Abstract

Outbreaks of Avian Influenza (AI) in the USA from 2014 onwards affected 42.1 million layers and pullets as well as 7.5 million turkeys. From a special analysis of the outbreaks it becomes obvious that migrating birds played an important role in spreading the disease throughout Northern America. Depopulation, transport and deposition of the dead birds from large farms caused major problems.

There existed no adequate experience and facilities to handle these large amounts of infectious material, e.g. birds and manure. The dimension of the AI outbreaks raised again the discussion on vaccination. The advantages and disadvantages are discussed in detail. An emergency fund was installed by the US government to compensate the farmers for the value of the birds killed by the disease and the stamping out measures. This compensation, however, does not comprise the economic losses through the interruption of the production chain. The shortage of table eggs lead to a sharp increase in egg prices in the USA. Imports of processing eggs from Europe had also an impact on the egg prices in Europe. It is expected that the affected poultry farmers in the USA will need about one year to recover. Farmers as well as government authorities are preparing strategies to cope with future outbreaks of AI.

Keywords

Avian Influenza, laying hens, turkeys, broilers, pullets, economicsAvian Influenza, laying hens, turkeys, broilers, pullets, economics

Introduction

The Avian Influenza outbreaks in the USA between December 2014 and June 2015 are the most severe epizootic event in the history of the poultry industry in this country. There had been outbreaks of the HPAI H5N2 strain of the virus in Pennsylvania in 1983/84 and of the LPAI H7N2 strain in Virginia in 2002, but these outbreaks were comparatively small, although in Pennsylvania about 17 million birds were affected. The recent outbreaks affected almost 42.1 million table egg laying hens and pullets and 7.5 million turkeys.

The main goals of this status report are:

- to present a time-spatial analysis of the outbreaks,

- to discuss the epidemiology of the outbreaks,

- to give an overview on the economic impacts of the outbreaks,

- to present scenarios regarding the possibility of future outbreaks.

The following analysis is based on reports of the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), reports and personal information from the state veterinarians of Iowa, North Dakota and Montana, personal information from Prof. Hongwei Xin (Iowa State University, Ames), Jonathan Cade (president Hy-Line) and Dr. Simon Shane (Chick-Site.com) and various reports in

WATTAgNet.com.

