) and a higher rise for the wettest litter treatment (65 % moisture) at the end of the trial.

External foot pad scores of young turkeys at the end of the experimental period

(d 35) in relation to different exposure times to varying litter moisture (Mean ± SD);

lowercase letters indicate significant differences with p < 0.05 between the groups

(ABD EL-WAHAB et al., 2012a)

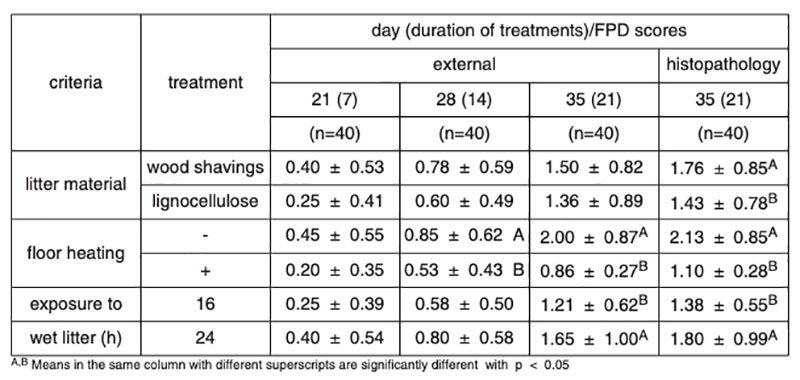

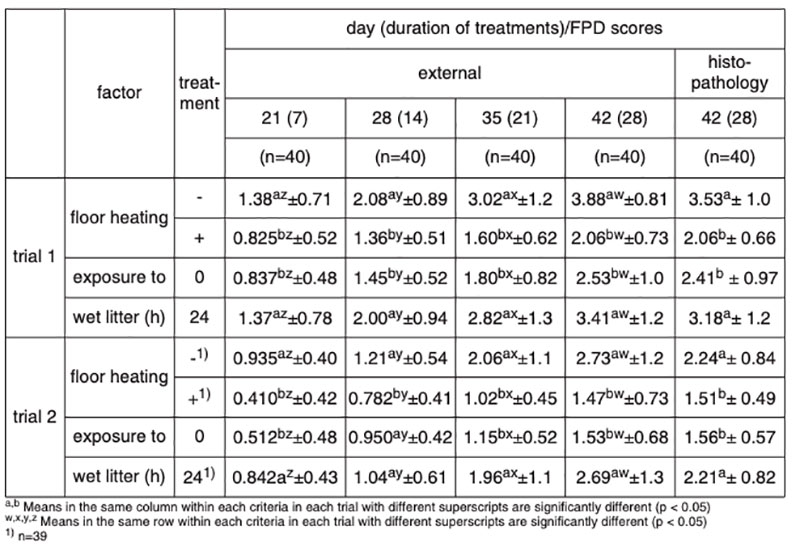

2. In the second experiment regarding litter material, lignocellulose resulted in significantly lower histopathological FPD scores (1.43 ± 0.78) compared with wood shavings (1.76 ± 0.85). Using floor heating led to significantly lower FPD scores (0.86 ± 0.27) compared with groups without floor heating (2.0 ± 0.87). At using floor heating no significant differences were found between wet wood shavings and wet lignocellulose.

Table 1: Development of external and histopathological foot pad scores influenced by three

factors (Mean ± SD by ABD EL-WAHAB et al., 2011a)

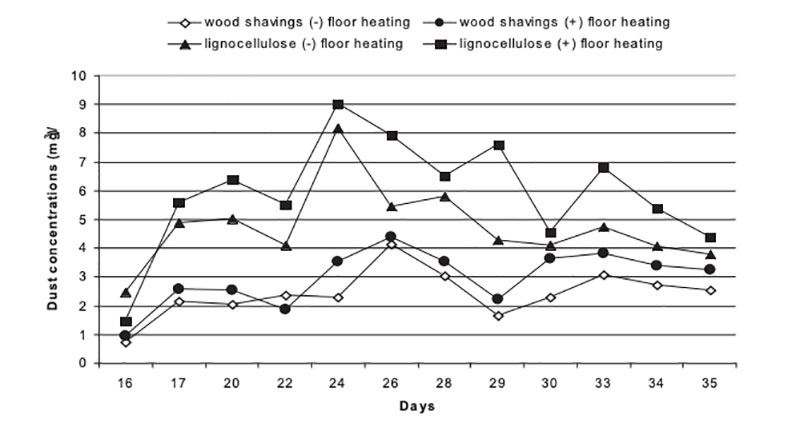

Moreover, in pens littered with lignocellulose highest amounts of dust compared with wood shavings was observed.

