Photorefractoriness

Photorefractoriness is a natural physiological condition that differentiates broiler breeders and turkey breeders from egg-type breeders and commercial layers, particularly regarding their response to lighting. It is a phenomenon which needs to be understood before lighting patterns can be correctly designed for either broiler or turkey breeders. The condition has long been recognised in turkeys but has only recently been acknowledged in broiler breeders and, as a result, broiler breeder lighting recommendations have frequently been incorrect. It is worth noting that egg-laying hybrids no longer exhibited photorefractoriness and therefore have fewer constraints imposed on their lighting requirements.What is photorefractoriness? It is a long word that simply means the inability to respond to light, but more specifically the lack of a sexual response to an otherwise stimulatory daylength. All seasonalbreeding birds are hatched in a refractory state, termed juvenile photorefractoriness, which generally prevents them from breeding in their first year. The condition is dissipated in full-fed birds by exposure to about two months of short days; these are daylengths which are neutral in their ability to sexually stimulate an animal (note they are not negative) and are usually no longer than 9 hours. Birds, such as broiler breeders, that have their growth controlled by the feeding programme take longer to become photoresponsive. In nature, dissipation of photorefractoriness is achieved by the short days of winter, which allows the bird to commence breeding in the following spring. However, after prolonged exposure to stimulatory daylengths during the summer months, the birds again become unresponsive to light, a condition called adult photorefractoriness, and generally go out of production until they have gone through a second period of short days.

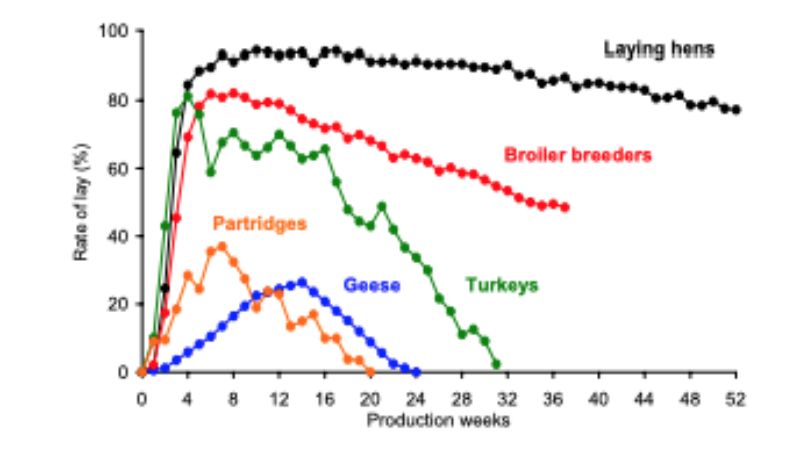

There are two forms of photorefractoriness: an absolute form, as seen in truly seasonal breeding birds like pheasants, partridges and geese, and a relative form, as exhibited by broiler and turkey breeders. In the absolute form, sexual development is severely retarded when birds are reared from hatch on long days, with some individuals never becoming sexually mature. For example, in a study in which red-legged partridge were reared from hatch on 16-hour days, the first bird did not lay its first egg until it was 68 weeks of age and 3 years later more than 60% of the birds were still infertile. In contrast, birds like broiler breeders and turkey breeders which show the relative form are only moderately (2 to 4 weeks) retarded by not being given a period of short days. Interestingly, the intense selection for egg numbers over the past 50 years has resulted in modern egg-laying hybrids no longer showing photorefractoriness. Whereas rates of lay in broiler breeders will typically be below 50% by 60 weeks of age (after about 36 weeks production) and egg laying in turkeys likely to have almost ceased after only 30 weeks, egg production in a flock of commercial egg layers may well still exceed 80% after 52 weeks in lay. Typical rates of lay for poultry species exhibiting the various forms of photorefractoriness are shown in Figure 1.

