H.-H. Thiele (LOHMANN TIERZUCHT GmbH), G. Díaz (Biomix S.A.) and L. Armel Ramirez (Pronavicola S.A.)

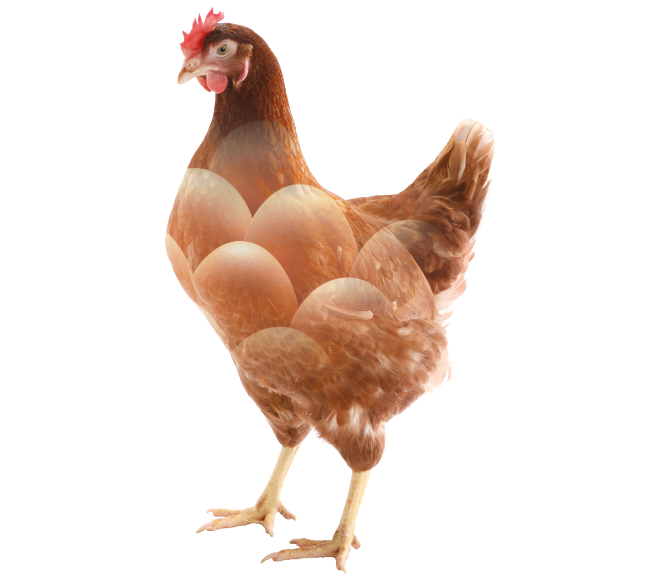

During their lifetime, modern laying hens produce a lot of eggs, hopefully “well packed” for handling as hatching eggs or shell eggs for human consumption. Only eggs harvested „wellpacked“ from the nests (or cages) will add to farm income and meet the demands of hatcheries, processing plants, egg traders and consumers, whereas eggs with insufficient shell quality seldom recover the production cost and may be a complete loss.

selection for improved shell stability is an integral part of continuing efforts to enable modern laying hens to produce more eggs with good shell quality over a longer period of time. egg producers and feed manufacturers should enable the birds to express their genetic potential, providing an adequate nutrient supply with all necessary raw minerals for proper shell formation. Attention to optimal nutrition is recommended throughout the laying period and is becoming even more significant since as the laying period of flocks is being extended. with increasing age and cumulative number of eggs produced, the ability of hens to produce eggshells of good quality tends to decline. This is partly due to the exhaustion of calcium metabolism of the bone, but can also occur as a result of liver damage. Acute fatty liver syndrome or chronic congestion of the liver will accelerate the loss of shell stability with age.

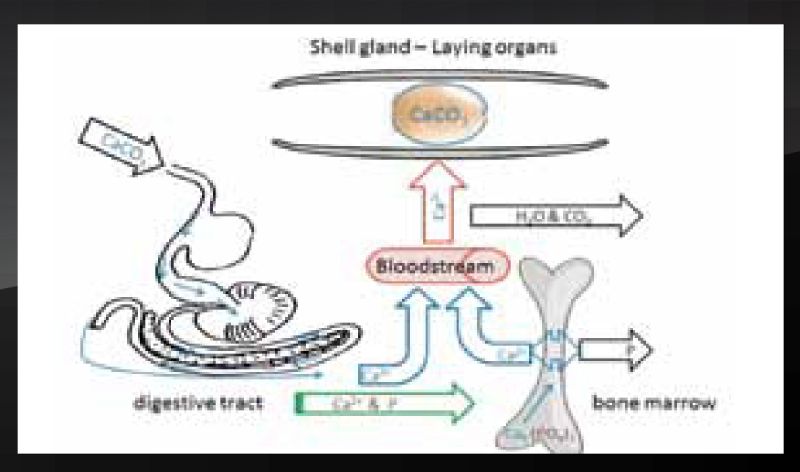

The shell of a hen‘s egg consists up to 90-95 % of calcium carbonate which is embedded in a protein matrix that determines the strength of the egg. The eggshell is made essentially from lime, which is made available either from the daily feed supplied or from the long bones, especially the medullary bone marrow. The calcium reservoir of this bone is formed with the onset of sexual maturity until shortly before the onset of egg production. The calcium in the bone is bound to phosphate. How much of the lime actually used to form an eggshell comes from the recent dietary intake and how much from the bone varies and depends on the availability of the latter at the time of shell formation. since the hens have only limited reserves of calcium in their bones, this must be supplemented with the daily dietary intake. Today’s commercial laying hens lay an egg almost every day and therefore require about 4-5 grams of calcium per day. In order to support the complex process of eggshell formation, the hens should also be supplied with sufficient phosphorus and vitamin D3.

