Summary

Bio-energy is used in Europe mainly as a result of government policies. Justifications for government

intervention are the reduction of CO2 emissions and dependency on energy imports. Surplus agricultural

production for many years favoured the governmental promotion of bio-energy. Recent supply shortage

for agricultural products calls for a critical review of past policies of promoting bio-energy. The effect

of increased production and use of bio-energy on the protection of the environment is discussed

critically, keeping food production as first priority in perspective. In the amendment of the EEG, this

requirement has probably been taken into consideration. Against this background, the admixture

quotas for biofuels are critical. In view of the significant rise in food prices, arable land in Europe can

only be used to a limited extent for bio-energy. Additional requirements are covered with the help of

imports. Political decision makers will face increasing pressure from consumers to reduce promotion

of bio-energy to avoid further increase in food prices.

Present information, based on recent price developments, leads us to the conclusion that agricultural food and feed production will have priority over bio-fuel production. For agricultural raw materials the price of fossil fuels is now the lower price limit, while the food market is more competitive. The preferred option for agriculture and rural development is the use of biogenic waste or the double use of agricultural products.

Present information, based on recent price developments, leads us to the conclusion that agricultural food and feed production will have priority over bio-fuel production. For agricultural raw materials the price of fossil fuels is now the lower price limit, while the food market is more competitive. The preferred option for agriculture and rural development is the use of biogenic waste or the double use of agricultural products.

Introduction

Rising crude oil prices, high dependency on imports and in particular the realization that climate change needs to be slowed down by reducing carbon dioxide emissions, are used as arguments for the usage of renewable energies and for the expansion of the use of renewable primary products. This is supposed to reduce the rate of global climate change, at the same time developing new income opportunities for agriculture and forestry. New jobs and the usage of agricultural raw materials for bio-energy production could lead to a stabilization of producer prices and desirable effects on family income in rural areas.2. Promotion by government policy

