The results come from a collaborative project between the University of Edingburgh, University of Glasgow, Aviagen Ltd and LOHMANN TIERZUCHT GmbH.Each year the poultry industry needs to supply huge numbers of chicks that will grow to become egg-laying and meat-producing chickens. This is possible because we can artificially incubate eggs and hatch chicks – because the breeding hens do not need to incubate their eggs, each one can produce many more eggs and chicks. Artificial incubation also reduces the chance that diseases will be transmitted from mother to chick. The transmission of disease between generations can still occur, especially during the collection and transport of eggs. If eggs are infected with micro-organisms that are harmful to the egg contents this is bad for food safety, and animal and human health, so anything that can reduce this will help maintain biosecurity and reduce the risk further for the consumer.

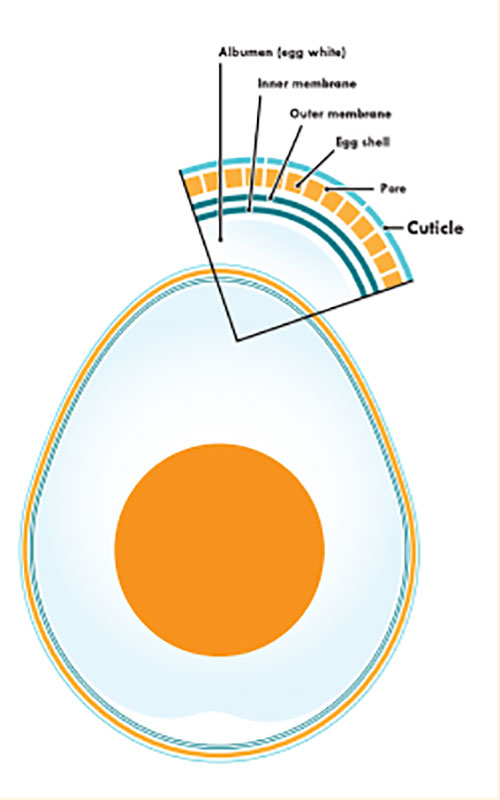

The cuticle

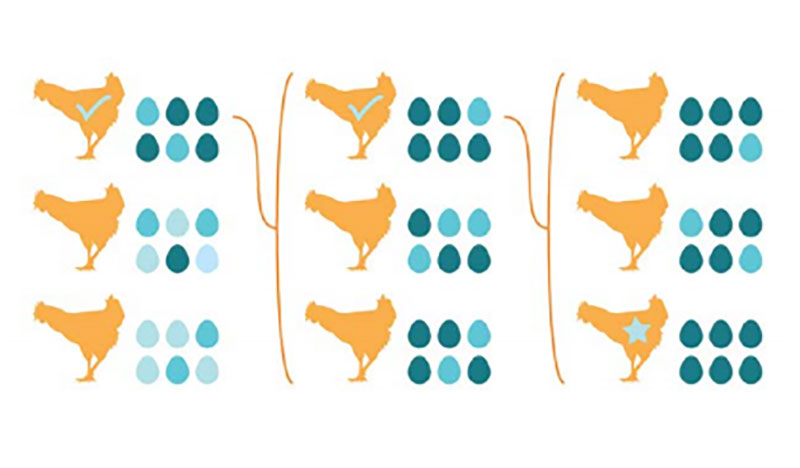

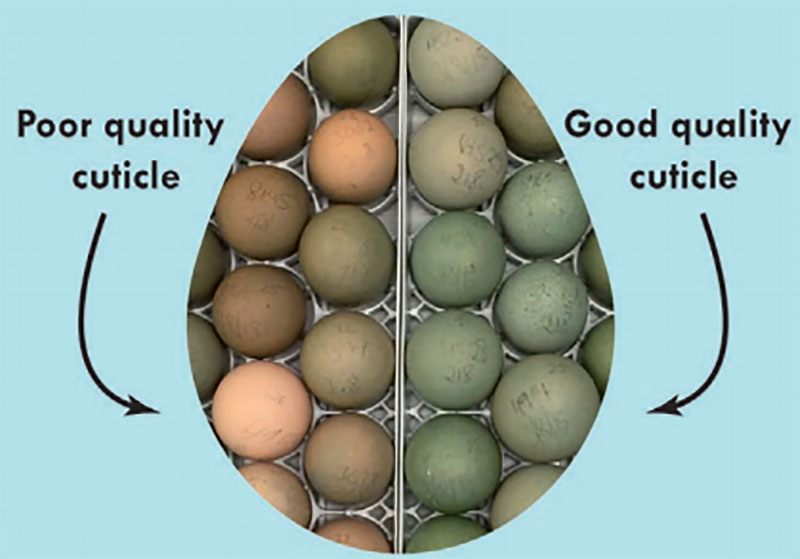

The cuticle is a protein layer which covers the surface of the egg and fills the pores in the shell which allow air inside for the growing chick. The cuticle is the egg’s first line of defence against bacteria that could come from the mother as the egg is laid and from the environment e.g. from contact with egg collecting belts or handling equipment. Not all eggs have cuticles of the same quality – natural variation between hens means that some cuticles are better than others. This variation in cuticle quality means that some eggs are more vulnerable to invasion by bacteria and studies have shown that eggs with good quality cuticles are almost never infected with E. coli whereas eggs with poor quality cuticles were infected more often. If we can select for better cuticle quality, this will reduce the contamination of eggs by E. coli and other potentially harmful micro-organisms.We have developed ways to measure the amount of cuticle individual hens deposit on their eggs and link that to information about the hen’s genetics, some of which we obtain by sequencing their DNA. This combination of genetic information and cuticle quality data will allow us to accurately select or breed hens that lay eggs with high quality cuticles that are better protected against bacteria. We have also learned a lot more about how the cuticle is made, just as the egg is laid, and how other factors such as the bird’s environment, stress, hormone levels and the age of the hen and the egg affect cuticle quality.

How do we measure cuticle quality?

We work with chemists at the University of Edinburgh to develop light-based techniques to measure cuticle quality. White light is made up of a spectrum of many different wavelengths of light and all materials, including the egg’s cuticle, absorb and reflect light from different parts of this spectrum. We can use a machine called a spectrophotometer to measure the amount of light reflected at any given wavelength from different eggs and compare them, to get a measure of cuticle quality. We also use techniques such as fluorescence lifetimes, steady state fluorescence

and infrared spectroscopy to tell us more

about cuticle quality and the chemical

structures involved. Some of our methods

involve staining the eggs to reveal more

about their cuticle (as in the Cute Egg: Staining activity in our Cute Egg kit), and we

are also investigating the many different

proteins that make up the cuticle.

We also use techniques such as fluorescence lifetimes, steady state fluorescence

and infrared spectroscopy to tell us more

about cuticle quality and the chemical

structures involved. Some of our methods

involve staining the eggs to reveal more

about their cuticle (as in the Cute Egg: Staining activity in our Cute Egg kit), and we

are also investigating the many different

proteins that make up the cuticle.Our other partners

Scientists at the University of Glasgow measure thousands of eggs each week which we can combine with the genetic information we have for each egg and bird in the study. They also study the bacteria in eggs with very good and very poor cuticles to find out how cuticle quality affects invasion by bacteria. We also work with industrial partners, who provide us with egg samples and genetic information, sharing with us both their sample resources and their knowledge. They help us decide how to design our custom instrumentation so that it is useful for measuring cuticle quality in the real world, and they will field test the final product for us. For more information visit www.roslin.ed.ac.uk/CuteEggNicola Stock, Roslin Institute and Royal School of Veterinary Studies, University of Edingburgh