Flocks of broiler breeders or breeding turkeys will contain birds in varying states of photorefractoriness, especially at the end of the breeding cycle, with some continuing to be sexually active throughout the laying season, some back in lay after having paused and spontaneously resumed egg production whilst still on long days, and others having become photorefractory and not recommencing production without experiencing a period of short days or low light intensity to dissipate the refractoriness. The effects of photorefractoriness on egg laying in females are self evident, but similar effects occur with semen production in males; nature would not design a system in which one sex was fertile while the other was infertil

Figure 1. Typical rates of lay for laying hens (no photorefractoriness), broiler and turkey

breeders (relative photorefractoriness), and geese and partridges (absolute

photorefractoriness). Modified from Lewis (2009).

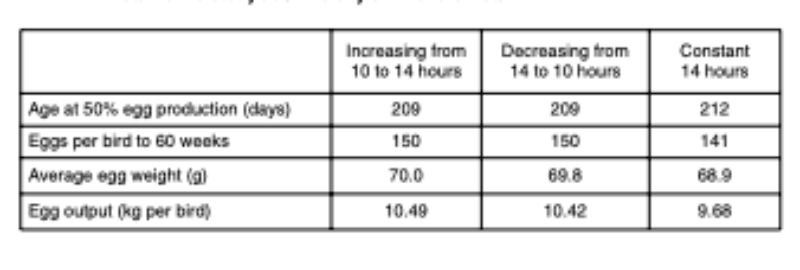

Broiler breeders

Rearing daylength and body weight influencesIt is essential to rear broiler breeders from an early age on short days, usually 8 or 9 hours, to ensure that all birds in the flock have had their juvenile photorefractoriness dissipated by the time they are transferred to long days (≥ 11 hours) at about 20 weeks of age. When broiler breeders are reared in open-sided or inadequately light-proofed buildings, and it is not possible for them to be given short days, it is advisable to simply let them experience the naturally changing daylengths, be the photoperiods increasing or decreasing. They should NOT be reared on a daylength equal to the expected longest natural daylength, as frequently recommended in breeder management manuals, because this will unacceptably delay maturity and reduce egg numbers. This may be the correct recommendation for egg-type stock; precocity will not be a problem even when birds are reared on increasing daylengths during the rearing period. The data in Table 1 from a study at the University of KwaZulu-Natal show that there were no significant differences in age at 50% egg production between broiler breeders reared on increasing or decreasing daylengths and others maintained on 14 hours from day old through to 20 weeks. However, the constant 14-hour birds laid fewer eggs, had a smaller average egg weight, and produced a lower total egg output than the birds reared under simulated naturallychanging daylengths. If broiler breeders are reared on 8-hour days and photostimulated at about 20 weeks, as routinely recommended, their sexual maturity will be 3 to 4 weeks earlier and their egg numbers and total egg output higher than birds reared on long days (Table 2). The indisputable answer to poor light control during the rearing period is to lightproof the buildings and not to tinker with the lighting programme.

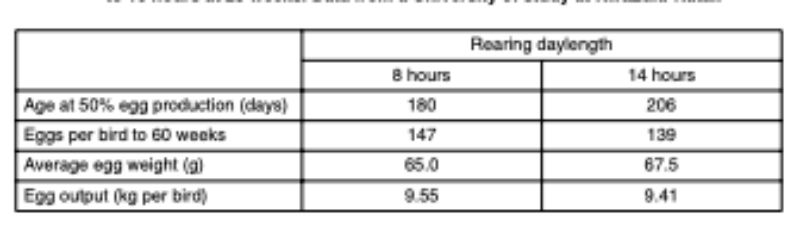

Table 1. Age at 50% egg production, egg numbers, average egg weight, and total egg output

to 60 weeks for broiler breeders reared to 20 weeks of age on a simulated naturally

increasing or decreasing daylength programme or maintained on 14-hour days.

Data from a study at University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Table 2. Age at 50% egg production, egg numbers, average egg weight, and total egg output

to 60 weeks for broiler breeders reared on 8-hour or 14-hour days and transferred

to 16 hours at 20 weeks. Data from a University of study at KwaZulu-Natal.