Figure 2. Dust concentrations in the air (mg/m³

; 75 cm above the litter surface) inside the

pens (litter moisture 35 % for 24 h/d) during the experimental period

(ABD EL-WAHAB et al., 2011a

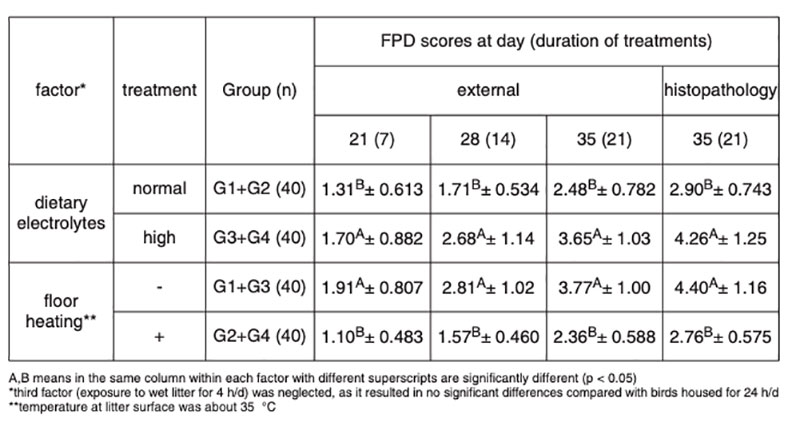

3. In the third experiment, high dietary electrolytes increased the severity of FPD (3.65 ± 1), whereas floor heating decreased it significantly (2.36 ± 0.5) due to higher DM content in the litter. Combining low electrolyte levels with the floor heating system reduced the severity of FPD by about 60 %, compared to high dietary electrolytes levels without floor heating.

Table 2: External and histopathological foot pad scores (results of two factors variance

analyses, mean ± SD) during experimental period (ABD EL-WAHAB et al., 2011b)

Furthermore, using floor heating resulted in higher water:feed intake ratios (2.9 and 3.6) for birds fed normal or high dietary electrolytes vs. ratios for birds housed without using floor heating and fed normal or high dietary electrolytes (2.3 and 2.8).

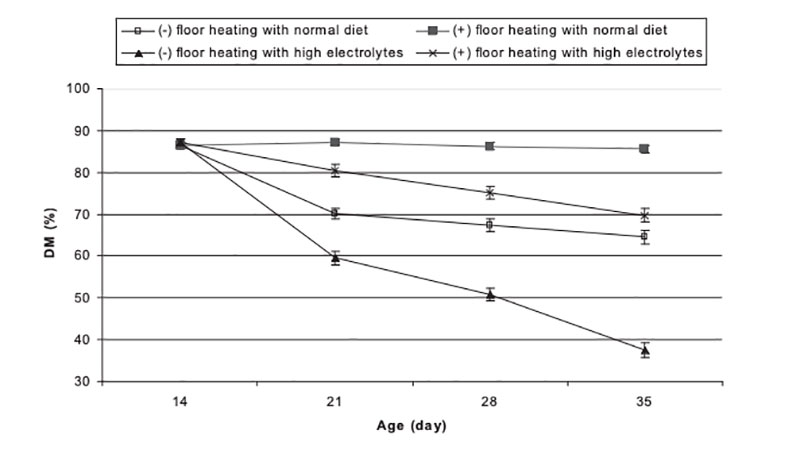

Figure 3: DM contents (%) of the litter in pens without adding water (dry litter)

(ABD EL-WAHAB et al., 2011b)

4. In the fourth experiment, using floor heating resulted in significantly lowered FPD scores (2.06 ± 0.735; 1.47 ± 0.734; trials 1/2) compared with groups housed without floor heating (3.88 ± 0.812; 2.73 ± 1.25) in both trials. Birds exposed continuously to wet litter (35 % moisture) showed significantly increased FPD scores (3.41 ± 1.23; 2.69 ± 1.34) compared with the group not exposed to wet litter (2.53 ± 1.00; 1.53 ± 0.683).