A time-spatial analysis of the AI outbreaks

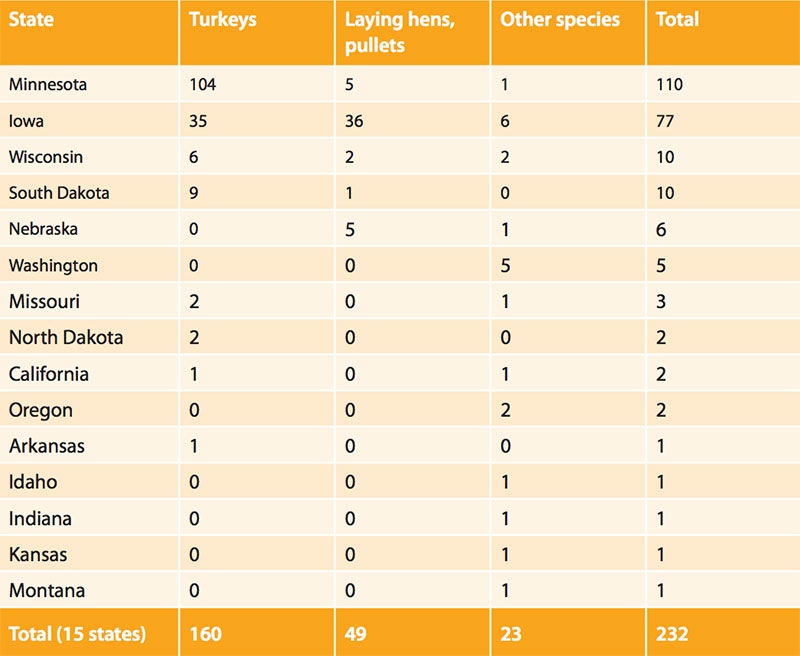

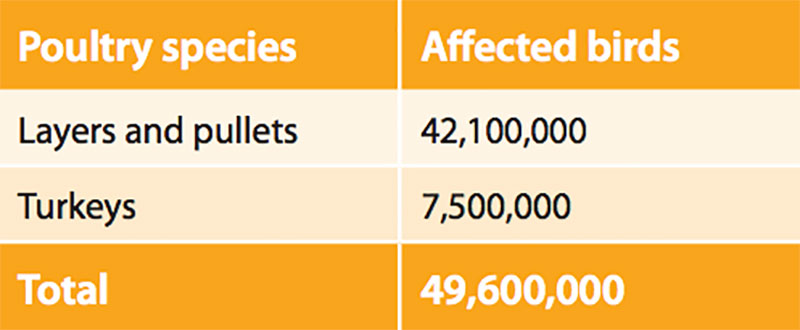

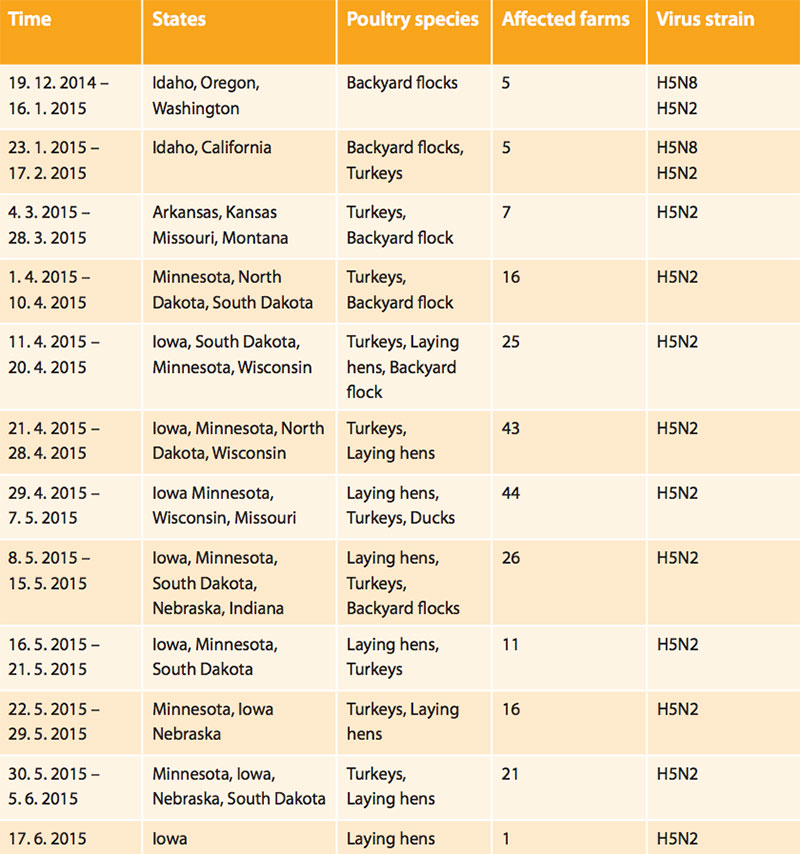

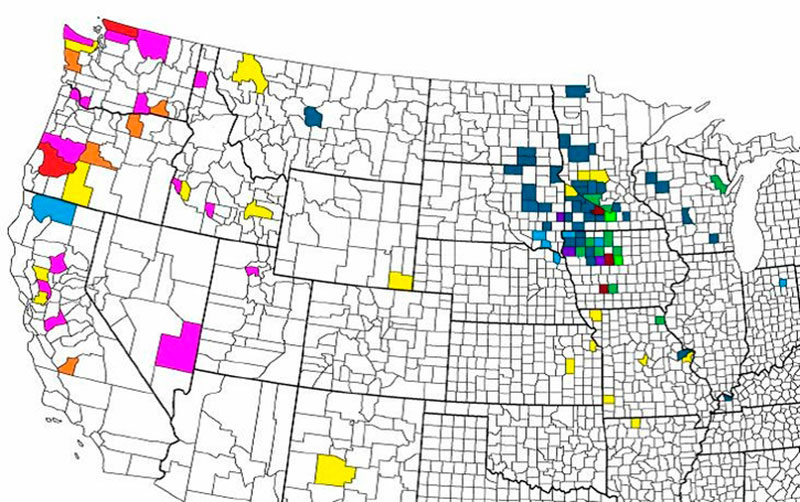

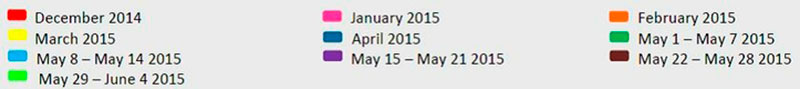

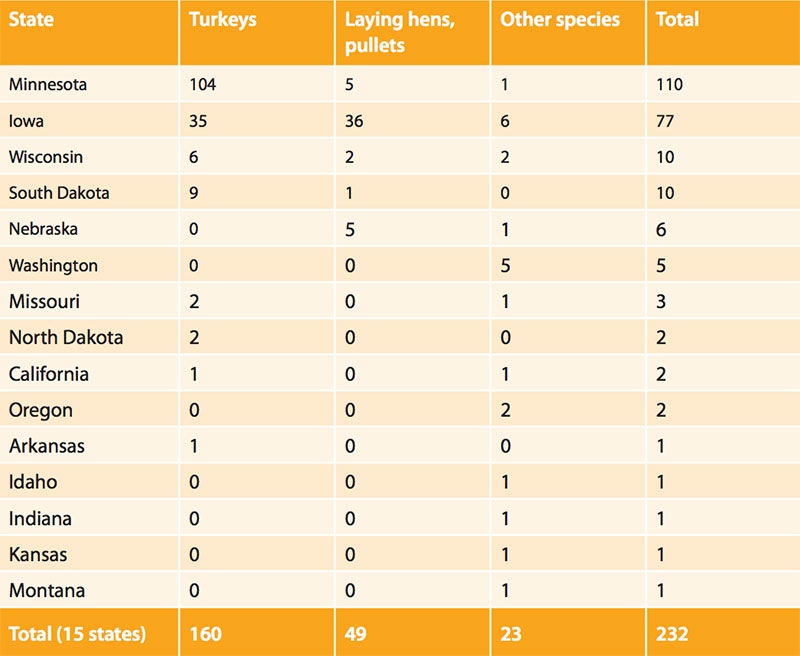

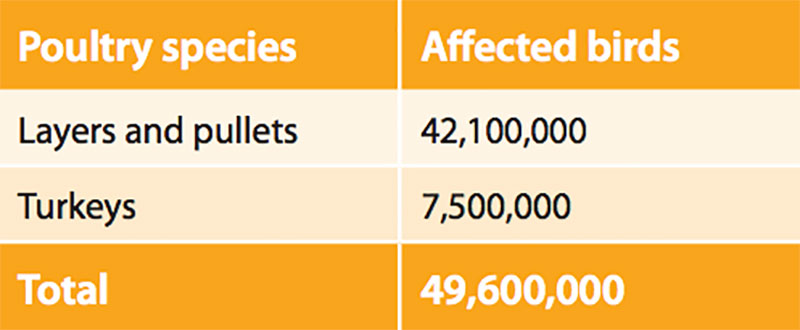

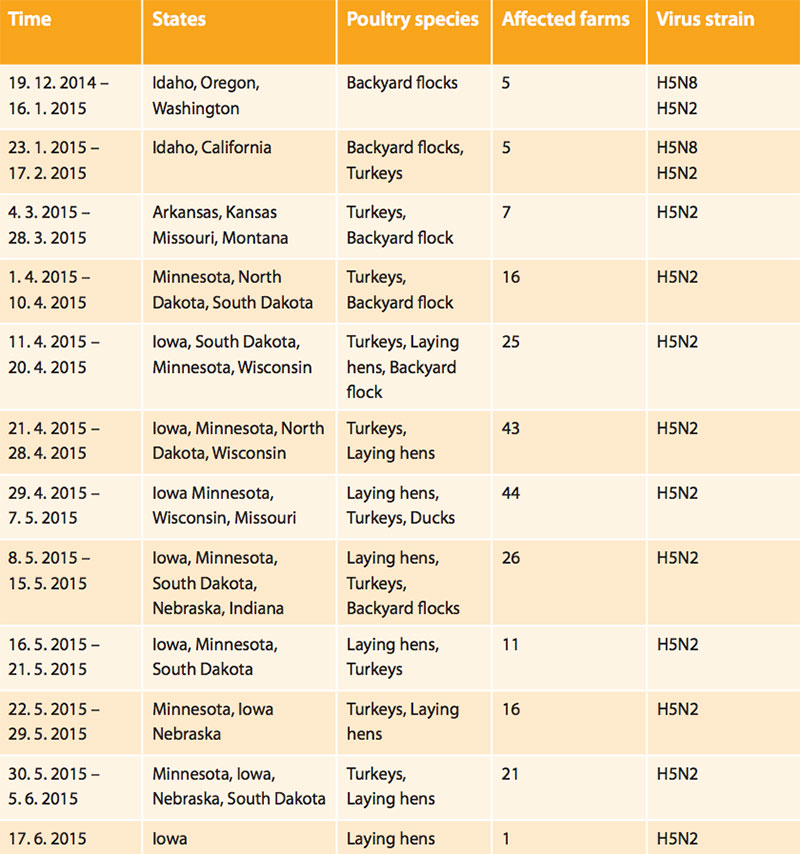

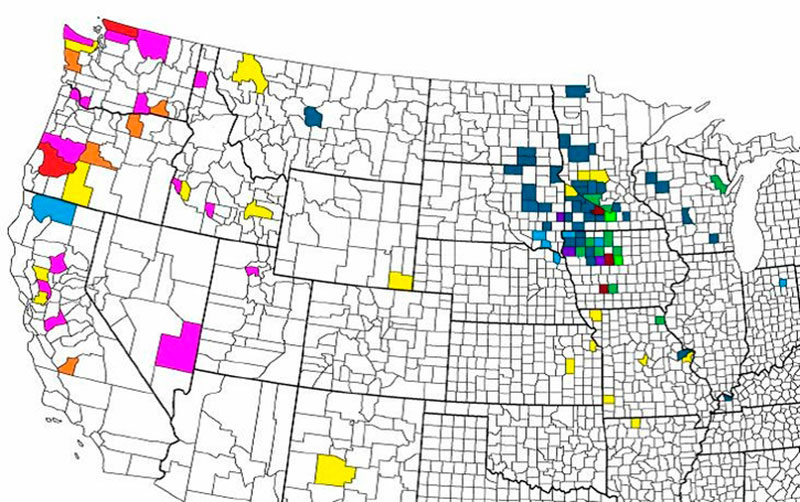

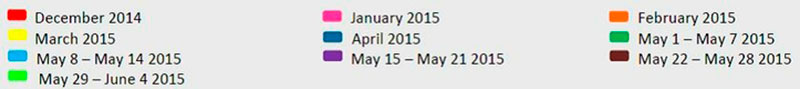

Between December 19th, 2014 and June 17th, 2015 232 outbreaks (commercial poultry and backyard flocks) occurred in 15 states of the USA, 187 in Minnesota and Iowa alone (table 1). In total 42.1 million laying hens and pullets as well as 7.55 million turkeys were affected (table 2, figure 1). From the data in table 3, figure 2 one can easily see that only a few cases were documented by APHIS in December 2014 and January and February 2015. The virus strains which were identified were H5N8 and H5N2.

Table 1. AI outbreaks in the USA until June 17th, 2015

(Source: Author, based on APHIS data)

Table 2. Number of birds affected by the AI outbreaks (status: June 18th, 2015) (Source: Author, based on APHIS internal report data)

Table 3. Time-spatial dissemination of the AI outbreaks in the USA between December 19th, 2014 and June 17th, 2015

(Source: Author, based on APHIS data)

The commercial turkey farms in California were infected by wild birds migrating in the so-called Pacific flyway. The first cases outside this region were detected in Arkansas, Kansas and Missouri between March 3rd and 28th, 2015. As only single farms were affected, the situation did not seem to be alarming. The situation became critical, however, in early April when 16 new outbreaks were confirmed in Minnesota and in the Dakotas, mainly in commercial turkey farms. In the following weeks, the number of infected farms increased dramatically and reached 87 outbreaks between April 21st and May 5th. In addition to turkey farms, the first large laying hen farms were infected in Iowa. In the following weeks, the number of outbreaks decreased but reached a new peak in late May and early June. After several days of no new outbreaks, a last case was confirmed by APHIS in a large layer farm in Iowa on June 17th.