The significant reduction in growth achieved in broiler breeders by controlling their feed intake means that none will be responsive before 10 weeks of age and at least 18 or 19 weeks of short days will be required for all birds in the flock to become photoresponsive; a stark contrast to the two months required for full-fed photorefractory species to become photosensitive. Although the time taken for a flock of broiler breeders to complete the attainment of photosensitivity is much longer than the 5 to 9 weeks necessary for full-fed egg-type pullets, the commencement of photoresponsiveness in a flock and the point when all birds are able to respond occur at similar points on their growth curves (0.2 and 0.4 of mature body weight for the first and last birds to respond). If, for whatever reason, a flock of broiler breeders is underweight or uneven (CV more than 10%) when they would normally be transferred to long days, increases in daylength should be delayed by a week or so, depending on the size of the problem.

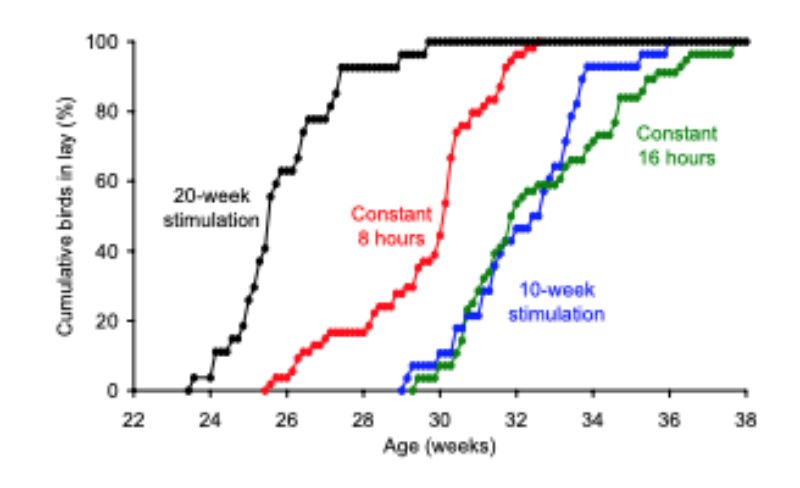

Photostimulation of a flock that contains under-weight, unresponsive birds will result in a marked delay in those particular birds’ sexual maturation and the development of a sexually uneven flock which will be difficult to manage. Even when a flock has satisfactory uniformity (CV less than 10%), photostimulation should still not be contemplated before the average body weight has reached 2.0 kg. Transferring broiler breeders with normal body weights to long days before they have had sufficient short days to fully dissipate juvenile photorefractoriness will result in delayed sexual maturation and sub-optimal egg production. This is because the premature photostimulation will result in the birds maturing as if they have always been on long days (refer Table 2). Research findings show that broiler breeders transferred from 8 to 16 hours at 10 weeks of age, when they were still photorefractory, matured at a similar age to birds maintained on 16 hours but two weeks later than non-photostimulated birds maintained on 8 hours and 7 weeks later than birds transferred to 16 hours at the more usual 20 weeks (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Effect of no stimulation (constant 8 hours), normal stimulation (20-week transfer

from 8 to 16 hours), premature stimulation (10-week transfer from 8 to 16 hours),

no short days (constant 16 hours) on sexual maturation in broiler breeders.

Data from a study at University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Although accelerating body weight gain in broiler breeders above normal breeder-targets of 2.0 to 2.2 kg speeds up the dissipation of photorefractoriness and enables them to be transferred to long days before 20 weeks, thus advancing sexual maturation and extending the laying cycle, the extra income derived from the increased egg numbers will invariably be cancelled out by the extra feed costs incurred in producing the faster growth and the increased production of un-settable, doubleyolked eggs (Lewis, 2006).