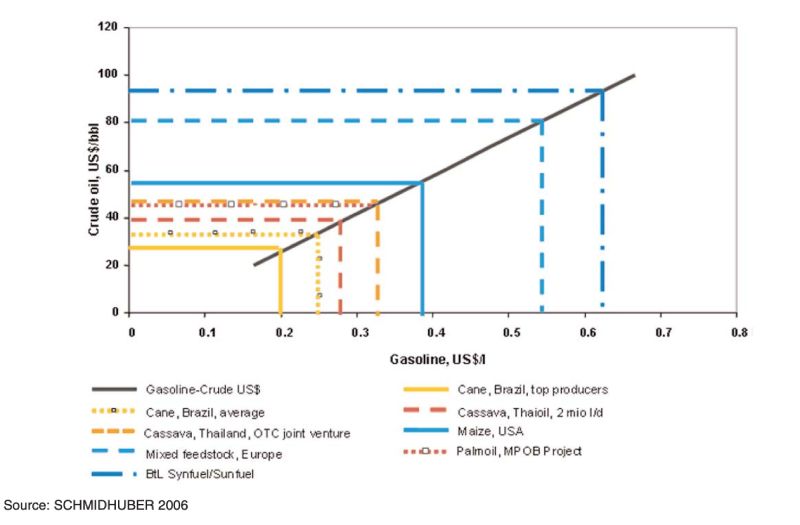

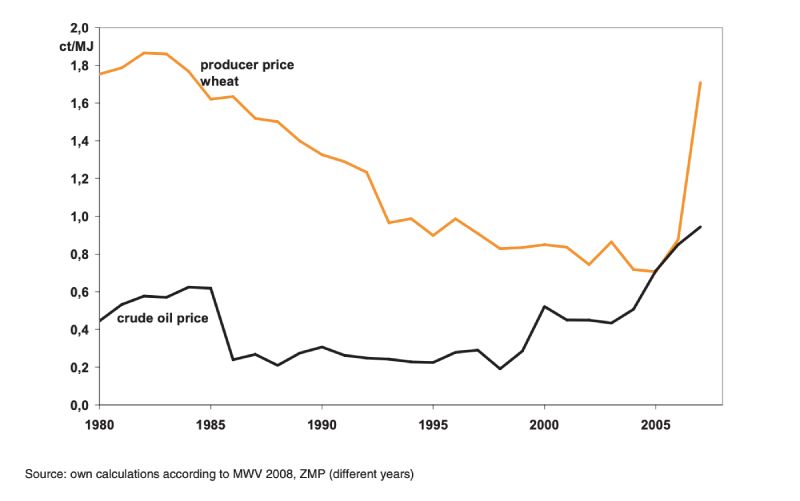

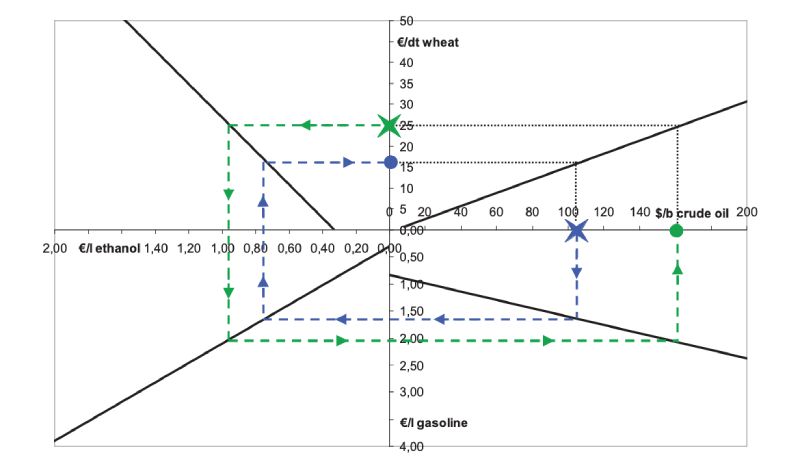

The rising of the crude oil price over the last years aroused the expectation of bio-energy already being competitive. In other countries this is already the case without interventions by the government. The equilibrium conditions specified in Figure 1 indicate at what crude oil price different forms of biofuel are (just) competitive. For the calculations in Figure 1, the price level of agricultural products in 2005 was used. In the meantime, however, prices for agricultural products increased significantly, especially from 2006 to 2007. The competitive conditions may still be the same, but the equilibrium level has shifted upward. This means that bio alcohol is still not competitive in Europe, even at crude oil prices exceeding $ 100 per barrel, because the prices for agricultural products are more than twice as high today than in 2005 (Figure 2). In any case, the use of biofuels only results from market interventions by the government. In the same way, this applies also to some other sources of renewable energy.Figure 1: Parity prices between crude oil, gasoline and biofuels

Figure 2: Price development of crude oil and wheat

The following approaches have been adopted by government policy:

- a) Increase in price of fossil energy

- b) Price reduction of bio-energy

- c) Purchase commitment of bio-energy at a fixed price

- d) Admixture obligation for bio-energy

Concerning a) The price of fossil energy is increasing because of the tax on oil and the eco-tax. The burdens, however, are very different. Gasoline is the most burdened, diesel somewhat less (higher tax for cars with diesel engines), oil is significantly less burdened. Politically it is difficult to achieve equal burdens for all sources of energy.

Concerning b) A price reduction of bio-energy can be achieved either through direct subsidization or through a lower tax burden. Politically the easiest measure probably was to enforce a tax exemption for biofuels. This was first done with biodiesel (from rapeseed oil). Therefore this kind of fuel could be offered at the gas station at a slightly lower price than conventional diesel. The state lost the corresponding revenues from fuel tax, while car owners got the impression that biodiesel is cheaper than diesel.