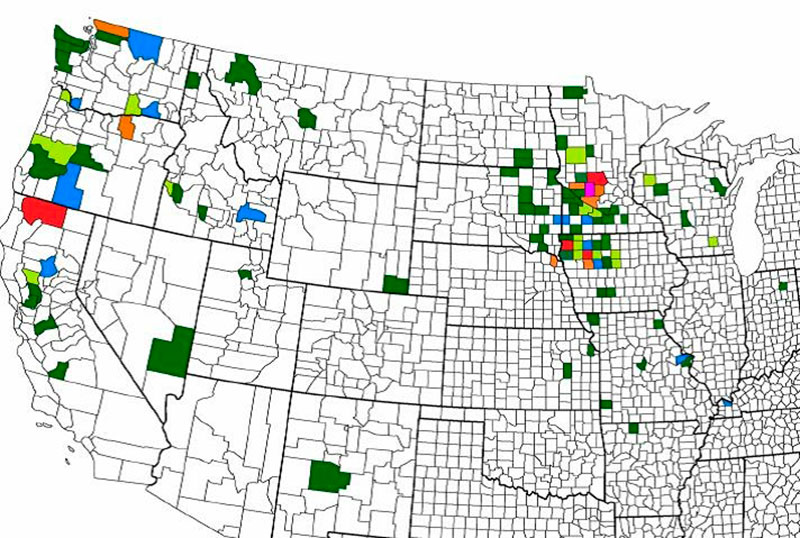

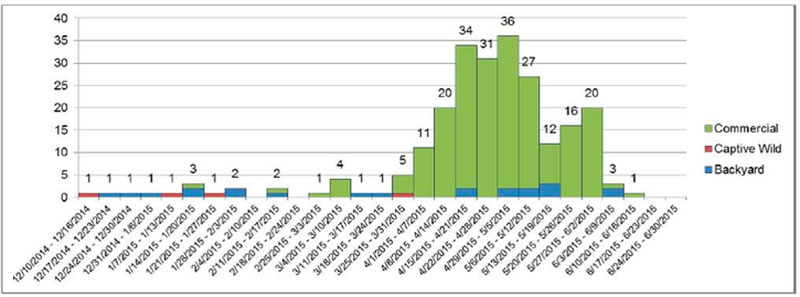

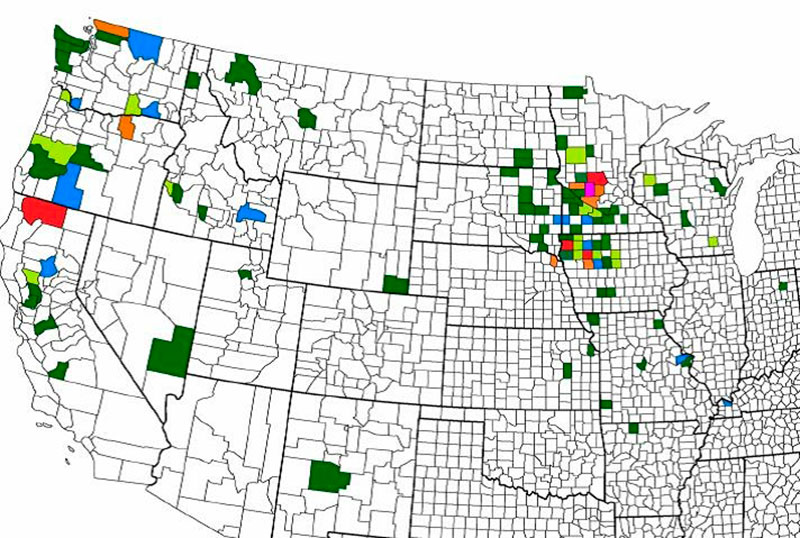

The history and distribution of AI outbreaks are shown in figures 1 – 3.

Figure 1. Spatial distribution of the outbreaks. While in the states at the Pacific Rim only two commercial flocks were detected in California, the outbreaks in the upper Midwest were clustered in southern Minnesota (mainly turkey farms) and in northern Iowa (turkey and table egg layer farms).

(Source: USDA APHIS)

Figure 2. Early outbreaks in the western USA occurred between December 2014 and March 2015 (see also table 3). In March, the first cases were detected in several states which are located in the so-called Mississippi flyway (Minnesota to Arkansas). Beginning in April 2015, the number of detected infections increased rapidly, first mainly in turkey farms, later also in table egg layer farms and the virus disseminated southward and westward (see also table 3).

(Source: USDA APHIS)

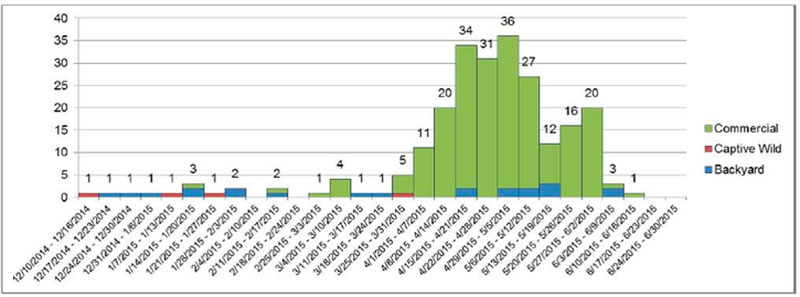

Figure 3. Sequence of the outbreaks in form of an epidemiological curve between December 10th, 2014 and June 2nd, 2015. It is obvious that within this time span, the infection through wild birds changed to infections by virus transmission through personal contacts or through vehicles and equipment. There is no final report available regarding the sudden end of the outbreaks. Higher temperatures, the reduced number of birds that could be infected or a better biosecurity on farm level may have been the main factors.