Daylength during lay

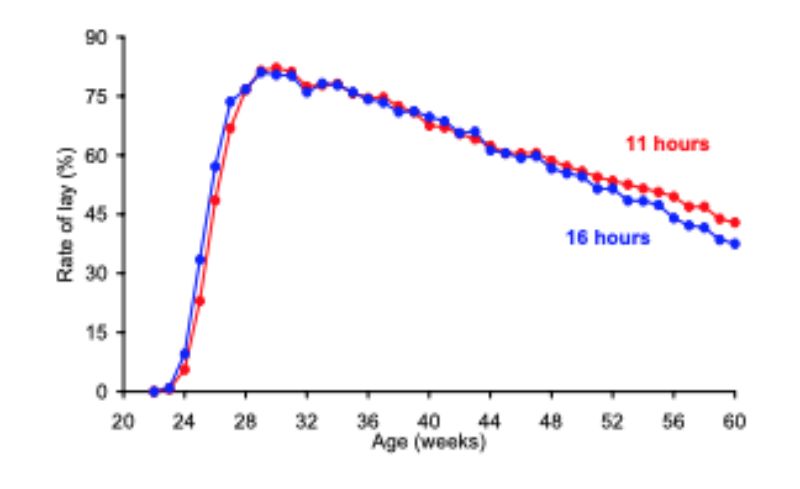

It has been traditional to give broiler breeders an initial transfer from 8 to 11 or 12 hours at 20 to 22 weeks followed by a series of increases to reach a maximum of 15 to 16 hours at about 27 weeks of age. However, recent research has shown that the onset of adult photo-refractoriness is advanced and rates of lay during the final three months of the laying cycle depressed when broiler breeders are provided with such long days. Studies conducted at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa have suggested that the ideal programme for broiler breeders, assuming body weights and uniformity are satisfactory, is to increase daylength from 8 to 13 hours at 20 weeks, either abruptly or incrementally, and to maintain this photoperiod for the remainder of the laying cycle. No benefits will be derived from giving further increases to 14, 15 or 16 hours, and shell quality will be depressed. Although 11 and 12 hours have been shown to give superior egg production to 16-hour days (Figure 3), egg-laying time occurs much earlier in the day under these daylengths and the increased proportion of eggs laid before the lights come on is likely to lead to an unacceptable number of eggs being laid outside the nest box. The risk of floor-laying is minimised by giving a 13-hour day.Figure 3. Rates of lay for broiler breeders transferred abruptly from 8 hours to 11 or 16 hours

at 20 weeks of age. Note the poorer terminal egg production for 16-hour birds.

Data from a study at University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Light intensity (illuminance)

The effect of light intensity during the rearing period on subsequent laying performance is minimal. Following an initial 2-3 days of bright light, the provision of an illuminance of at least 10 lux will be optimal and ensure that sufficient light is available for the satisfactory inspection of birds (as commonly required by welfare regulations). Whilst there is no interaction between the light intensity used during the rearing period and that given in lay, and there is no effect of light intensity on the rate of sexual development or total egg production so long as the light intensity at bird-head height is at least 10 to 15 lux, the recommended light intensity in the laying period is > 30 lux. This brighter-than-necessary recommendation is not made for biological reasons but to help minimise the number of eggs not laid in a nest box.Light colour and lamp type

There is no clear evidence that the performance of broiler breeders will be increased by using other than white light, that ultraviolet light provides any benefit, or that any one particular type of lamp is superior to any other. Whilst fluorescent lamps are currently the most economic method of lighting, LED lamps will undoubtedly be the method of the future.Conclusions

- Unlike egg-type hybrids, broiler breeders exhibit photorefractoriness.

- Restricting growth to a 2.0 to 2.1 kg average body weight at 20 weeks delays the acquisition of photosensitivity until at least 18 or 19 weeks of age.

- Rear on 8-hour daylengths to quickly dissipate juvenile photorefractoriness.

- Do not maintain birds on constant long daylengths during the rearing period in open-sided houses; simply accept the naturally changing daylengths.

- Photostimulate at 20 to 21 weeks and at a mean body weight of 2.0 to 2.2 kg provided the CV is no higher than 10%. Delay photostimulation if the CV is above 10%.