Table 3: Development of external and histopathological foot pad scores two factor variance

analyses; mean ± SD (ABD EL-WAHAB et al., 2012b)

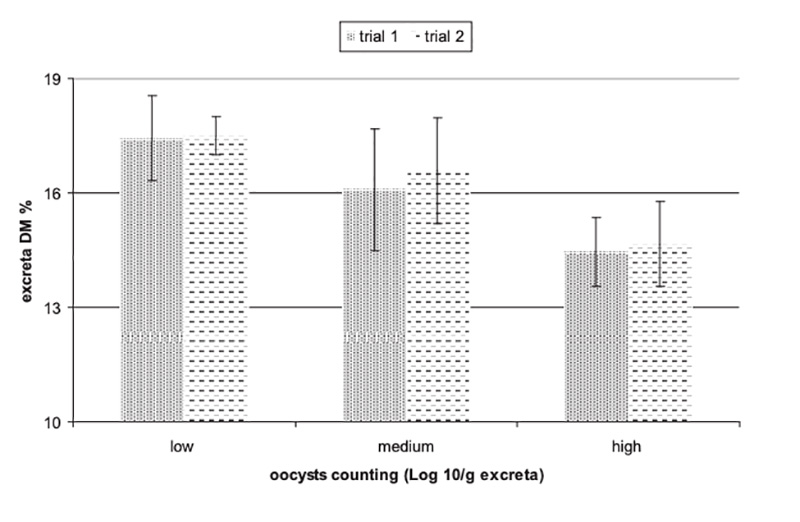

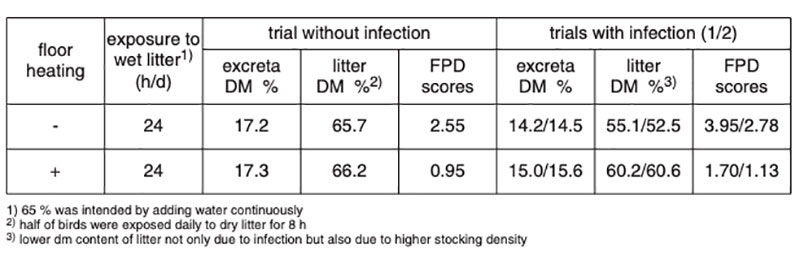

The coccidial infection resulted in markedly lowered DM contents of excreta and litter (14.8 and 58.0 %, 15.1 and 57.6 % in both trials, respectively) in the groups exposed to wet litter without using floor heating. However, in both trials using floor heating resulted in the highest mean DM content of litter (85.1 and 85.0 %) and also the highest body weights (2693 and 2559 g) despite coccidial infection. Furthermore, Figure 4 provides more details on the effects of the severity of coccidial infection on mean DM content of excreta, the oocyst count “Log 10/g excreta” classified into 3 categories (numbers 0-2 = low; numbers 2-3.5 = medium and numbers 3.5-5 = high). Accordingly, in both trials at low counts of oocysts in excreta there were significantly increased DM content of excreta (17.4 % ± 1.11 and 17.5 % ± 0.568) vs. (14.5 % ± 0.900 and 14.6 % ± 1.10) for the high oocyst count in excreta was observed.