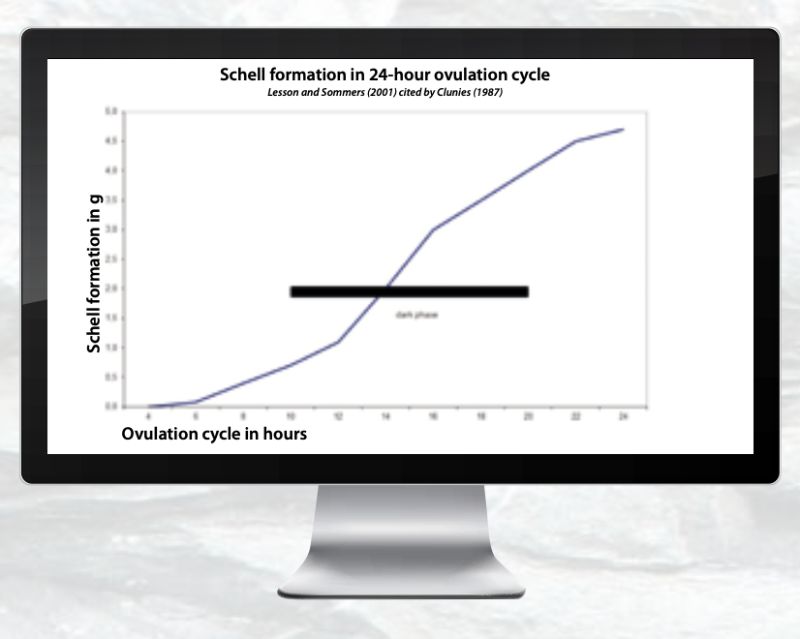

Figure 1: shell formation in a 24-hour ovulation cycle (Clunies (1987) cited by Leeson and Summers (2001))

The process of eggshell formation takes place mainly during the hours of the night. The most intense period of shell formation is about 12-18 hours following the laying of an egg. The intensity reaches its peak at 18 hours after an egg is laid and starts to decline again before the next egg is laid. During this time, enough lime should be available from the gastrointestinal tract. since the retention period of ingested feed in a chicken’s digestive system is relatively short, i.e. about 3-4 hours, it is important to feed the bird with lime at the right time. scientific studies have shown that laying hens with ad libitum access to lime have a particularly high appetite for lime in the last 5-6 hours of daylight. Apparently, these birds instinctively know when they need more supply.

At night, there is a cyclical increase in the female sex hormone oestrogen which increases the solubility and transportability of calcium. If no lime is available in the gastrointestinal tract during this time, the reserves in the bone would be mobilized. To prevent this, the structure of the lime supplied should not be too fine so that it cannot be dissolved quickly and then excreted by the hen during the day, before being needed and used.

The benefits of feeding coarse lime (1.5 to max. 4 mm particle size) in the afternoon or evening hours have been demonstrated repeatedly. By doing so, the amount of the calcium derived from the feed is maximized and the calcium metabolism of the bone is minimized. without adding to feed cost, this feeding program combines three advantages: reduced phosphorous level in the feed (saving limited resources), less metabolic work for the hens (and maintenance of bone strength), and significant reduction of phosphorus excretion. The reduced daily mobilization of calcium reservoir in the bones would reduce the phosphorus excretion.

lime fine < 0,5 mm

Diaz, 2008

lime coarse 1,5-2,5 mm

Armel, 2011 lime very coarse ≥ 4 mm

Armel, 2011

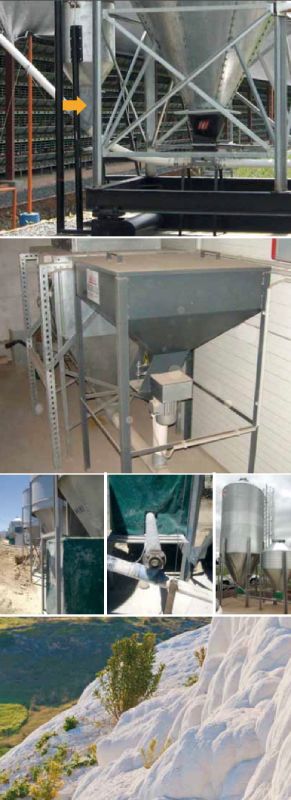

Armel, 2011 It is obvious that an optimally timed supply of lime is important for the maintenance of bone strength. If a laying hen extracts calcium from the reservoir of her bones during the night, the lime will not only be mobilized from the medullary bone, but also from the marrow of the structural bones. This reservoir cannot be restored during very long laying sequences, unlike the reservoir in the medullary bone marrow. The laying hen can only “repair the damage“ during laying pauses or moulting, which allows the lime to be stored in the marrow of the structural bones and practically rebuild the reservoir. A modern laying hen producing eggs in long “clutches”, has to utilize the reservoir of the bones almost daily, compromising the long-term bone stability and increasing the well-known risk of bone fractures. For optimal implementation of these findings, it would be necessary to provide two different feed mixtures: feed with lower calcium content and finer particles offered in the morning hours, feed with a higher lime content and coarse particle size during the afternoon and evening hours. where it is impossible or too difficult to implement this recommendation in practice, a significant effect can be achieved by supplementing the single ration with coarse lime in the afternoon and evening feedings. experience in practice has shown that this not only improves shell stability, but also bone stability and the general health of laying hens. Mini silos to supplement the feed and provide the right dosage of lime at the right time are becoming increasingly popular worldwide.

Figure 2: Simplified representation of the egg – shell formation

As a general rule, we must assure that all essential components of the feed will become available for each hen, i.e. we must avoid segregation of feed components between feed mill and the hens. This applies to all nutrientrelevant raw materials as well as minerals and vitamins. A homogeneous good mash feed structure is the feed for the modern laying hen. with good feed quality, the use of fine or coarse lime is unproblematic. In case of pelleted or crumbled layer feed raw material components were mostly milled through a hammer mill which makes it difficult to add coarse lime. In this case lime must be added after pelleting; otherwise the lime content will have little value for the laying hen.

Dr. Hans-Heinrich Thiele

Photos: Armel (2011), Luykx (2012), Thiele (2014), Kruger (2014)