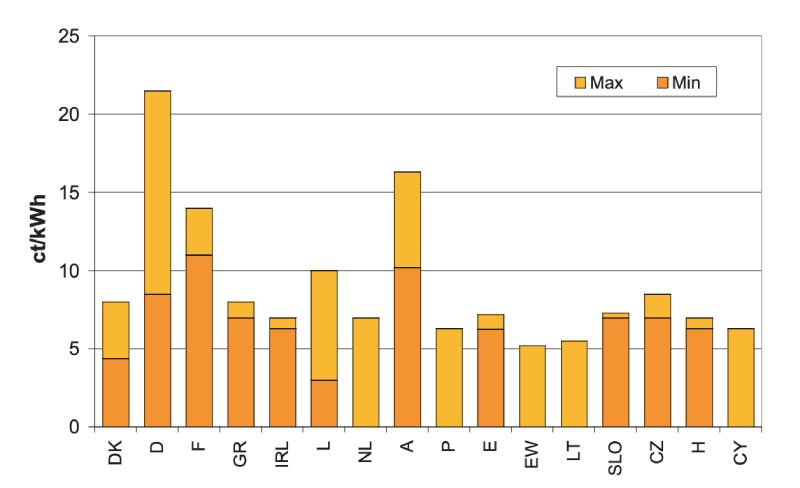

Concerning c) The introduction of a commitment to purchase at a fixed price burdens the consumers of energy instead of the tax payers, who are affected in variant b). This was primarily done for electricity from renewable energy sources. As the share of renewable energy is still relatively small, the consumer does not realize that a very high price has to be paid e.g. for solar energy with about 50 ct/kWh. Concerning agriculture, the determination of the feed-in tariff for electricity from biogas plants was very important, in particular the so-called NawaRo surcharge for agricultural commodities of about 6 ct/kWh in addition to a base salary of about 10 ct/kWh. Moreover, this rate has been guaranteed for a period of 20 years (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Feed-in tariff for biogas in selected countries

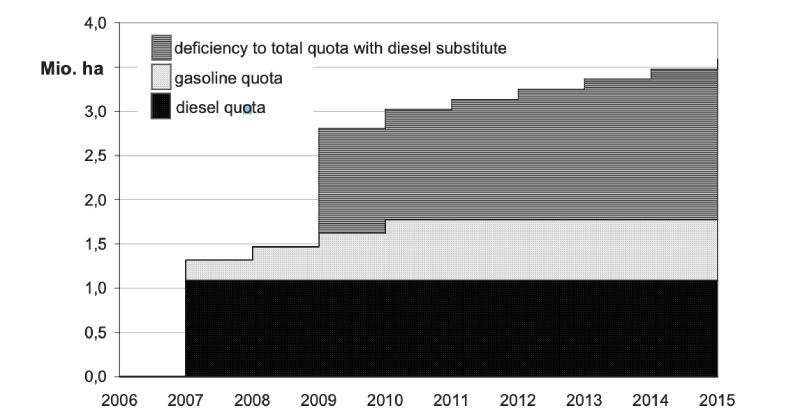

Concerning d) The determination of a specific rate of admixture has recently been carried out for biofuels. Figure 4 shows admixture rates in Germany. As the mineral oil companies are free to decide where to buy the biofuel, the domestic production is no longer in the foreground. Ultimately, the admixture of biofuel can only help to protect the climate to the degree that biofuels burden the climate less than fossil fuels.

Figure 4: Admixture rates

As a preliminary conclusion it can be said that the political interventions helped the renewable energies to achieve a breakthrough. This does not only affect agriculture but also the equipment manufacturers, which do not only supply the domestic market, but also increasingly markets outside Germany.

After a period of broad promotion of renewable energies, it is now necessary to re-examine the policy on subsidies, taking into account all experiences and side effects. It is now clear that not all objectives set concerning the use of bio-energy can be achieved at the same time. Some objectives are conflicting and require prioritization. In Figure 5 selected procedures of bio-energy production are compared. Large differences exist specifically in the energy output per unit of area.