General discussion:

A low prevalence and severity of foot pad dermatitis (FPD) are of great concern for many producers regarding both the bird’s performance and product quality. The cause of FPD – as demonstrated here in each experiment – seems to be very complex.Figure 4: Counts of oocysts in the pooled excreta related to dm content (%, mean ± SD)

throughout the experimental period, the oocyst count “Log 10/g excreta” was

classified into 3 categories (numbers 0-2 = low; numbers 2-3.5 = medium and

numbers 3.5-5 = high (ABD EL-WAHAB et al., 2012b)

Exposure to wet litter

Proper dry litter conditions are a prerequitite for healthy foot pads. Many authors have found positive correlations between litter quality, particularly moisture and the incidence of FPD (HARMS and SIMPSON 1977; EKSTRAND et al. 1997; YOUSSEF 2011). Pure water (without excreta) alone in the litter is sufficient to produce severe lesions (MAYNE et al. 2007; YOUSSEF 2011). The effect of exposure time was on focus for the first time in this experiment. However, an exposure of birds to wet litter containing 35 % moisture for only 4 h/d during the first week of experiment was definitely enough to induce a significant increase in external and histopathological FPD scores thus indicating that the critical moisture content in the litter may be at least 35 %. By doubling the time of exposure (8 h) the severity of FPD was only slightly increased compared with those birds exposed to only 4 h, primarily for lower litter DM content. This could be explained by the fact that standing on wet litter brings the feet in constant contact with moisture and has been suggested to cause the foot pad to soften and become more prone to damage, predisposing the bird to developing FPD (JENSEN et al., 1970). But a critical question should be allowed: is the litter really the right focus? The litter is a mixture of bedding materials with increasing amounts and proportion of excreta (KAMPHUES et al., 2011). At the end of the fattening period the proportion of excreta will exceed 90 %, it means that less than 10 % is coming from the litter material. Thus, it is presumably more important that the excreta (faeces and urine) release the water, which is transferred to the air and by the latter out of the barn. Under this aspect the ventilation in the barn is worth to be underlined. Then the question will arise on all factors that could influence the water release from the excreta and from the mixture of litter with excreta and the transfer to the air above the litter surface. It is well known that “layers of excreta” on the litter surface impair the process of drying markedly. Thus in future experimental studies, it should be tested what are the main influences that impair/prevent or facilitate the water release from fresh excreta.Litter type

Only in one experiment lignocellulose was used as a litter material. It was found that at 35 % moisture content, lignocellulose was accompanied with significantly lower FPD scores compared with wood shavings. Nevertheless, from economical point of view, lignocellulose will never be used for the whole fattening period (20 weeks of turkeys), due to its high costs (12.5 kg/m² = 5 €/m²). But some people hypothesize that very good litter conditions in the rearing period would give advantages for the following fattening period. So, may be that using lignocellulose in the rearing period and wood shavings in the fattening period could be a solution acceptable from economical point of view. However, ABD EL-WAHAB et al. (2011, unpublished data) observed that lignocellulose in the first 6 weeks of rearing turkeys caused significantly lower FPD scores compared with wood shavings. Nevertheless, with shifting from lignocellulose (6 weeks rearing period) to wood shavings until end of the fattening period (20 weeks) did not result in marked differences in comparison to those housed continuously on wood shavings. Furthermore in a another study, ABD EL-WAHAB et al. (2011, unpublished data) found that lignocellulose is much better regarding health of foot pad than straw-granulate pellets (new bedding material) in the first five weeks of rearing turkeys. But due to high costs of lignocellulose and due to some technical problems during its processing which lead to increase airborne dusts in poultry houses seem to be the most limiting factors for using lignocellulose as litter material in the field. Therefore, lignocellulose could be not suitable as a litter material for rearing turkeys but a promising bedding material for rearing broilers due to fewer amounts of lignocellulose littered and shorter rearing period in comparison to turkeys. Therefore, lignocellulose could be a suitable litter bedding material for broiler (rearing period 35 days only) as well as due to small amount of lignocellulose used as a litter.Floor heating technique

Independent of further factors (type of litter, diet composition, artificial infection) the use of floor heating resulted in desirable changes regarding prevalence and severity of FPD. Up to now, these effects are supposed to be related to the drier surface of the litter. By using floor heating in the own experiments, distinct interesting interactions could be demonstrated. For example, in spite of high sodium and potassium levels in the diet no detrimental effects occurred regarding litter quality and/or foot pad health. Although the water intake increased – when birds were housed with floor heating – the litter had higher DM content at the end of the trial (d 35), indicating that the floor heating favoured markedly the release of water (transfer to the air). But in general for the first weeks of birds’ life, it could be a recommendable measure for the practice. Because in this early stage the birds need high ambient temperature, high protein diets (often high potassium levels due to high proportion of soybean meal). Nevertheless, there is a need to look on “side effects” of floor heating technique. For example, as it was observed in field studies that it seems to be a trend for higher airborne dust levels in barns when floor heating comes in use.Diet composition

