In recent years, the social behavior and welfare of laying hens has gained more importance in laying hen breeding programs. Damaging behavior such as feather pecking is of particular concern. Addressing this welfare issue has attracted more attention than ever before and is likely to become even more challenging with the prospect of a ban on beak treatment in many countries in the future.

Three different levels of pecking behavior

Feather pecking is affected by many different factors, so a multifactorial approach attending to different parameters should be taken to minimize its negative impact. This undesirable behavior can occur in every housing system; however, it is especially relevant and more variable in alternative cage-free housing systems due to the bigger group sizes and more complex environment. The literature describes three different levels of pecking behavior: gentle feather pecking, which does not result in the removal of a feather; severe feather pecking, which leads to feather losses at the back, rump or tail of the victim; and aggressive pecking, which is the most serious type of feather pecking and is usually directed at the head. One of the strategies for minimizing the problem is to select against this bad behavior. Directly observing and evaluating an individual bird in a group automatically is a technical challenge and is extremely time-consuming to perform manually.

Ban on beak treatment

Although beak treatment has proven to be a very effective preventive measure for avoiding feather pecking, there is a growing ethical controversy in which this practice is regarded as amputation. Some countries have banned this practice completely and others are set to join this initiative soon. The ban on beak treatment is a new driving force behind the search for solutions to reduce the incidence of feather pecking. Whether and to what extent genetic selection can contribute to this goal will be illustrated by the results of hen-specific measurements on the shape length of pure line layers.

Measurement of beak length

Several years ago, a special device was developed to generate precise data relating to the length of the hen’s beak, in order to evaluate the feasibility of using it as an additional selection criterion. The idea behind it is as follows: if no beak treatment is carried out in the future, birds with blunt beaks will reduce the damage inflicted on their fellows if they start pecking. With the aid of this equipment, the difference in length between the upper and lower beak (referred to as “beak length” below for simplicity) is measured and automatically saved to a database (figure 1).

Figure 1: Automatic measurement of beak length

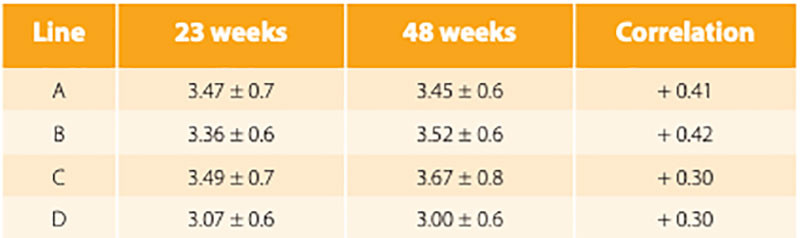

As can be seen in table 1, there is no very clear trend in average beak length at different ages for different brown egg lines. However, it seems that the growth of beak tissue compensates for or even exceeds the abrasion in single hen cages. The phenotypic correlations between measurements at 23 and 48 weeks of age indicate an acceptable repeatability of the measurement at different ages.

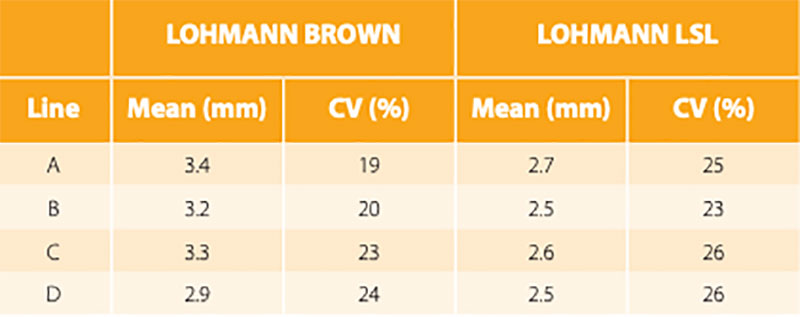

A comparison between the different lines of the LOHMANN BROWN and LOHMANN LSL breeding program is shown in table 2. The average values for beak length are based on around 3,000 individual hens in each line. The measurements were captured at 30 weeks of age.

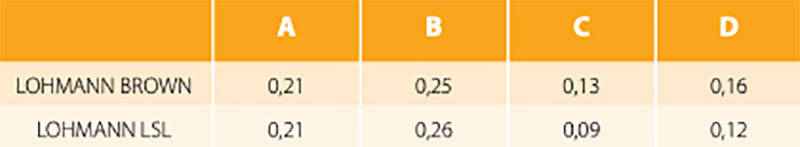

As can be seen in table 3, the heritability estimates for beak length are at a moderate level, with h² ranging from 0.09 to 0.26 for the four lines of the LOHMANN BROWN and LSL breeding program. In light of the genetic parameters and the high variability found in the trait, breeding to reduce beak length through genetic selection is feasible. These heritabilities are at the same level as other selecteda traits such as plumage condition or egg number at the end of production (persistency).

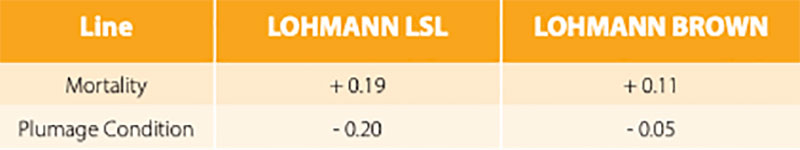

As mentioned above, for the past 20- plus years LOHMANN layers have not only been scored for beak length but also for their plumage condition. Therefore, full-sibs and crossbred half-sibs with pedigree information are housed in group cages, both on breeding farms as well as on commercial farms under field conditions.In the field test, these layers are scored for their plumage condition at around 40 and 75 weeks of age. Families that show intact plumage are scored with the value 9, whereas families with damaged feathering are downgraded due to the amount of feather loss. Based on this information, genetic correlations between beak length and plumage condition and mortality were estimated. As can be seen in table 4, there is a positive correlation between mortality and beak length and a negative correlation between beak length and plumage condition. Birds with shorter beaks have lower mortality and better plumage condition

We conclude from our data that individual selection for blunt beaks, with a reduced difference in length between the upper and lower beak, will help to accelerate the reduction of feather pecking and cannibalism, while family selection for intact feather cover and liveability is continuing and management practices will be optimized.

Dr. Matthias Schmutz

Table 1. Average values ± standard deviation for beak length (mm) at 23 and 48 weeks of age and their phenotypic correlation for the four lines of LOHMANN BROWN

Table 2: Average values and variation coefficient for the beak length of different lines of LOHMANN BROWN and LOHMANN LSL origin

Table 3: Heritability of beak length

Table 4: Genetic correlations between beak length and plumage condition and mortality