- Increase daylength from 8 to 13 hours abruptly or initially to 11 hours followed by weekly increments of 30 minutes to a 13-hour maximum.

- Maintain 13 hours throughout the laying period; longer daylengths will result in an earlier onset of adult photorefractoriness, poorer terminal rates of lay, and inferior shell quality.

- Use a light intensity of at least 10 lux in the rearing period and at least 30 lux in the laying period (to minimise floor eggs).

Turkey breeders

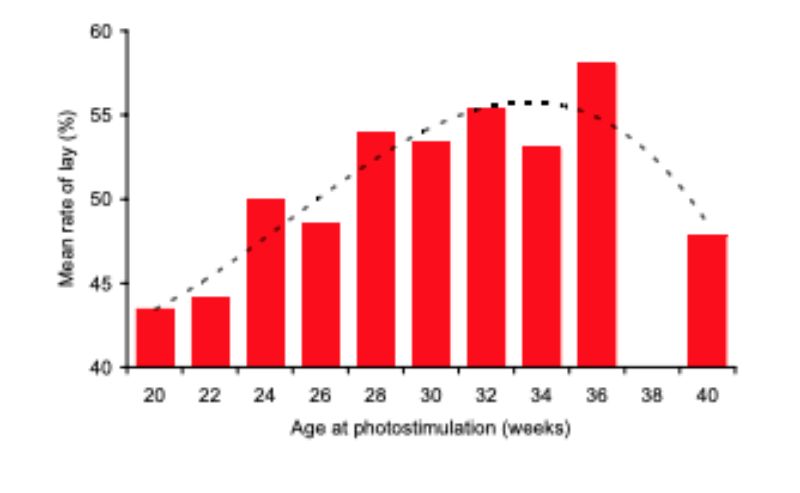

DaylengthTurkey breeders are not normally control-fed during the rearing period and so, unlike broiler breeders, require only two to three months of short days to dissipate juvenile photorefractoriness. However, because the optimal economical age for the start of egg-laying is 32 to 34 weeks of age (Figure 4), turkey breeders must either be reared on naturally long days or given 14-hour artificial daylengths for the first 3 months of life to slow down their acquisition of photosensitivity; without this period of long days they will commence egg-laying too soon. After the initial natural lighting or artificial long days, it is typical for the daylength of females to be progressively reduced to 6 hours by about 18 weeks and to be maintained at this length until it is increased to 14 hours between 30 and 32 weeks of age. The transfer to long days is made abruptly to ensure a uniform rate of sexual development and the facilitation of timely artificial insemination. Accordingly, the period between photostimulation and peak rate of lay in turkeys is shorter than in either laying hens or broiler breeders (see Figure 1). Although egg production is maximised, as in broiler breeders, by a 13-hour day, many turkeys are kept in poorly light-proofed buildings and longer daylengths should be provided to minimise the effects of decreasing natural daylengths after mid-summer.

Turkey males are also given a pre-breeding period of short days, but these are usually longer than those given to females, such as 10 to 12 hours. However, there appears to be no biological reason for them not being given the same daylength as females. It is probably a case of continuing to do what has always been done, because males were traditionally reared in open-sided pole barns. Males are generally slower maturing than females, so they are transferred to 14-hour days 4 to 6 weeks earlier than the females to synchronise sexual maturation.

Light intensity (illuminance)

It has been conventional to rear turkey breeders on a relatively bright light of 50 to 60 lux during the pre-breeding period to provide an intensity contrast between the desired 6-hour daylength and any natural light that may be infiltrating a poorly light-proofed building. However, the correct course of action is to make the rearing facilities lightproof during this period and not to hope that the turkeys will ignore the extraneous light; any unwanted light during the 18-hour ‘night’ is likely to have a detrimental effect on subsequent egg numbers. If the brighter light intensity is provided to stimulate activity during the short day, then this must be in addition to the provision of adequate light-proofing. Whereas a 50 to 60 lux light intensity at bird-head height in the breeding period is sufficient to maximise egg numbers, separately-housed males are usually kept at a lower intensity of 20 to 30 lux to control aggressive behaviour.Figure 4. Effect of age at photostimulation on egg production in breeding turkeys

(Lewis and Morris, 2006).