As demonstrated in details by YOUSSEF (2011), there are many ways by which the diet could interfere with FPD “a wide spread problem in poultry flocks”. There are changes in the diet that could increase the risk of FPD, but also there are some other dietary strategies that could help to reduce or minimize the prevalence and severity of FPD (adding zinc and/or biotin in a surplus). In diet formulation it is easy to achieve a low Na content but using normal protein sources often results in K levels >10 g/kg diet.In the present investigations it was demonstrated that surplus levels of dietary electrolytes did not result in detrimental effects on foot pad health when floor heating was in use. Thus, by using floor heating we will not realize those mistakes of diet composition/formulation. But testing the diet composition, should not let us neglect the potential role of coccidiosis or – from the feed production point of view – the correct use/adding of an effective coccidiostat. However, the emergence of resistance to coccidiostats, consumer demand for using fewer feed additives, and European Union Regulations (withdrawal of antibiotic feed additives as a precautionary measure) might restrict the use of coccidiostats (EUROPEAN COMMISSION REGULATIONS, 1997). If this happens, alternative strategies should probably be introduced to minimize the adverse effects of coccidia on animal health and production. Additionally, due to misdosing and/or inefficient anticoccidial additive in the diet, the excreta and bedding material will be markedly influenced by the coccidial infection resulting in higher scores of FPD. Thus, the consequences of own experimental studies are that in case of increased FPD problems/prevalence a chemical analysis of the diet (misdosing of nutrients/minerals) is recommended, but also counting the oocysts in the excreta is necessary to detect “sub-clinical coccidiosis”. In field studies it seems to be worth to check concomitantly the FPD scores and the counts of coccidial oocysts. In the experiment 4, there was an interesting relation between the counts of oocysts in the excreta and the DM content of excreta that could be used in the field comparison (without neglecting the other enteric infections such as clostridia which could have identical effects and consequences). But here, the artificial infection with coccidia was chosen to demonstrate what could happen in a consequence of misdosing of additives or confounding diets (with/without coccidiostat).

Role of coccidiosis

To simulate a condition that could happen in a field, two replicated trials were done. It was observed that oocyst numbers in the excreta were closely correlated with changes in excreta quality. Experiment 4 provides a major great detail on the effects of the intensity of coccidia infection on mean excreta DM. The oocyst counting “Log 10/g excreta” was classified into 3 categories (numbers 0-2 = low; numbers 2-3.5 = medium and numbers 3.5-5 = high). Accordingly, it was observed that high oocyst numbers in excreta was accompanied with a significantly lower excreta DM content. Thus, coccidial infection acts additively on excreta/litter moisture contents. Additionally, combination of floor heating and dry litter resulted in markedly reduced oocysts shedding in the seeder birds “primary” as well as in secondary infected birds. Interestingly, medium oocyst counting “Log 10/g excreta” of secondary individual infected birds resulted in the highest FPD scores for the same birds and the high oocyst counting “Log 10/g excreta” of secondary individual infected birds did not correlate with the FPD scores of the same birds.Using floor heating for infected birds resulted in significantly lower FPD scores compared with groups housed without using floor heating. Despite forced watery excreta due to coccidial infection, the litter became drier when floor heating was in use. Therefore, floor heating is likely to be highly effective in reducing the development and severity of FPD. However, the highest oocysts in the chymus were found in the group housed on dry litter with using floor heating. This is an interesting observation that is up to now not understood. Additionally, it was observed that in similar factors (housing and feeding) the worst effect on foot pad was due to artificial infection with coccidia either with or without using floor heating (Table 4).