The following issues are discussed controversially today: Is it ensured that bio-energy helps to protect the climate? Are the social costs of the use of bio-energy to reduce carbon dioxide emissions justified? Are consumers willing to accept higher food prices resulting from increased use of biofuel?

3. Selected processes of bio-energy production

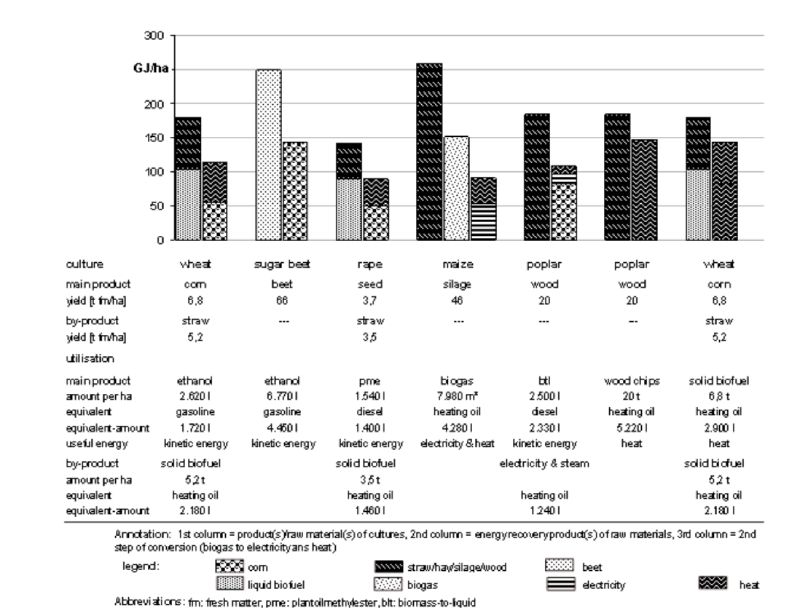

For farms, a series of processes for the production of bio-energy is available. Figure 5 shows the most important indicators of selected procedures. Significant differences exist in the share of usable final energy and in the yield per hectare. Generally the production of biofuels generates consistently a lower yield per hectare than the production of heat, as in the first case a higher implementation loss through the conversion compared to the substitution in the case of heat generation arises. In the production of biofuel animal feed accrue as a by-product. In the case of biogas production, it is crucial to what extent the arising waste heat can be used. A recent variant is to feed the produced biogas into the gas distribution system after processing. This increases the utilisation level of the produced biomass. The processing causes additional costs and can therefore only be operated effectively with larger plants.Figure 5: Primary und final energy content of different cultures