(Source: USDA APHIS)

The epidemiology of the outbreaks

Dr. David Swayne, Laboratory Director Southeast Poultry Research Laboratory, Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Athens, Georgia, presented a paper on the Risk of Introducing Avian Influenza through Trade in Live Poultry and Poultry Products at the International Conference on Avian Influenza and Poultry Trade which was held by APHIS in Baltimore (Maryland) from June 22nd to 24th. He informed the participants of the conference that his center had analysed viral isolates from all outbreaks. This made it possible to decide if an infection came directly from a wild bird or was transmitted from one infected farm to another. While the first outbreaks obviously came from infected wild birds, the clusters of farms with identical isolates made it likely that the virus had been transmitted either by persons, vehicles or equipment

(figure 3). The latter finding indicated that a lack of biosecurity measures added to the rapid dissemination of the virus and the high number of outbreaks in one county or between farms of a single company as was the case in Iowa and Nebraska.

The influenza virus which led to the severe epizootic event in the states of the upper Midwest and the northern Great Plains was introduced into North America from Asia in the last months of 2014 by wild birds. This strain reassorted obviously into H5N1 and H5N2 viruses. As Dr. Swayne explained, these strains have a combination of genetic material from the highly pathogenic Asian virus and the low-pathogenic North American viruses. These viruses, especially H5N2, caused the infections. Although the viruses are highly pathogenic to commercial poultry, they do not kill the waterfowl. But the wild birds can shed a lot of virus and were the source for the first infections of domestic poultry flocks, in particular turkey flocks.

One question remains, however:

Will the wild birds on their way back from the brooding areas in Canada to warmer regions of the USA still carry the same virus or will that perhaps have mutated into another strain. It will be also decisive for the future of AI infections if the wild birds use the same flyways as in spring and early summer of 2015 or if they also use the eastern or Atlantic flyway which will then also be a threat for the broiler farms in the Mid-Atlantic states and the Southeast where over 90 % of the US broilers are raised.

Depopulation and deposition problems

The first AI outbreaks in turkey farms in Minnesota affected relatively small flocks. The euthanisation and depopulation did not cause serious problems. The birds were killed by water based foam and then composted in the barns. The situation changed completely when large layer farms in Iowa and Nebraska with millions of birds were infected. High-rise barns with up to 12 tiers were a challenge. It would have been possible to kill the birds with CO2 gas, but then the depopulation of barn complexes with up to 1 million birds could not be completed within a few days so that serious hygiene-problems had to be expected. Therefore it was decided that mobile modified atmosphere killing

(MAK) carts using CO2 would be used which could handle up to 100,000 birds per day. Even the use of several MAK Carts at one farm would need up to two weeks to depopulate a farm. In the meantime the virus further spread and the high mortality rate also caused hygiene-problems.

According to a report from APHIS, the depopulation of all affected farms was completed in the first week of July. As the laying hens and pullets could not be composted inside the barns, other ways had to be found to get rid of them. As no privately-owned rendering plants accepted the poultry carcasses, it was decided to deposit them in large landfills. After days of negotiations, several landfills in Iowa accepted the deposition of the dead birds. The problem, however, was that they were about 200 miles away from the clusters of infected farms. It was therefore necessary to store the carcasses in sealed biobins and to use trucks with special equipment to avoid a further dissemination of the virus along the transportation routes. A note from a landfill in southwestern Iowa

(Mills County) from Friday, June 26th, to no longer accept dead birds shows, however, that the problem was still existing in late June. The owners of the landfill also declared that they were not sure if they would accept euthanised birds in another outbreak of AI in future. An alternative way to dispose of the carcasses, might have been to bury or to incinerate them. These alternatives were, however, not applied in large scale. In August 2015, APHIS published a draft on possible impacts of “Carcass Management During a Mass Animal Health Emergency” in which future regulations are proposed and discussed to avoid negative impacts on the environment.

Another problem was the management of the manure from infected farms. Untreated manure, if used as a fertiliser, can be one factor in the dissemination of the AI virus. This is especially the case when the manure is transported to fields of other farms or even into another county at a point of time when the herd does not show clinical signs of an infection. This may have been the case because of the relatively long time (up to 8 days) from a first infection to obvious clinical signs.

Vaccination or not

The dimension of the outbreaks and the resulting economic impacts raised the question if in addition to the stamping out of the infected flocks vaccination of the not infected herds should be permitted.

The main arguments of the poultry farmers in favour of a vaccination were:

- The stamping out method is not adequate to control the further dissemination of the highly pathogenic AI virus,

- the affected areas are too wide spread to prevent a further dissemination of the virus,

- vaccination is necessary to protect valuable flocks, especially breeding stock.

The main arguments brought forward by scientists and representatives from USDA APHIS and some state veterinarians were:

- vaccination does not prevent an infection of flocks and creates clinically silent virus shedders,

- it is difficult to differentiate between infected an non-infected birds in vaccinated flocks,

- vaccination of all flocks in the affected states will result in high costs,

- vaccination will lead to further trade restrictions.

After intensive negotiations between poultry farmers and APHIS, the USDA decided on June 3rd not to permit vaccination. It argued that there were no convincing results regarding the efficacy and the availability of the suggested vaccine. It was also argued that a vaccination would have far reaching impacts on the foreign trade with poultry products, especially broiler meat (see Egg-Cite newsletter, June 5th, 2015).

A new discussion regarding vaccination started in late July 2015. The USDA announced that in case of a new massive AI outbreak in fall 2015 or spring 2016 vaccination might be an alternative in addition to the stamping out of flocks to avoid an uncontrollable dissemination of the virus. Sara McReynolds, Assistant State Veterinarian in North Dakota, in a meeting in Bismarck with the author (July 28th, 2015) declared that vaccination should only be applied if all other means of stopping the dissemination of the virus were not successful. However, she also stated, that it was becoming more and more difficult to explain to the public that birds which were not affected and did not show any clinical signs of the disease should be killed to prevent a further spread of the virus (preemptive slaughter).