Table 4: Comparison between experimentally infected and not infected birds with coccidia

on DM contents (%) of excreta and litter as well as on FPD scores at 35 d of life in

young turkeys

Conclusions

The key point is that the prevalence and severity of FPD were clearly affected by the litter quality. Improving the general standards of rearing, considering housing facilities, equipment, management and stockman ship should be considered as these factors are mainly related to the animals’ welfare. As demonstrated in these experimental studies litter quality has a great impact on the bird’s welfare. The first marked increase of FPD lesions was observed after one week of exposure for 4 h/d at 35 % litter moisture with increasing severity of FPD for higher moisture contents. Both factors (moisture content/exposure time) significantly and additively influenced severity of FPD. Floor heating, even with wet litter (35 % moisture) and independent of litter type, resulted in reduced severity of FPD compared with birds in pens without floor heating. ABD EL-WAHAB et al. (2011a,b) observed that the significant effect of using floor heating on FPD scores could be due to the litter becoming dry as fresh litter or could be due to floor heating leading to warm foot pads (Table 4) causing vasodilatation of the blood vessels, increasing the blood flow to promote healing. The principle of the warming effect on blood flow in humans was stated by NISHA (2003). On the other hand, with the absence of floor heating the litter is quite cool and might lead to blood vessel constriction resulting in a cold-wet foot pad. The heat source in turkey houses hangs above the pens; so the upper surface of litter becomes warm but the colder, deeper litter eventually moves to the top. In addition, using lignocellulose as a litter material resulted in lower FPD compared with wood shavings. However, lignocellulose will never be used for the whole fattening period (20 weeks), due to its high costs (12.5 kg/m2 = 5 /m2). High levels of electrolytes increased the severity of FPD significantly. Despite of forced water intake the litter became drier when floor heating was in use. Doubling the electrolytes levels in the diet increased the FPD scores by 50 % compared with normal levels. Using floor heating reduced the FPD scores by 40 %. Coccidial infections led to watery excreta and a poor litter quality and hence resulted in significantly increased severity of FPD which can be overcome by using floor heating. In the puzzle of factors that could result in FPD, here experimental studies were done to demonstrate diverse field relevant interactions. A lot of exact data were generated that might be used for epidemiological studies (for example, the value/range of critical moisture content in the litter). But the main result and experience of the four own different experiments is whenever you change one factor of the above called “puzzle” – willing or not – you change the parameters and findings in another part of the puzzle. It is the time to consider all factors in the puzzle (in a more holistic way?).References

In this paper, the results of four original articles published or accepted for publication in international journals are summarized:1. Abd El-Wahab A., Visscher C. F., Beineke A., Beyerbach M. and Kamphues J. (2011a): Effects of floor heating and litter quality on the development and severity of foot pad dermatitis in young turkeys. Journal of Avian Diseases 55:429-434

2. Abd El-Wahab A., Visscher C. F., Beineke A., Beyerbach M. and Kamphues J. (2011b): Effects of high electrolyte contents in the diet and using floor heating on development and severity of foot pad dermatitis in young turkeys. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition. (Article first published online: 13 OCT 2011, DOI: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2011.01240.x).

3. Abd El-Wahab A., Visscher C. F., Beineke A., Beyerbach M. and Kamphues J. (2012a): Experimental studies on the effects of different litter moisture contents and exposure time to wet litter on development and severity of foot pad dermatitis in young fattening turkeys. Arch.Geflügelk., 76 (1). S. 55–62, 2012, ISSN 0003-9098.

4. Abd El-Wahab A., Visscher C. F, Wolken, S., Reperant, J-M., Beineke A., Beyerbach M. and Kamphues J. (2012b): Foot pad dermatitis and experimentally induced coccidiosis in young turkeys fed a diet without anticoccidia. Poult. Sci. March 2012 vol. 91: 3 pp 627-635.