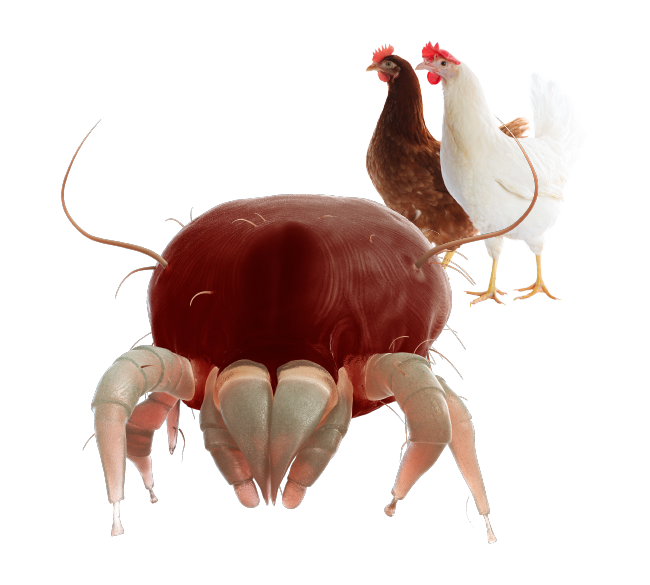

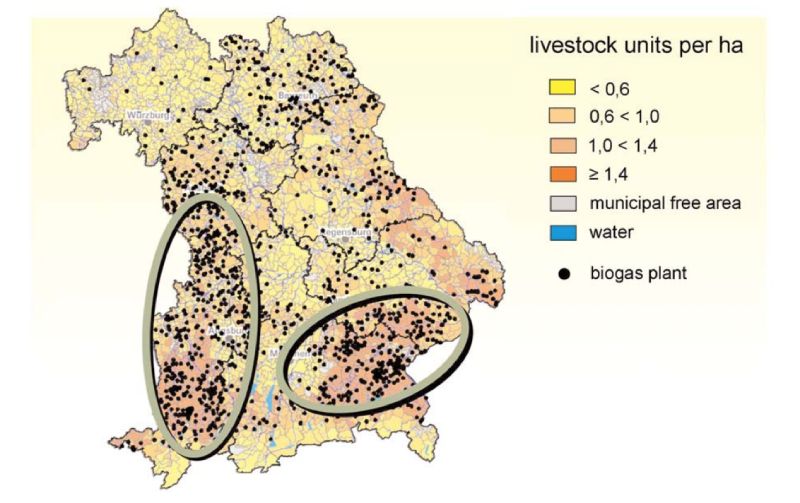

As far as the procedures listed in Figure 5 are concerned, competition between food and energy production is strongest in the domain of biogas production. Since corn silage can be used as feed for cattle and/or for the biogas plant, expansion of biogas production will either require additional acreage for the cultivation of maize silage or a reduction of the cattle population. As shown in Figure 6, we find e.g. in some regions of Bavaria a high density of livestock and at the same time a significant concentration of biogas plants. This competition for land results in rising cost of land lease and biomass, which burden the production cost of bio-energy.

Figure 6: Livestock units und biogas plants in Bavaria (2006)

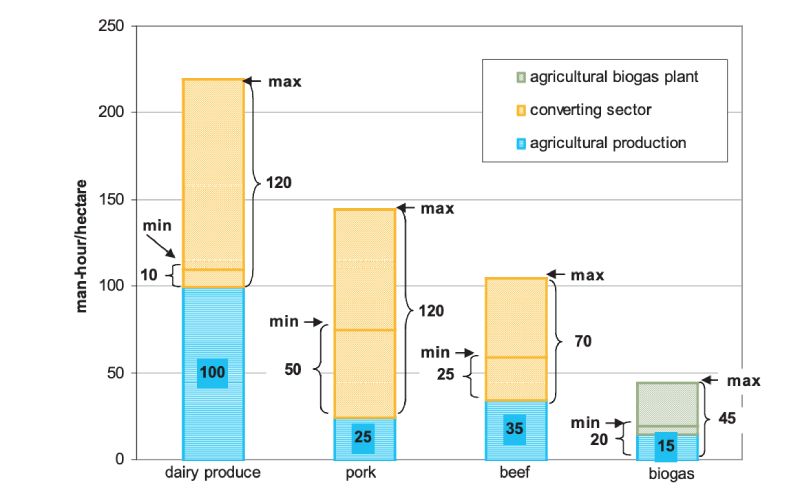

An argument for the extension of bio-energy production is seen in the creation of additional jobs. Figure 7 shows the work hours required for important procedures of animal production on a farm. Furthermore it shows the work hours needed for the processing of agricultural products per unit of area, in the dairy or in the slaughterhouse. It also shows the different sources of biogas. From this comparison follows that the expansion of bio-energy production, represented by the example of biogas, creates additional jobs only if biogas is produced without reducing milk and/or meat production. This is possible if e.g. liquid manure or residual materials are used.