In late August, APHIS was expected to issue a request for proposal to manufacturing producing companies to produce avian influenza vaccine to protect poultry flocks from future outbreaks of the highly pathogenic H5N2 virus. The vaccine would be kept on hand in the National Veterinary Stockpile. It would only be used at a situation when it seemed necessary to eradicate the virus. This announcement was severely criticized by industry representatives regarding the efficacy and possible impacts on trade with poultry products (WATTAgNet, August 18th, 2015).

Economic impacts

In an internal report, dated July 3rd, 2015, the USDA informed about the economic impacts and the direct costs of the AI outbreaks. According to this report, the depopulated farms represented 7.5 % of the average turkey inventory of the USA or 3.2 % of the annual turkey production of 240 million turkeys. The losses caused by the depopulation of the affected layer farms were higher; they represented 10.1 % of the average layer inventory and 6.3 % of the pullet inventory. Direct impacts on broiler production were negligible as only 0.01 % of the average broiler inventory was affected.

To compensate the poultry farmers for the direct losses, the US government installed an emergency fund of $ 93.4 million. It very soon became obvious that the fund would not be able to cover the direct losses of the affected farms. So it had to be raised twice to a total of $ 698 million. The compensation was paid on the basis of the value of the birds at the day of the confirmation of the infection ($ 621 million by mid-August). No compensation was paid for the economic losses resulting from the inability to produce because of the standstill after the depopulation of the farms.

In total, 3,440 persons from state and federal agencies and contractors (for example depopulation crews) were employed to fight the AI virus and to depopulate the farms. The costs will be covered by tax payers.

In Iowa, the Iowa Executive Council agreed to authorise a request from the State Department of Homeland Security and Emergency Management for up to 1 million US-$ to cover costs associated with the response to the avian influenza outbreak. Bill Northey, Iowa Secretary of Agriculture, estimated the costs of the outbreaks in Iowa at about $ 300 million, covering the direct losses of the killed birds, the costs for the depopulation, cleanup and disinfection of the affected farms and the disposal of dead birds (The Gazette (Des Moines) of June 29th, 2015).

In a meeting with the author in Des Moines (July 22nd, 2015), Dr. David Schmitt (State Veterinarian of Iowa) said that the direct losses might be considerably higher than the Secretary´s estimate as in total 24.8 million laying hens (42 % of the state´s inventory), 5.0 million pullets and 1 million turkeys had to be killed.

Decision Innovation Solutions, estimated the total cost to the economy of Iowa at $ 1.2 billion. This includes $ 800 million as direct losses in egg and turkey production and $ 400 million for wages and taxes. The economic research firm was asked by the Iowa Farm Bureau to calculate the cost of the AI outbreaks between April and June 2015. The firm also estimated that Iowa might lose about 8,500 jobs as a result of the 77 outbreaks (Decision Innovation Solutions, 2015a, p. 13). For the USA the company estimated an output loss of $ 2.6 billion and a loss of 15,693 jobs as well as a loss of value-added tax of $ 98s million (Decision Innovation Solutions 2015b, p. 3).