A complete list of references from the doctorate thesis entitled “Experimental studies on effects of diet composition (electrolyte contents), litter quality (type, moisture) and infection (coccidia) on the development and severity of foot pad dermatitis in young turkeys housed with or without floor heating” may be obtained from the supervisor and corresponding author:

Zusammenfassung

Experimentelle Untersuchungen zu Auswirkungen der Futterzusammensetzung (Elektrolytgehalt), der Einstreuqualität (Art, Feuchte) und einer Kokzidieninfektion auf die Entwicklung und den Schweregrad der Fußballenerkrankung junger Puten bei unterschiedlicher Haltung (ohne/mit Fußbodenheizung)Sowohl Vorkommen als auch Schweregrad der Fußballenerkrankung (Foot Pad Dermatitis, FPD) werden maßgeblich von der Qualität der Einstreu bestimmt. Es ist bekannt, dass es sich bei dieser Störung um ein multifaktorielles Geschehen handelt, in dem die Haltung, die Fütterung, das Management, aber auch Infektionen eine maßgebliche Rolle spielen.

Ein erster deutlicher Anstieg der FPD-Läsionen war nach einwöchiger Exposition für 4h/d bei 35% Feuchtigkeit der Einstreu zu beobachten. Sowohl die Feuchtigkeit als auch die Expositionsdauer hatten einen signifikanten, d.h. additiven Effekt auf den Schweregrad der FPD. Der Einsatz einer Fußbodenheizung führte auch bei feuchter Einstreu und unabhängig vom Einstreutyp im Vergleich zu Tieren, die ohne Fußbodenheizung gehalten wurden, zu einem verringerten Schweregrad der FPD. Nach eigenen früheren Untersuchungen kann unterstellt werden, dass der signifikante Effekt der Fußbodenheizung auf die Ausprägung der FPD Scores darauf zurückzuführen sein könnte, dass die Einstreu trockener ist oder dass es aufgrund der Wärmeeinwirkung auf die Fußballen (Table 4) dort zu einer Vasodilatation kommt. Der hierdurch gesteigerte Blutfluss könnte den Heilungsprozess beschleunigen. Das Prinzip des Wärmeeinflusses auf den Blutfluss wurde bereits von NISHA (2003) beim Menschen festgestellt. Auf der anderen Seite ist die feuchte Einstreu ohne Fußbodenheizung

kühler und könnte zu einer Vasokonstriktion mit daraus resultierenden kühlen sowie feuchten Fußballen führen. Da die Heizquelle in Putenställen über den Tieren hängt, wird die Oberfläche der Einstreu wärmer, aber der kältere, tiefer gelegene Anteil wird unter Umständen auch wieder an die Oberfläche gekehrt. Weiterhin führte die Benutzung von Lignozellulose als Einstreumaterial im Vergleich zu Hobelspänen zu einer geringeren Ausprägung der FPD. Aufgrund der hohen Kosten (12,5 kg/m2 = 5 /m2) wird Lignozellulose kaum während der ganzen Mastperiode (20 Wochen) genutzt werden können. Hohe Gehalte an Elektrolyten im Futter erhöhten den Schweregrad der FPD signifikant. Trotz forcierter Wasseraufnahme war die Einstreu trockener, wenn eine Fußbodenheizung genutzt wurde. Eine Verdopplung der Elektrolytgehalte im Futtermittel erhöhte die FPD Scores im Vergleich zu normalen Gehalten um 50%. Die Nutzung der Fußbodenheizung reduzierte die FPD Scores um 40%. Die experimentelle Infektion mit Kokzidien führte zu wässrigen Exkrementen und einer entsprechend schlechten Einstreuqualität. Dadurch erhöhte sich der Schweregrad der FPD signifikant, was ebenfalls bei Nutzung der Fußbodenheizung verhindert werden konnte. In dem „Puzzel“ des multifaktoriellen Geschehens um die FPD wurden hier Studien durchgeführt, um diverse praxisrelevante Einflüsse nachzustellen. Es wurde eine große Anzahl exakter Daten gewonnen, die für epidemiologische Studien benutzt werden können (zum Beispiel einen Wert/Bereich, ab dem von einer „kritischen Einstreufeuchte“ gesprochen werden kann). Das wesentliche Ergebnis der durchgeführten Untersuchungen ist, dass aufgrund der vielfältigen Interaktionen bei der Entstehung der Fußballenerkrankungen ein ganzes Spektrum möglicher Einflüsse differentialdiagnostisch bedacht werden muss. Es ist angebracht, alle Zusammenhänge zu betrachten.