In addition to the biogas production (in Germany 2007 about 0.4 million hectares), the production of biofuels with approximately 1.1 million ha for biodiesel and 0.3 million ha for bioethanol occupies the largest amount of land. From the perspective of the commodity producer the situation has changed significantly in recent years. In 2005, the price of cereals was still about 10 € per 100 kg, currently prices are around 20 € per 100 kg. The cost of bioethanol production has increased correspondingly. As Figure 8 shows, at a crude oil price of almost $ 70 per barrel the price of gasoline (including taxes) is about 1.30 €/l. This kind of gasoline corresponds to a price of bioethanol of just 0.60 € per liter (excluding fuel taxes). The producer of bioethanol could keep the production cost at this level at raw material costs of about 10 €/100 kg for cereals. Currently, the bioethanol producer has to pay about 20 €/100 kg for the raw materials. Under these circumstances, domestically produced bioethanol is not competitive, especially as imported biofuels are significantly cheaper. The economic situation of biofuel producers in Germany is unfavourable, and many plants already shut down.

Figure 7: Working time required per hectare of selected value-added chains of agriculture

Figure 8: Bioethanol from wheat as substitute for gasoline

4. Environmental aspects of bio-energy production

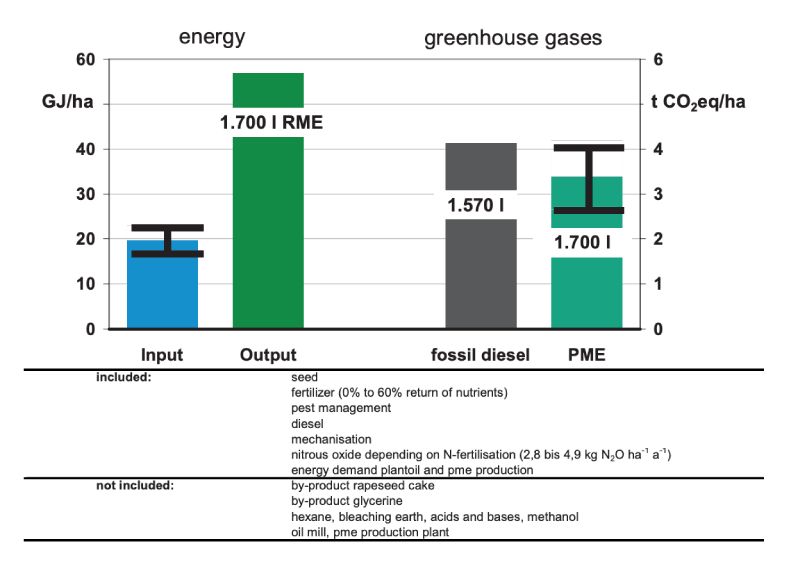

The use of bio-energy is justified with the saving of fossil fuels and with a reduction in the emission of climatically critical gases. Figure 9 shows the energy balance as well as the greenhouse gas balance of biodiesel (PME). Thus, the use of biodiesel instead of fossil fuel leads to a saving of fossil fuel. The main cause is the use of the solar energy stored in the crops. It should be pointed out that with the use of the oil from rapeseed by-products accrue as well, which is in the example of biodiesel the rapeseed cake, which remains after processing the rapeseed. This has to be considered in the balance. A clear assessment of the greenhouse gases is more difficult. In particular, the released amount of nitrous oxide (N2O) varies considerably. Since nitrous oxide is about 300-times more damaging to the environment than carbon dioxide, the cultivation of rapeseed together with a subsequent use of biodiesel can even cause a burden for the climate in comparison to fossil diesel. The procedures of crop production need to be optimized with appropriate attention to nitrous oxide emissions. This applies for the production of renewable raw materials as well as animal feed.Figure 9: Energy balance and greenhouse gas balance of biodiesel (PME)

Calculations for other bio-energy lines (for example, the heat recovery of fast-growing wood) show that for them a more favourable greenhouse gas balance can be achieved. In general, procedures which substitute fossil fuels directly are superior to those procedures which need a chemical conversion. These differences can be seen in the costs of reducing climate-sensitive emissions (CO2 reduction). For heat production, these costs are lower than for the production of biofuel.