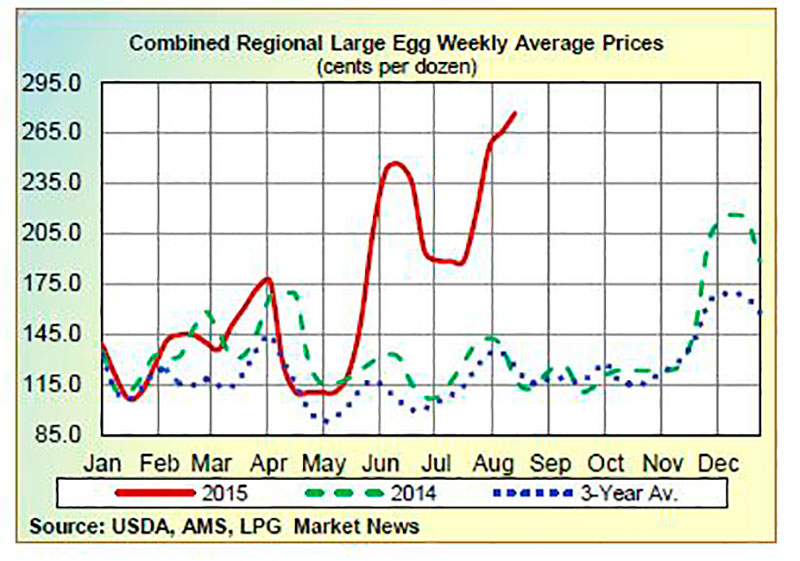

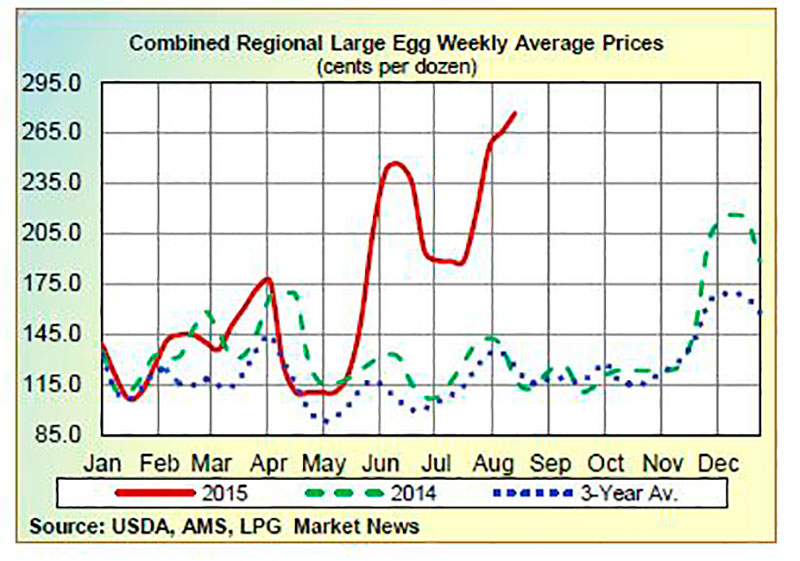

About 85 % of the infected and depopulated table egg laying hens were producing eggs for the egg processing industry, mainly in large inline operations. This resulted in severe economic problems for the leading companies (Michael Foods, Rembrandt Foods, and Sonstgard Foods). They were no longer able to fulfill their contracts with the food industry. One company declared force majeure hoping that this might be accepted by the food industry. The industry, however, argued that there were still sufficient eggs available on the domestic and the global market. Obviously, some egg processors began to purchase shell eggs for consumption for their processing plants, not only in the USA but also on the international market. This resulted in a dramatic increase of the retail price for shell eggs in the USA. In the first week of June, between $2.24 to $2.42 US dollar had to be paid for a dozen of large eggs, 60 % more than in the preceding week, but towards the end of June, prices decreased to $1.90 US-dollar per dozen again (see also figure 4) and remained fairly stable until mid-July. But then prices increased again because of the considerable reduction of the laying hen flocks and the constant demand for table eggs and eggs for further processing. In California more than $ 3 had to be paid for a dozen of large eggs according to a report of the Egg Industry Center (Iowa State University, Ames).

Figure 4. The development of shell egg for consumption prices in the USA (2013 – August 2015)

(Source: EGG-CITE Newsletter, August 19th, 2015)

The loss of 10.1 % of the average table egg layer inventory resulted in a shortage of egg products, in particular liquid egg products for the food industry. To reduce the shortage and to stop the rapid price increase (almost $ 10 per pound for dried whole egg powder and $ 2.10 per pound for liquid whole eggs) the food industry applied for an opening of the US market for foreign egg products. The Trade Department gave permission to five egg processing companies in the Netherlands to export to the USA. They already had a permission to export to the USA, but had not delivered products since 2012. This possibility had impacts on the egg trade between the Netherlands and Germany and the development of prices for processing eggs. Obviously, Dutch companies started to purchase eggs for processing in EU member countries. Increasing prices were the result. In the first week of June up to 80 cents/10 eggs were paid. Processing eggs were also exported to the USA from Germany for some weeks but did not reach high volumes and had only minor impacts on the price development for shell eggs for consumption.

The impact of the depopulation of the turkey farms on the availability of turkeys at Thanksgiving and on the price development are difficult to predict. As it will take some time until all farms can be repopulated, the losses in the production volume will accumulate over the next month. The estimated loss of 3.2 % of the annual U. S. turkey production, as estimated in the internal paper of APHIS, gives only a snapshot for the situation at a certain moment and may therefore be too low. This could indeed have impacts on the availability of turkeys and result in a price increase.

It has also to be considered that in contrast to laying hens, turkey breeder farms were severely affected. The loss of 360,000 breeder hens will cause a shortage of hatching eggs and poults, so that it will not be possible to repopulate all farms immediately after they have been cleaned, disinfected and tested. This will further reduce the production volume of turkey meat and result in additional financial losses for the farmers.

The AI outbreaks reached a loss of $ 390 million in export value in the first half of 2015 compared to 2014 according to a report of the USDA Poultry & Egg Export Council. Even though mainly turkey and laying hen farms were affected, the AI outbreaks also impacted the broiler industry. Because of the ban by the Russian Federation on poultry meat imports from the USA, the broiler industry had already reduced their chicken placements in early 2015. The banning of poultry products imports because of the AI outbreaks by about 30 countries further reduced the exports. The National Chicken Council estimated in a press release that the export volume in 2015 will be about 9 % lower than in 2014. In order to stabilise the situation, the USDA announced

(June 23rd) that it will buy leg quarters to stabilise the market and to stop the rapid price decrease. On the other hand, Brazil could profit from the situation. Several countries which imported leg quarters from the USA were looking for alternative sources of supply. CEPEA Brazil

(Centro de Estudos Avançados EM Economia Aplicada) announced that they were expecting the highest export volume for July 2015 with more than

400,000 t.

The banning of imports from the USA has already had and still has impacts on the breeding companies in the USA as they cannot export breeding stock, hatching eggs or one-day-old chickens to several countries. This has already led to a considerable interruption in the export of parent stock to non-American countries. The situation became even more serious for Hy-Line, the leading breeding company for laying hens, when an AI outbreak occurred in the United Kingdom in July which further reduced the export possibilities as Jonathan Cade (president of Hy-Line) declared in a meeting with the author in Des Moines (July 23rd, 2015). On the other hand, the import ban will cause a reduced egg and poultry meat production in countries that no longer permit imports from the USA. It is estimated that it will take at least six months, perhaps even longer, to stabilise the international markets and trade flows. This will happen, however, only under the condition that no new AI outbreaks occur in the fall of 2015.