Light colour and lamp type

As is the case for broiler breeders, there is no unequivocal evidence to suggest that the performance of turkey breeders will be improved by using other than white light, that UV light provides any reproductive benefit, or that any particular type of lamp is better than any other. White compact fluorescent lamps currently appear to be the most economic option, but LED lighting is likely to be the selected type in future. It should be noted, however, that supplemental UV may be useful for controlling agonistic behaviour when producing commercial male turkeys.Conclusions

- Turkey breeders exhibit photorefractoriness.

- An initial 3 months of natural light or 14-hour artificial daylengths are necessary to delay photosensitivity

- Provide a two to three month pre-breeding period of short daylengths to dissipate juvenile photorefractoriness. Light-proofing is essential during this phase.

- Abruptly increase daylength to 14 hours at about 24 weeks for males and at about 30 weeks for females to synchronise maturity.

- Maintain 14 hours throughout the laying period in light-tight buildings; longer daylengths will be required where houses are not light-tight.

- Use a light intensity of at least 50 lux in female housing during the laying period to maximise egg production, and 20 to 30 lux to minimise aggression in male housing.

Lewis, P.D. & Morris, T.M. (2006): Poultry Lighting – the theory and practice. (Andover, Northcot).

Lewis, P.D. (2006): A review of lighting for broiler breeders. British Poultry Science 47: 393-404.

Lewis (2009): Photoperiod and control of breeding. in: Hocking, P.M. (Ed) Biology of breeding poultry, pp. 243-260 (Wallingford, CAB International).

Zusammenfassung

Beleuchtungsprogramme für Elterntiere von Masthühnern und PutenWer sich mit der Optimierung von Lichtprogrammen für Mastelterntiere und Puten beschäftigt, sollte zunächst wissen, dass diese – im Gegensatz zu Legelinien – nur bedingt auf Veränderungen der Tageslänge regieren. Wer im Internet-Wörterbuch eine deutsche Übersetzung für ‚photorefractoriness’ sucht, findet ‚keine Ergebnisse’ oder bestenfalls ‚Renitenz’. Gemeint ist die Unfähigkeit, auf Lichtreize zu reagieren, in diesem Fall Auslösung der Geschlechtsreife durch zunehmende Tageslänge.

Broilerelterntiere, die mit kontrollierter Fütterung aufgezogen werden, brauchen länger, um auf zunehmende Tageslänge zu reagieren. Wenn die Fütterung auf 2,0 – 2,1 kg Körpergewicht im Alter von 20 Wochen ausgerichtet ist, reagieren die Tiere erst ab ca. 19 Wochen auf eine Steigerung der Tageslänge. Empfohlen wird eine schnelle Absenkung der Tageslänge während der Aufzucht auf 8 Stunden und eine schnelle Steigerung auf 13 Stunden mit 20 Wochen bei einem Gewicht von 2,0- 2,2 kg. Die Lichtintensität sollte während der Aufzucht höchstens 10 lux, während der Legeperiode mindestens 30 lux betragen.

Elterntiere von Mastputen werden ohne Futterrestriktion aufgezogen. Empfohlen wird eine Beleuchtungsdauer von 14 Stunden während der ersten 3 Monate, danach eine Phase mit kurzer Tageslänge bis zum Beginn der Lichtstimulation. Zur Synchronisation der Geschlechtsreife sollten Puter bereits mit 24 Wochen, Puten erst mit 30 Wochen auf 14 Stunden Licht umgestellt werden. Zur Maximierung der Legeleistung wird für Puten eine Lichtintensität von mindestens 50 lux empfohlen, für Puter dagegen höchstens 20-30 lux zur Minimierung aggressiven Verhaltens