BERENZ, S.; HEIßENHUBER, A. (2007): Ökonomische Aspekte zur energetischen Nutzung von Biomasse. Berichte über Landwirtschaft 85 (2), S. 165-177.

BERENZ, S.; HOFFMANN, H. und PAHL, H. (2008): Konkurrenzbeziehungen zwischen der Biogaserzeugung und der tierischen Produktion. In: HEIßENHUBER, A.; KIRNER, L.; PÖCHTRAGER, S.; SALHOFER, K.: Agrar- und Ernährungswirtschaft im Umbruch, Gesellschaft für Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaften des Landbaues e.V., Band 42, Landwirtschaftsverlag Münster-Hiltrup, Weihenstephan.

BGBL. (Bundesgesetzblatt) Teil 1 (2006): Gesetz zur Einführung der Biokraftstoff-quote durch Änderung des BundesImmissionsschutzgesetzes und zur Änderung energie- und stromsteuerrechtlicher Vorschriften (Biokraftstoffquotengesetz -BioKraftQuG) vom 18.12.2006, S. 3180-3188.

BMELV (Bundesministerium für Landwirtschaft, Ernährung und Verbraucherschutz) (Hrsg.) (2006): Statistisches Jahrbuch über Ernährung, Landwirtschaft und Forsten der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 2006. Landwirtschaftsverlag GmbH MünsterHiltrup, Bonn.

BOUWMAN, A. F. (1996): Direct emission of nitrous oxide from agricultural soils. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 46 (1), 53-70.

BOUWMAN, A. F.; BOUMANS, L. J. M.; BATJES, N. H. (2002): Emissions of N2O and NO from fertilized fields: Summary of available measurement data. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 16 (4), 1058.

BVDF (Bundesverband der Deutschen Fleischwarenindustrie) (2007): Umsatz, Beschäftigte und Arbeitsstunden im produzierenden Ernährungsgewerbe 1.

(Abrufdatum: 05.07.2007).

DREIER, T.; TZSCHEUTSCHLER, P. (2000): Ganzheitliche Systemanalyse für die Erzeugung und Anwendung von Biodiesel und Naturdiesel im Verkehrssektor. Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Landwirtschaft und Forsten, Gelbes Heft 72, München.

FNR (Fachagentur für Nachwachsende Rohstoffe e.V.) (Hrsg.) (2005): Leitfaden Bioenergie – Planung, Betrieb und Wirtschaftlichkeit von Bioenergieanlagen. Gülzow.

IGELSPACHER, R. (2003): Ganzheitliche Systemanalyse zur Erzeugung und Anwendung von Bioethanol im Verkehrssektor. Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Landwirtschaft und Forsten, Gelbes Heft 76, München.

KEYMER, U. (2007): Energieerzeugung aus Nachwachsenden Rohstoffen: Ein wirtschaftliches Wagnis? Vortrag zur 16. Jahrestagung des Fachverbandes Biogas e.V. am 01. Februar 2007 in Leipzig. http://www.lfl.bayern.de, http://www.lfl.bayern.de/ilb/technik/16285/index.php (Abrufdatum: 14.2.2007).

KTBL (Kuratorium für Technik und Bauwesen in der Landwirtschaft e.V.) (Hrsg.) (2006): Betriebsplanung Landwirtschaft 2006/07. 20. Auflage, Darmstadt.

LFL (Bayerische Landesanstalt für Landwirtschaft) (Hrsg.) (2003): Leitfaden für die Düngung von Acker- und Grünland. Freising.

MWV (Mineralölwirtschaftsverband e. V.) (2008): Preisstatistiken. http://www.mwv.de/cms (Abrufdatum: 11.02.2008).