Repopulation of affected farms

Before the affected layer farms can be restocked, several steps of cleaning, disinfection and testing have to be taken, as the State Veterinarian of Iowa, Dr. David Schmitt, explained to the author during the meeting on July 22nd. After cleaning and disinfection, the barns are heated up for at least three days to a temperature of 100 0F (= 37.8 0C), this phase is called the “baking phase”. After that, a sanitary phase of 21 days has to follow. Then numerous samples are taken in the farms. If the results of the PCR tests are negative, the restocking can begin. If the tests are positive, additional analyses have to be undertaken to identify the virus status and to decide if the virus material is still virulent. If this is the case, the whole procedure has to be repeated. Before restocking the farms, the one day old chicks are tested and then again after 21 days and then three times in seven days intervals. It is assumed that these tests are sufficient to detect an infection in an early stage even though only 5 birds per flock are tested. Prof. Dr. Hongwei Xin (director of the Egg Industry Center of the Iowa State University in Ames) argued, however, that the number of tested birds might be too low to really get a realistic idea about what was going on in a flock, as the statistical power of these tests was very low.

Perspectives

In a few turkey farms in Minnesota which were infected in early April, the placement of new flocks was permitted in week 25 (June 15th to 21st), knowing, however, that this might be a high risk as long as the outbreaks had not come to a complete end. Farmers were urging the state government to permit this step because of the high financial losses they had to foresee if they would not be able to participate in the most attractive market period for turkeys between Thanksgiving (November 26th) and Christmas. In Iowa, the repopulation of affected turkey farms was possible from mid-August on, as the State Veterinarian of Iowa declared, and if the necessary tests would show that no virulent viruses were left in the farms, the repopulation of layer farms could begin in early September. It is estimated that the egg industry in Iowa will need at least one year to recover from the loss of 42 % of its layer inventory.

In the meantime, State and Federal Offices are developing scenarios for the fall and early winter months of this year. The worst case scenario would be the southward migration of infected wild birds on all four flyways (Pacific, Central, Mississippi, and Atlantic) with a mutated AI virus. This would not only affect the leading states in turkey and egg production in the upper Midwest again but also the leading broiler producing states along the Atlantic coast (Delmarva Peninsula) to the Southeast in which about 90 % of the US broilers are raised. In such a case it might be necessary to combine stamping out methods and vaccination to protect the very valuable breeding stock in the eastern states of the USA. This would definitely have far reaching impacts on the exports of poultry products, especially broiler meat and breeding stock. In 2014, the USA and Brazil were the leading broiler meat exporting countries with an almost identical export volume of 3.5 to 3.6 million tons. An import ban by many countries would not only hit the US producers but also lead to a considerable shortage in several importing countries which are dependent on these imports. Despite the growing production capacity Brazil will not be able to compensate for the US export reduction.

Another challenge is the biosecurity problem on farm level. State and federal agencies are developing programmes, workshops and online brochures for the farmers to improve the biosecurity of their farms. The rapid dissemination of the AI virus in some counties in Minnesota and Iowa has shown that the farmers were not aware of their deficits and not informed about the risks connected with personal contacts, the use of equipment and the trucks which delivered the feed (see also APHIS: Epidemiologic and Other Analyses of HPAI-Affected Poultry Flocks).

Dr. John Clifford, Deputy Administrator Veterinary Services

(USDA APHIS), made this clear in a statement regarding biosecurity:

“Our investigation shows that the virus has been introduced into commercial poultry facilities from the environment (i.e., water, soil, animal feces, air) or from farm-to-farm transmission on human sources such as boots or equipment. After conducting an analysis of over 80 commercial poultry farms, APHIS cannot associate transmission of the disease with any single one of those factors, but it seems clear that lateral spread occurred when biosecurity measures that are sufficient in ordinary times were not sufficient in the face of such a large amount of virus in the environment.”

Dr. Sara McReynolds explained in the above-mentioned meeting with the author that even though only two commercial turkey farms were affected, their office was investing a lot of time and funds to improve the biosecurity on farm level. The affected farms were visited personally and checked regarding their biosecurity status. Based on these checks, suggestions were presented to the farmer to improve the biosecurity of his farm. Similar activities are also carried out in other states. Dr. David Schmitt, State Veterinarian of Iowa, made clear that his office would not be able to visit all poultry farms by staff members because of the high number of farms. He argued that initiatives to educate the poultry farmers regarding their biosecurity would have to be organised and financed by the integrators.

The long time needed to depopulate large layer farms has led to considerations during a webinar organized by United Egg Producers (August 19th) to shut down the ventilation systems as an emergency method in affected farms to reduce the risk that the virus is going into fans and exhausted into the atmosphere. This method should only be used, however, in a worst-case scenario or when all other euthanasia options had been exhausted, declared Chad Gregory, president of UEP. He also stated that a lot of research would be necessary to decide if additional gas should be applied and how long it would take for the birds to die (WATTAGNet August 20th 2015).

A special problem could arise in the barns for broiler growing in the Southeast (so-called Louisiana barns). Because of the open sides with curtains it will be almost impossible to close them completely against the environment. In addition, many of the broiler houses are relatively old and do not meet the necessary standards of a high biosecurity level. With only four to five months remaining in July and August 2015 to improve the situation, this might become the weakest point regarding the prevention of another introduction of a highly pathogenic virus strain into the US poultry industry.

Acknowledgement

I want to thank Dr. Fidelis Hegni (USDA APHIS) for reading the manuscript and his comments as well for his correction of data.

References

Decision Innovation Solutions: Economic Impact of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) on Poultry in Iowa. Urbandale, Iowa 2015a.

Decision Innovation Solutions: Economic Impact of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) on Layers in the U. S. Urbandale, Iowa 2015b.

http://www.CHICK-SITE.com

http://www.EGG-CITE.com

httpy://thepoultrysite.com

http://www.wattagnet.com

http://www.aphis.usda.gov

USDA APHIS (ed.): Epidemiologic and Other Analyses of HPAI-Affected Poultry Flocks. Washington, DC. July 15th, 2015.

USDA APHIS (ed.): Carcass Management during a Mass Animal Health Emergency. Washington, D. C., August 2015.

Linkedin

Linkedin