RAUH, S. und HEIßENHUBER, A. (2008): Flächenkonkurrenz der Nahrungsmittel- und Energieproduktion um Biomasse anhand des Beispiels Bayern. In: KOPETZ, H.; EBERL, W.; FERCHER, E.: Mitteleuropäische Biomassekonferenz 2008, Österreichischer Biomasse-Verband, Graz, S. 112.

RÖHLING, I.; KEYMER, U. (2007): Biogasanlagen in Bayern 2006 – Ergebnisse einer Umfrage. Bayerische Landesanstalt für Landwirtschaft (LfL), Freising-Weihenstephan.

SCHMIDHUBER, J. (2006): Impact of an increased biomass use on agricultural markets, prices and food security: A longerterm perspective. International Symposium of Notre Europe, 27.-29. 11. 2006, Paris.

THRÄN, D.; WEBER, M.; SCHEUERMANN, A.; FRÖHLICH, N.; ZEDDIES, J.; HENZE, A.; THOROE, C.; SCHWEINLE, J.; FRITSCHE, U.; JENSEIT, W.; RAUSCH, L. und SCHMIDT, K. (2005): Nachhaltige Biomassenutzungsstrategien im europäischen Kontext. Institut für Energetik und Umwelt (IE), Leipzig.

WEINDLMEIER, J. (2006): Arbeitszeitaufwand für Milcherfassung und -verarbeitung in Molkereien. Leiter der Professur für Betriebswirtschaftslehre der Milch- und Ernährungsindustrie in Weihenstephan, persönliche Mitteilung, 07.11.2006

ZMP (Zentrale Markt- und Preisberichtstelle GmbH) (Hrsg.) (versch. Jahrgänge): ZMP Marktbilanz; Getreide Ölsaaten Futtermittel; Deutschland Europäische Union Weltmarkt. Bonn.

Zusammenfassung

Bioenergieproduktion aus ökonomischer und ökologischer SichtDer Hauptgrund für die Produktion und Nutzung von Bioenergie in Europa ist eine steuerliche Begünstigung, um CO2 Emissionen und die Abhängigkeit von Energieimporten zu verringern. Solange die Landwirtschaft mit Überschussproduktion und entsprechend niedrigen Erzeugerpreisen zu kämpfen hatte, war die Erzeugung von Bioenergie eine plausible Alternative. Inzwischen hat sich jedoch das Verhältnis von Angebot zu Nachfrage derart verschoben, dass es an der Zeit ist, die politische Unterstützung der Bioenergie einer kritischen Prüfung zu unterziehen.

Wenn man die Sicherung der Lebensmittelversorgung als oberste Priorität gelten lässt, muss man sich fragen, was der Einsatz von Bioenergie zum Umweltschutz beitragen kann. In der Novellierung des EEG dürfte diese Forderung bereits Berücksichtigung finden. Vor diesem Hintergrund werden auch die Beimischungsquoten für Biokraftstoffe kritisch gesehen. Angesichts erheblich gestiegener Erzeugerpreise für Lebensmittel und Tierfutter kann nur ein kleiner Teil der landwirtschaftlichen Nutzfläche für die Produktion von Bioenergie genutzt werden. Der weitere Bedarf muss aus Importen gedeckt werden. Politisch wird der Druck steigen, die Förderung der Bioenergie zurückzunehmen, um einen Preisanstieg nicht zusätzlich zu forcieren.

Unsere Schlussfolgerung aus der jüngsten Preisentwicklung ist, dass die Produktion von Lebensmitteln und Futter für die tierische Veredelung vorrangig gegenüber Bioenergie sein wird. Bei den agrarischen Rohstoffen gibt jetzt der Preis der fossilen Energieträger die Preisuntergrenze vor. Die höhere Wettbewerbskraft liegt aber beim Nahrungsmarkt. Für die Landwirtschaft und den ländlichen Raum besteht vor allem die Chance der Nutzung von biogenen Reststoffen bzw. in der Doppelnutzung von agrarischen Rohstoffen.